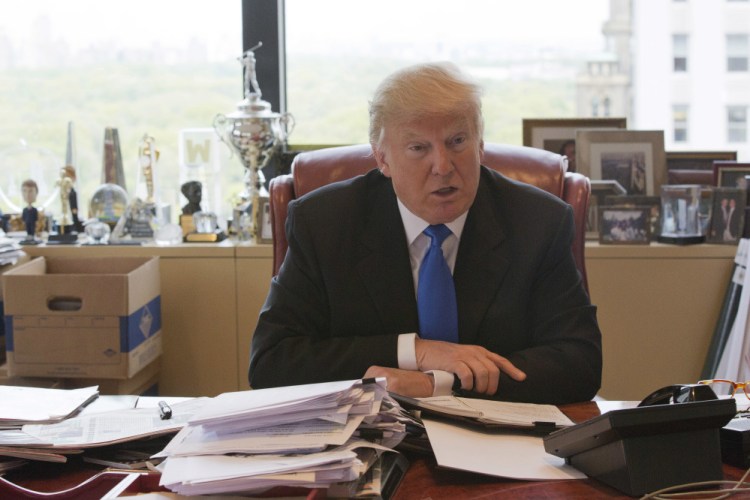

Donald Trump’s stunning victory will force the United States to confront a series of never-before-seen entanglements over the president’s private business, debts and rocky financial history.

No laws prohibit Trump from involving himself in his private company, the Trump Organization, while serving in the highest public office.

And Trump has so far resisted the long-standing presidential tradition of giving his holdings to an independent manager, stoking worries of conflicts of interests over his businesses’ many financial and foreign ties.

Trump’s business empire of hotels, golf courses and licensing deals in the U.S. and abroad, some of which have benefited from tax breaks or government subsidies, represents an ethical minefield for a commander-in-chief who would oversee the U.S. budget and foreign relations, some analysts say.

Trump’s companies are partially indebted to banks in Germany and China. On financial disclosure filings, Trump listed involvements in more than 500 companies, some in countries where the U.S. has sensitive diplomatic or financial relationships, such as Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and China.

Those entanglements are unprecedented, unavoidable and “troubling,” said Ken Gross, a former elections enforcement official and lawyer who has advised presidential candidates from both parties, after the election. “He has investments in businesses in unfriendly countries and the businesses are often tied to those unfriendly governments.”

“The obvious solution is to sell those interests,” Gross said, but many holdings may not be easily sold, or are still tied to debts personally guaranteed by Trump. “Removing himself or his family from the perception of self or family interest may prove difficult,” he added.

Ethics officials urged Trump during his campaign to pledge he would sell his businesses or cede them to an independent authority. Many modern presidents – including Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton and both Bushes – went beyond what was required and placed their assets in “blind trusts,” run by independent trustees who keep complete control.

But Trump has refused to make such a pledge, saying only that he would give companies to his children and executives to run. Attorneys said that would put little distance between a President Trump and the businesses he spent a lifetime grooming and profiting from.

“It’s silly to suggest there’s any avoidance of conflict by having your family run the interests. He talks to his family all the time,” said Trevor Potter, a former Federal Election Commission chairman and general counsel for George H.W. Bush and Sen. John McCain, R-Ariz., in September.

It’s “unthinkable in recent history,” Potter added, that “there’s the possibility of a president being able to affect his own personal financial interests, conceivably to the detriment of the general public.”

Members of Congress must recuse themselves from government dealings touching on their own financial interests, according to strict regulations in the Ethics in Government Act of 1978, enacted after Watergate. Presidents, however, were made exempt from those rules on the belief they could further complicate the wide-ranging job.

In the run-up to the election, Trump said he would take little interest in his businesses if he won the Oval Office. “If I become president, I couldn’t care less about my company. It’s peanuts,” he said during a January debate. “Run the company, kids. Have a good time.”

The Trump Organization’s executive vice president, Alan Garten, echoed that sentiment to The Post in September. “His focus is going to be solely on improving the country,” Garten said. “The business is not going to be a factor or an interest at that point.”

Trump’s son Donald Trump Jr. has insisted that Trump’s holdings would go into a blind trust managed by him and his siblings Eric and Ivanka Trump.

“We’re not going to be involved in government,” Trump Jr. said in September on “Good Morning America.” “He wants nothing to do with the company. He wants to fix this country.”

When pressed over the potential of Trump and his family still discussing the business while Trump is in office, Trump Jr. said, “We’re not going to discuss those things. . . . Trust me. As you know, it’s a very full-time job. He doesn’t need to worry about the business. The business is in good hands. He trusts us with that, 100 percent.”

Trump’s campaign funneled vast sums of money to private Trump companies, and he has voiced interest in his companies reaping benefits of his rise to public power. In June, he tweeted about Trump University, the real-estate seminar program now in a federal civil fraud trial, “After the litigation is disposed of and the case won, I have instructed my execs to open Trump U(?), so much interest in it! I will be pres.”

During his victory speech early Wednesday, Trump took pride in his business record and connected it to his ability to lead the country, saying, “I’ve spent my entire life in business, looking at the untapped potential in projects and in people all over the world.”

Trump business and campaign officials did not immediately respond to requests for comment on any timeline or details for the next steps Trump would take with his business empire.

Trump’s company oversees eight U.S. hotels in Chicago, Honolulu, New York City, Las Vegas, and its newest, in Washington, opened a few blocks from the White House on the likely route of Trump’s inauguration parade.

At the new Trump International Hotel in Washington’s Old Post Office Pavilion, which his company leases from the federal government, Trump now effectively serves as both the landlord and the tenant. It’s unclear how talks over lease payments or building maintenance would be conducted.

The Trump Organization is also set to receive federal tax credits to preserve the project’s historic nature – a program his administration will now oversee. Trump has an estimated $42 million of his own company’s money in the project.

Similar situations could emerge as federal housing officials – future employees of President Trump – will now be charged with enforcing housing rules, including at Trump properties in New York City, Chicago and elsewhere.

Free speech advocates have decried deals federal officials made providing the Trump Organization control over parts of Pennsylvania Avenue around the hotel. President Trump is poised to oversee those agreements with his company as well.

Trump real-estate holdings and other companies owe hundreds of millions of dollars to domestic and foreign banks, which ethics advisers say is a wide vulnerability for Trump that could tilt his judgment or independence. At one Manhattan office tower co-owned by Trump, the lenders include the Bank of China, a massive lender in the Asian superpower Trump has repeatedly attacked.

The full extent of Trump’s business relationships around the world remains unknown. He has refused to release his tax returns, which would outline key information about his financial holdings and foreign accounts.

The biggest lender to Trump’s business empire is Deutsche Bank, the German financial giant now negotiating a settlement with the U.S. Department of Justice to settle claims related to disastrous “toxic” mortgages the bank issued amid the housing crisis.

Justice officials said in September they would seek a $14 billion fine from the bank, a vast sum that sparked worries over the bank’s financial survival. But the final fine has not been publicly made official, and government-ethics experts have voiced concern that a President Trump could potentially influence the negotiations.

Garten, the Trump company executive, told The Post in September that he did “not see the conflict” in Trump taking control of a government pushing to penalize one of Trump’s most important financial allies.

The bank has undergone criminal investigations by government authorities in the U.S. and other countries. After one probe last year, the bank agreed to pay $2.5 billion in fines to resolve a scandal over its alleged rigging of influential loan interest rates.

In June, the International Monetary Fund said the bank was one of the biggest “contributors to systemic risks in the global banking system.”

Trump’s companies signed for roughly $360 million in Deutsche loans tied to the Trump National Doral golf club in south Florida, the Trump International Hotel and Tower in Chicago, and the new Trump International Hotel in Washington. Those loans are set to come due by 2024, which could parallel the end of a possible Trump presidency’s second term.

Since 1998, Deutsche has been a lender or co-lender in at least $2.5 billion in loans to Trump or his companies, a Wall Street Journal analysis found in March.

Trump’s election will again spotlight the many connections between his businesses and Russia, a long-standing antagonist of the United States. Trump has praised Russian President Vladimir Putin and voiced hopes he could develop new real-estate businesses there.

Strong evidence suggests Trump’s businesses have received significant funding from Russian investors. Donald Trump Jr. said at a New York real estate conference in 2008 that “Russians make up a pretty disproportionate cross-section of a lot of our assets,” and that “we see a lot of money pouring in from Russia.”

The election of Trump, who campaigned against trade and immigration, sent shock waves through financial markets across the world. Global stocks and the dollar plunged and, though some markets have recovered early losses, analysts have pointed to growing uncertainty among companies with foreign dealings.

“The U.S. economy and financial markets suddenly find themselves in no man’s land,” said Mark Hamrick, Bankrate.com’s senior economic analyst. “The way forward for large companies, for example, doing business across borders, as well as any size firm reliant upon an immigrant workforce, is difficult to chart from here.”

How Trump’s company could evolve remains a mystery. The election has transformed Trump from a noted real-estate developer and reality-show host into one of the world’s most famous men, with a fan base energized by his rhetoric and showmanship and, perhaps, willing to follow him beyond the vote.

But his most energized audience – of, largely, middle-American and blue-collar voters – is also a class his businesses have long ignored, through high-class offerings such as $800 hotel rooms and $30,000 golf-club memberships.

“He’s built this enormously resonant brand with what I’ll affectionately call angry white males. It’s not only a big market, but it appears to be growing,” said Scott Galloway, a professor of marketing who teaches brand strategy at New York University, on Tuesday. “But his current product offering caters to affluent, fortunate and relatively happy people. And as a general rule, the affluent are mildly horrified by the current trajectory of the Trump brand.”

Trump’s brand may remain anathema to some potential customers who were turned off by his campaign despite his victory.

Trump International Hotel and Tower, a 57-story tower that opened in Toronto four years ago, was placed into receivership recently when it failed to hit financial projections, according to court filings. Trump operates that property but does not own it. However, Symon Zucker, an attorney for the project’s owner, said Tuesday that a Trump victory wasn’t “going to affect it positively.”

“All the same people who weren’t going to come to it before aren’t going to come to it now,” he said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.