Maine’s corrections commissioner will convene a panel of outside groups to scrutinize department policy in the wake of a suicide by a transgender teenager at Long Creek Youth Development Center, the first death in at least 20 years at the state’s premier youth correctional facility, the commissioner said Tuesday.

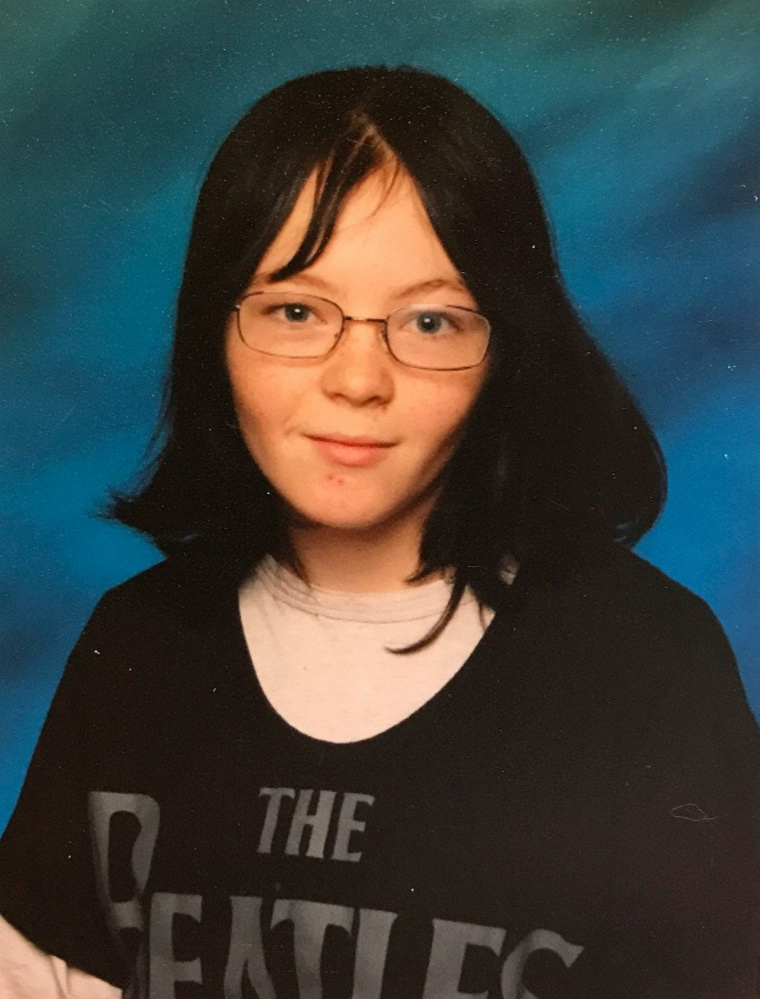

Joseph Fitzpatrick said he also has issued temporary policy directives following the death at the South Portland facility of Charles Maisie Knowles, a 16-year-old transgender boy who was being held there on a felony arson charge. Knowles, who hung himself Oct. 29 and died Nov. 1, had been on and off suicide watch several times, his mother, Michelle Knowles, said.

The interview is the first Fitzpatrick has granted since the death more than three weeks ago. He said he was motivated to speak out because he had become exasperated and frustrated with the tenor of media coverage, including from national experts who were critical of the department but who have no experience with Long Creek.

“I got to the point where I couldn’t look my staff in the eye anymore,” he said in a telephone interview. “I couldn’t read what I was reading and watch what I was watching on the news and not say anything.”

Although Fitzpatrick declined to identify what policy changes he has made and precisely which outside advocacy groups he will invite to the table when they meet next week, he said the review will include input from national and local experts from the worlds of psychiatric care, corrections, disability rights, civil rights, LGBTQ rights and others. No topic will be off the table, he said.

Fitzpatrick also rebutted the central criticism leveled at Long Creek by Michelle Knowles, who insists that multiple staffers there told her that they could not provide more comprehensive mental health counseling because Maisie was a detainee and had not been committed by a judge long-term.

But Fitzpatrick said that is not true.

“There is no differential between committed and detained in terms of health care or mental health care,” he said. “In terms of access to psychiatry and medication and clinical social workers and psychologists, it’s the same. We start with an assessment across the board, whether you’re committed or detained, and based on that assessment we provide a level of treatment that’s needed.”

Fitzpatrick said about 169 state employees are responsible for the welfare of 69 committed residents and 12 detainees at Long Creek. None of the current residents identifies as transgender, he said.

All medical services – including psychiatric care – are provided by an outside contractor, Correct Care Solutions, an international company based in Tennessee that provides healthcare in 38 states across a range of correctional, civil and institutional settings. A staff of about 10-12 CCS employees, along with one state-funded clinical social worker, provide all assessment and treatment needs presented by residents, he said.

The private contract with CCS for medical care spans all state-run correctional facilities, and has been in place for about four years, Fitzpatrick said.

He also dismissed any suggestion that a private for-profit company such as CCS would have an incentive to provide less costly, substandard health services to Maine people who are detained or incarcerated.

“I’ve been with the department 24 years. I’ve seen those providers, I’ve seen those companies. I’ve seen people in the past who are more concerned with cost containment than quality of care,” he said. “Correct Care Solutions is not that at all. We’ve been extremely pleased with the quality of care.”

But Michelle Knowles has said practices at the facility were different.

She said that because her son – who was biologically female but identified as male from age 3 – was being detained pretrial and had not been committed to Long Creek by a judge, he was unable to access a level of care that more permanent residents may receive.

Instead, medical staff planned to focus on the “day to day” issues that confronted Maisie, who had an extensive and well-documented history of mental illness.

“They absolutely could not (provide more care) because my child was a detainee, that’s the difference,” Michelle Knowles said Tuesday. “I was told that multiple times. That is very clear for me, there is no question about that. That’s what frustrated me.”

Only after an outside physician who had previously been caring for Maisie intervened did Long Creek staff acquiesce to providing more extensive, comprehensive mental health treatment, Knowles said. But the decision to move forward with more care was too late, she said. A day after Knowles learned of that decision, Maisie was being rushed to a Portland hospital.

Experts contacted by the Press Herald/Maine Sunday Telegram said that although Long Creek’s mission is as a correctional facility and not a mental health care facility or hospital, its staff has an obligation to provide all necessary health care required by anyone in their custody, regardless of their detention status, and that anything less would be a drastic departure from national standards.

Fitzpatrick said those news reports and others contained inaccuracies, but he could not identify what they were without breaching confidentiality laws and compromising the two investigations that remain open by the state Attorney General’s Office and the Maine State Police.

Until those investigations conclude, it will be impossible to say precisely what care Maisie received, how frequently it was administered, and what staff did to prevent and then respond to her suicide attempt.

Send questions/comments to the editors.