“The Art Books of Henri Matisse” is a lively and timely exhibition at the Portland Museum of Art featuring scores of prints from four of Matisse’s dozen or so book projects.

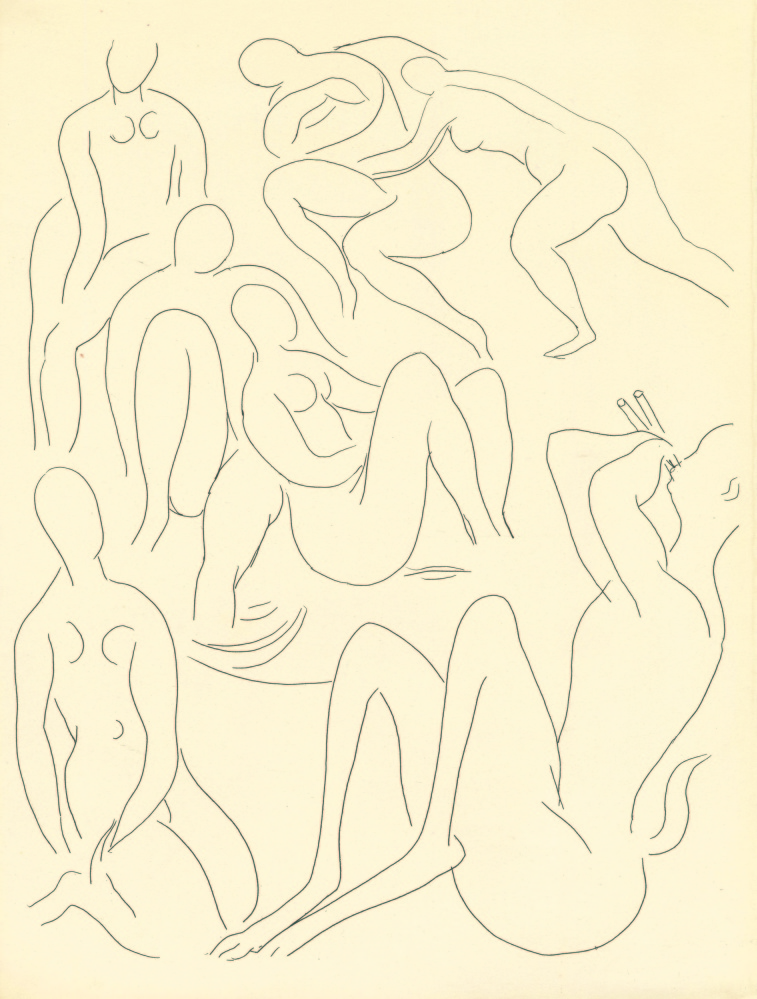

Matisse’s book images range from simple line drawings and decorative elements to some of his best known works from any era, in particular the colorful paper cutout compositions from his 1947 graphic masterpiece “Jazz.” While Matisse’s power as a painter is most immediately obvious through our visceral response to his color, his graphic work features his subtle virtuosity with line. Unlike many of his peers, Matisse tended to use line best as outline which we see as boundaries between positive forms and negative space. To think of this as objects and their outlines, however, is to underestimate the artist.

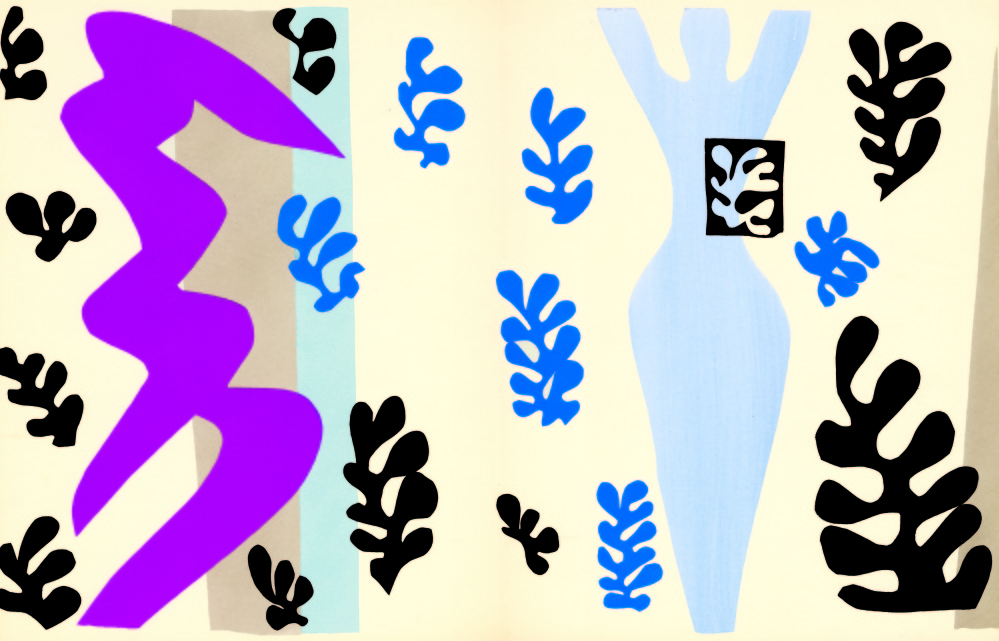

Matisse set forms to ebb and flow between positive and negative space. In “Destiny” from “Jazz,” for example, we see this toggling between interlocked pink and black forms as the primary content of the image. Instead of playing the historically common role of art as a linear narrative to be properly unfurled toward a singular understanding, this kind of work puts its internal systems logic to bear as a function of the viewer’s real time perception. In other words, Matisse often needs you – the viewer – to bring his works to life. And no one has ever been better than Matisse at achieving such an accessibly delicious here-and-now experience.

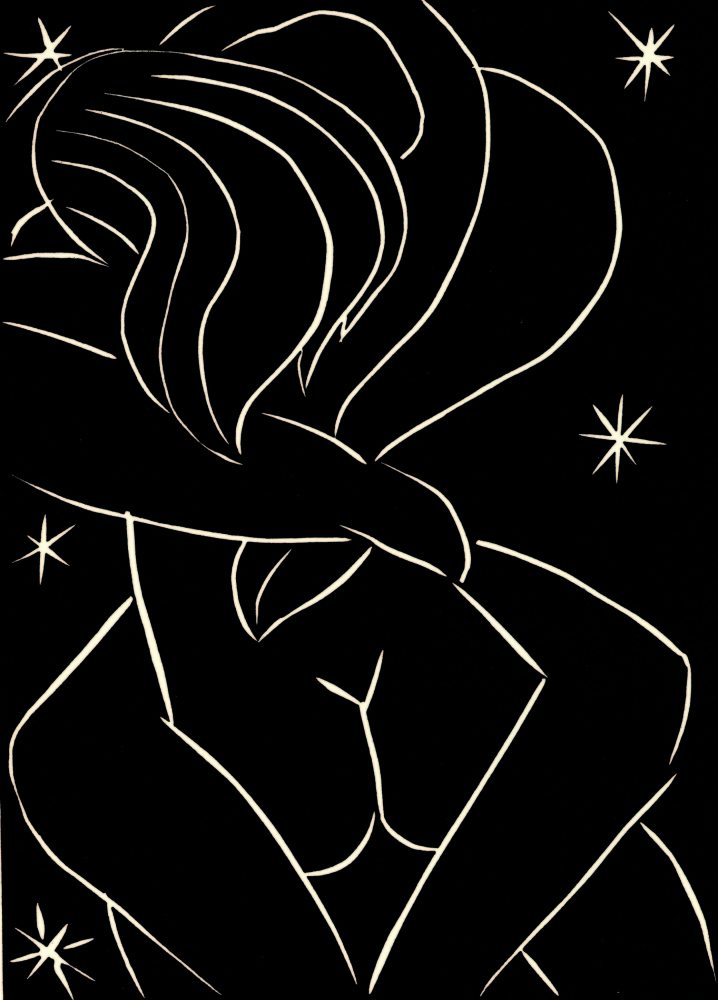

“Pasiphaë, Song of Minos (The Cretans)” is the 1943 retelling by Henri de Montherlant of the Greek myth in which Poseidon cursed Pasiphaë, the wife of the insufficiently-sacrificing King Minos, to mad desire for a bull, resulting, nine months later, in the Minotaur. It’s a disturbing tale caught between the dirty Surrealist age and simmering wartime anger (Matisse’s beloved daughter was tortured by the Nazis). Matisse, however, outstrips Montherlant in terms of beauty, anguish, tenderness of form, passion and compassion. Matisse’s images are reverse lino cuts (light image, dark backgrounds) sometimes made with a single stroke of genius – quite literally, for example, in the case of “Anguish.”

The standard story of the 20th century’s top two painters says that Picasso was the drawing guy and Matisse was the painter – rather like Ingres and Delacroix. Matisse, however, more than makes his own case for line throughout “The Art Books of Henri Matisse,” but particularly with “The Poetry of Stéphane Mallarmé.” Matisse’s lines flow with the idyllic vitality of spirit for which Mallarmé pines so eloquently in his frustrated ennui.

Matisse’s least interesting works were made for Poèmes featuring the late-medieval texts of troubadour Charles d’Orléans (1394-1465). Matisse gives us fleur-de-lys after fleur-de-lys scribbled quickly in crayon like bored afterthoughts on kids menus.

“Jazz” was published in 1947, six years after Matisse (1869-1954) was diagnosed with abdominal cancer. After surgeries that left him unable to paint or sculpt, Matisse took up scissors and paper to create some of the most influential and beloved works of the 20th century. Behind their popularity, however, are boundary-shattering qualities. Matisse worked with paper painted with the same gouache used to make the book using stencils. In other words, these can rightly be seen as paintings, drawings, graphic works or even collage – except for the fact that Matisse pinned instead of glued his paper elements so that he could keep adjusting them. “Collage” means “glued” and it is hardly ironic that Matisse would have an attitude about the technique, considering it was invented by his arch rival’s (Picasso) partner in Cubism, Georges Braque. While this might seem little more than chuckle-worthy pretend-drama, it’s a serious point. Matisse’s cut-outs and Cubist collage, after all, comprise two of the most influential moments of painterly modernism, and both pointed away from traditional painting toward mass culture and post-modernism.

The fundamental truth about Matisse is an oxymoron: Among leading artists of the last century, his work is the most accessible while being among the least explainable. It is visually indulgent, saturated and satisfying. It defies our ability to describe its success because it arrives as subtleties on waves of apparent simplicity. It makes us not want to question why we like it as much as we do, so Matisse is able to slip the brilliance of his content in through the back door, beyond the reach of our critical faculties. And this was by design: It’s what Matisse meant when he famously (and rather controversially) said he wanted his art to be “a soothing, calming influence on the mind, something like a good armchair which provides relaxation from physical fatigue.”

“Jazz” is, in fact, a trip to the circus. It features clowns, knife throwers, sword swallowers and trapeze artists, and even what we can assume was Matisse’s intended frontispiece featuring the word “Cirque” – circus. The title “Jazz” was a gesture of the publisher. It was not only a savvy marketing gesture, it more fairly captures Matisse’s artistic content: It is not posed, contrived and well-rehearsed sleight of hand, rather, the work is improvised, loose, bold and yet immeasurably nuanced. It contains a few crafty undercurrents, like the doubled “Wolf” which is commonly taken as reference to Hitler. Some of Matisse’s most beloved images are from “Jazz,” like the dancy dot-hearted “Icarus” and the celebratory swag-hearty “The Horse, the Rider, and the Clown.”

“Jazz” is arguably the art book masterpiece of the 20th century. And it’s an argument worth having: You can see this and, an hour and a half later, Picasso’s Vollard Suite now on view at Colby College. But this conversation also looks to today. Then, new technologies like color magazines and intercontinental airmail were changing the public’s – and artists’ – relation to graphic arts. Now, with digital photography, digital printing and the internet, we are again facing a complete rebuild of our understanding of graphic arts and imaging. “The Art Books of Henri Matisse” is a reminder that, while Matisse’s work is easy to digest, it should never be underestimated.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at dankany@gmail.com.

Send questions/comments to the editors.