Personal bankruptcy filings in Maine have been declining steadily since 2010, but attorneys and consumer advocates say the drop-off in bankruptcies isn’t necessarily good news.

In fact, it might be an indicator that Mainers’ financial situations have worsened overall, they said, a reflection of increasingly squeezed households that can’t afford to file for bankruptcy, or people who have serious student debt that isn’t resolved through filing.

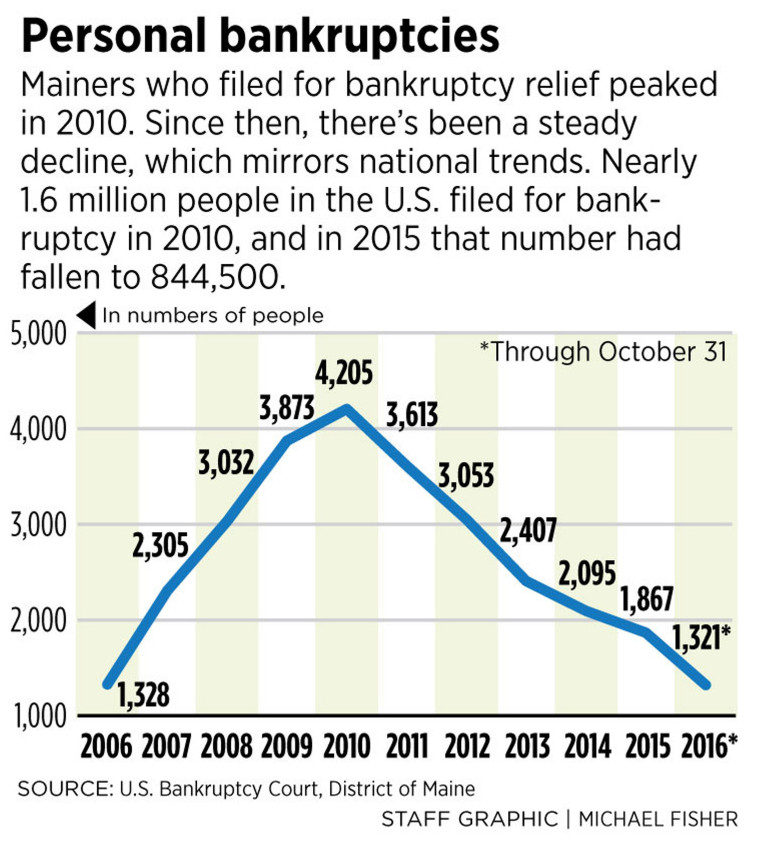

Maine bankruptcy filings reached their most recent peak of about 4,200 in 2010, according to the U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the District of Maine. Since then, bankruptcies in the state have declined steadily each year to fewer than 1,900 in 2015. As of Oct. 31, just over 1,300 Maine bankruptcies had been filed in 2016. The pattern mirrors a national trend of declining bankruptcy filings, which have been falling between 10 percent and 13 percent year-over-year since the 2010 peak.

Bankruptcy specialists in Maine agree that there is no simple explanation for the sharp drop-off in filings. Although low unemployment and more people with health insurance are likely factors, the decline in filings is not just a matter of post-recession economic recovery, they said.

“Historically, when the economy is improving, people tend to file for bankruptcy more rapidly,” said Peter Fessenden, the U.S. Bankruptcy Court’s Standing Chapter 13 Trustee in Maine.

A 2006 study by the U.S. Federal Reserve of St. Louis bears this out. It found that bankruptcies can increase during periods of economic growth “as people become more confident in the future and are willing to take on a greater debt burden and finance their increasing obligations based on current income.”

So what’s different about this economic recovery that has caused bankruptcies to decrease so significantly? There are no concrete answers, only theories.

WHY PEOPLE FILE FOR BANKRUPTCY

Before attempting to understand the current decline in filings, it’s important to understand why people file for bankruptcy.

In the vast majority of cases, the road to bankruptcy is triggered by an event that dramatically changes the filer’s financial situation for the worse. The Federal Reserve refers to it as an “unexpected insolvency event.” Such events can include divorce, job loss, the death of a spouse, or a major medical expense that is not covered by insurance.

Still, most people don’t just run straight to their nearest bankruptcy court when such an event occurs. Usually, they try to weather the new financial situation for an extended period before ultimately turning to bankruptcy out of frustration, despair or anxiety.

“People file for bankruptcy because they can’t take it anymore,” Fessenden said.

The Federal Reserve found that the typical person who files for bankruptcy is a “blue-collar, high school graduate who heads a lower middle-income class household and who makes heavy use of credit.” In other words, a person who is in a financial position to obtain credit, but not in a financial position to overcome an unexpected insolvency event.

Job loss is of particular concern to Fessenden, an attorney whose job is to assist debtors in Maine and their attorneys with compliance and other issues when they file for Chapter 13 bankruptcy. A Chapter 13 bankruptcy involves putting the debtor on a three- to five-year plan to reorganize their debt and pay off priority creditors. It differs from a Chapter 7 bankruptcy, in which the debtor liquidates all nonessential assets to pay off priority creditors but does not engage in a reorganization plan.

Fessenden said that in an age when finding a new job often involves relocating, many Mainers can’t afford to sell their homes and move because they are locked into mortgages that exceed the value of their homes. Home prices have been slow to recover from the recession: October’s median home sale price of $192,500 was still below the 2006 median of $192,519. Fessenden refers to such homes as “zombie properties.”

The only option for residents of zombie properties may be to declare bankruptcy if their financial situation becomes too dire, he said.

“There’s going to be this wave of Chapter 7 filings,” Fessenden predicted.

A COSTLY SOLUTION

Another factor contributing to low bankruptcy filings is likely the expense. People who are struggling financially simply can’t afford the costs associated with it, said John Rao, an attorney at the National Consumer Law Center in Boston, noting that a lot of people probably should be filing for bankruptcy, but aren’t.

In 2005, Congress passed the Bankruptcy Abuse Prevention and Consumer Protection Act, which is designed to make it more difficult for consumers to file for Chapter 7 bankruptcy. Chapter 7 is by far the most common form of personal bankruptcy in Maine and nationwide.

“As a result of the 2005 amendment, costs increased dramatically,” said Lois R. Lupica, Maine Law Foundation professor of law at the University of Maine School of Law. “There was a whole swath of the population that couldn’t afford to file.”

Fessenden said Maine is one of the most expensive states in which to file for bankruptcy, and the legal costs can climb as high as $8,000 for a typical case.

Bankruptcy attorney James Molleur of Molleur Law Office in Augusta said he doesn’t believe that filing bankruptcy in Maine is particularly more expensive than in other states, but he agreed that many Mainers can’t afford to file since the 2005 law made the legal process far more complex.

“People are so financially strapped that it’s a question of whether they buy groceries, or pay the rent, or file for bankruptcy,” he said.

Molleur acknowledged that bankruptcy carries a social stigma, and that it is important for people to honor their debts whenever possible. Still, he said, bankruptcy is a necessary “release valve” for those with no foreseeable means of repaying what they owe.

Molleur said he is hopeful that with the presidential election of Donald Trump, a businessman who has been involved in several bankruptcies, the stigma will diminish and it will become easier and less expensive to file for bankruptcy.

“I think Trump will be more practical about dealing with debt issues,” he said.

The attorneys said Mainers who are struggling financially because of heavy student loan debt also would be less likely to file, because most student debt cannot be discharged through bankruptcy.

“It’s possible that bankruptcy just doesn’t offer the remedy that people need,” Lupica said.

Alec Leddy, clerk of the U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the District of Maine, agreed, saying “filings would skyrocket” if the law were changed to allow student debt to be discharged easily through bankruptcy. Mainers who graduate from college have an average debt of nearly $30,000, according to federal data.

“Student debt is way up, but that’s not very helpful, because you can’t get rid of it in bankruptcy,” he said.

UNEMPLOYMENT RATE A BRIGHT SPOT

A few of the theories to explain the decline in bankruptcies suggest that Mainers’ financial situations have improved in some ways since bankruptcies spiked in 2010.

For one thing, a lot more Mainers have jobs. Leddy noted that the state’s current unemployment rate of 4 percent is about half what it was in 2010, adding that high unemployment correlates directly with increased bankruptcy filings.

“I think the unemployment rate has a lot to do with it,” he said.

Lupica said it’s also possible that fewer Mainers are getting hit with massive hospital bills – a leading reason for bankruptcy filings – because more people have health insurance now under the Affordable Care Act.

Home foreclosures are down considerably from 2010, and lenders are far less inclined to issue personal, mortgage or business loans to those with a relatively high risk of default, the attorneys said.

Fessenden said consumers’ attitudes about borrowing also have changed, to some extent, because of the 2008 financial crisis. “People are comfortable getting into debt, but they’re not comfortable getting into too much debt,” he said. “I think people are still using their credit cards, but I think they are using them less.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.