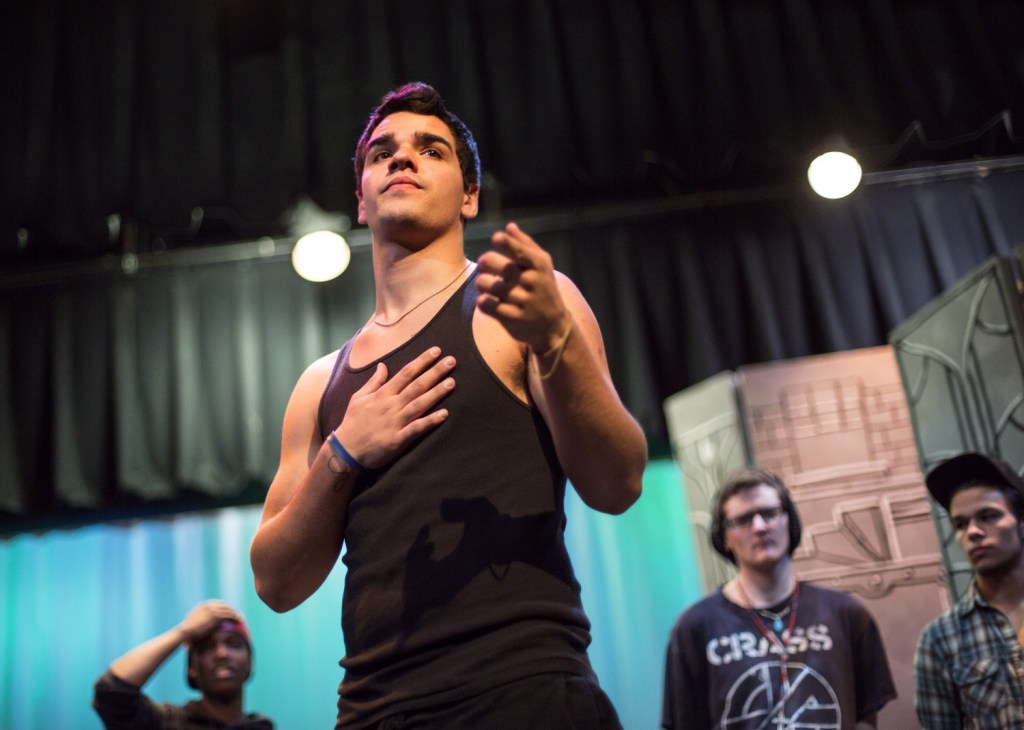

STANDISH — Cullen Dumbrocyo’s voice wavered as he stood onstage at his old high school, in front of a couple of hundred students, and asked for their forgiveness.

The 20-year-old from Standish was arrested in May after he and two other young men broke into Bonny Eagle High School, smashed a vending machine, sprayed fire extinguishers and dumped food onto floors. More than $6,000 in damage was done, and Dumbrocyo spent nearly three months in the Cumberland County Jail.

He vandalized the school just a few months after he had finished serving four years in a juvenile correctional facility for his role in burning down the historic Richville Chapel in Standish.

He asked the teens in the audience, just a few years his junior, to see him for who he is now, not who he was or what he’s done.

“I am sorry for what I’ve done; I’m doing better things now,” he said. “I want people to learn from my story, so they don’t have to go down the same path I went down.”

Dumbrocyo found the courage and the desire to apologize with the help of Maine Inside Out, a theater program for current and former juvenile inmates. Members express themselves through theater, find support in their efforts to change, and take ownership of what they did and who they want to be. The group’s three founders and co-directors have an overall goal of using the nine-year-old program to change people’s attitudes about incarcerating youth in prison-like settings, and ultimately dismantling the system.

FROM POWERLESS TO FINDING HOPE

Dumbrocyo’s apology, which was a condition of his release from jail, came just before he and about a dozen members of Maine Inside Out performed Thursday at Bonny Eagle.

The group, all recently released, performed a theater piece called “Do You See Me? All Who Struggle, Salute.” It was an abbreviated version of a piece the group will perform Thursday at the University of Southern Maine’s Hannaford Hall in Portland with 40 or more group members, including some currently held at Long Creek Youth Development Center in South Portland.

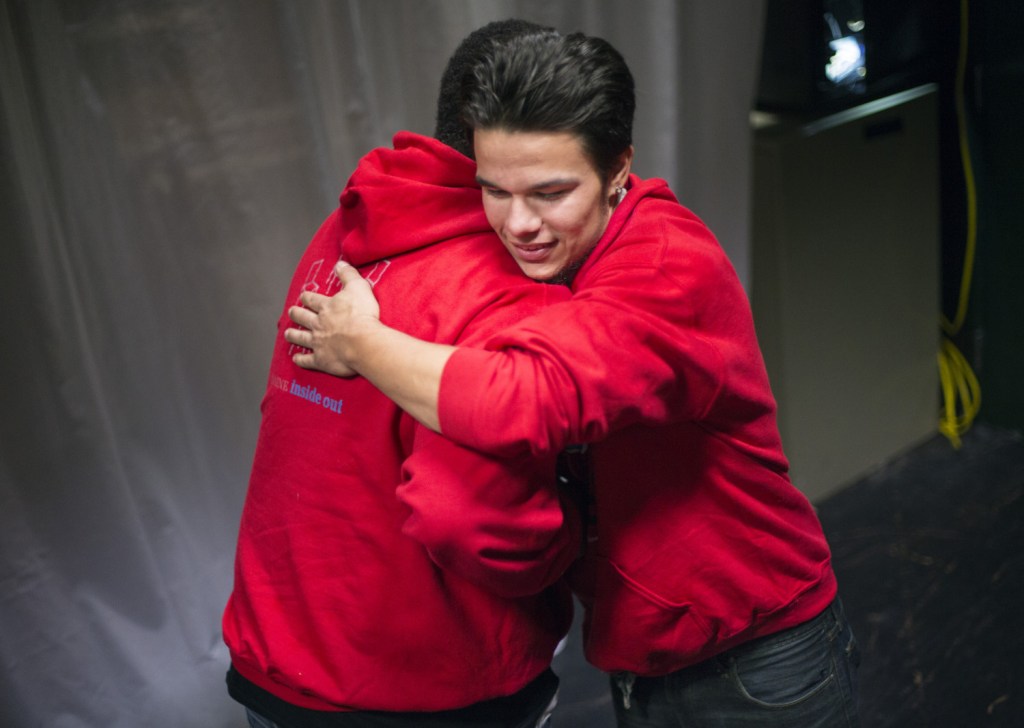

The figurative piece began with the members marching onto the stage, wearing red hooded sweatshirts, stomping and clapping rhythmically. One of them, portraying an authority figure, shouted “Freeze” and “All who struggle, salute.” The 15-minute performance included dialogue that dealt with racism, police brutality and the members’ wishes to be judged on who they are, now. The phrase “Do you see me?” was repeated often.

The vignettes and dialogue were created by the members, who used no written script. Skye Gosselin of Biddeford, 18, sang a few lines of a song she wrote: “People see what they want to; They don’t understand me; Trying to let my voice out; Gotta break the wall and set it free; I just want you to know, this isn’t who I want to be.”

The members of Maine Inside Out range from people like Dumbrocyo who spent much of their teenage years locked up, to those like Gosselin, who spent about 30 days in Long Creek when she was 14 for truancy and fighting, as well as a couple of days in the York County Jail for a probation violation. Gosselin, feeling empowered by the group, will attend Southern Maine Community College next year and hopes eventually to work in the legal field, helping in the defense of juveniles.

“I have a lot of background in the legal system, watching it. I’m outspoken and I’m smart, so I think I could help people,” Gosselin said.

Most members talk about how captivity made them feel powerless and hopeless, and Maine Inside Out has helped them find hope. They feel like they are finally doing something constructive, both by helping one another and by trying to change attitudes about jailing young people.

They say Maine Inside Out has helped them begin to feel like they matter.

“When I first got involved (with Maine Inside Out) they told me (to) take your experiences and put them in a play. That’s what I did. So now I feel like by telling my story, by doing what we do, we might make a difference,” said Dumbrocyo. “I’m not just someone walking around; I’m doing something to help.”

OWNING UP TO ‘A BAD MISTAKE’

Looking back on the days before he was first jailed at Long Creek, Dumbrocyo said he was picked on a lot as a kid. That led to anger and a search for emotional escape. He smoked a lot of pot and made some “stupid decisions.”

One of those was in 2012, when he and another boy set fire to the 114-year-old Richville Chapel, a small church with a congregation of about 20 off Route 114 in Standish. The building was destroyed, with only one wall left standing.

He says he’s still not sure why he vandalized his old school just a few months after completing his four years at Long Creek. He was angry about an ex-girlfriend, he said, and had started hanging around with the same young man who was part of the church burning four years earlier.

“I made a bad mistake, a stupid decision, and I’m still trying to figure that one out,” said Dumbrocyo. “That’s part of why I think Maine Inside Out will help me, the weekly check-ins. I feel like whenever something’s bringing me down, I know I can talk to someone.”

Even though Dumbrocyo had been involved with Maine Inside Out while in Long Creek and enjoyed it, he didn’t stay active when he first got released.

“I wasn’t going (to Maine Inside Out sessions) at all when that happened,” Dumbrocyo said of the school vandalism.

One of the major problems faced by young people getting out of a correctional facility is finding help with their transition, said Tessy Seward, a co-director of Maine Inside Out. Young people who live in rural areas might not have access to phones or transportation. So getting to one of Maine Inside Out’s weekly meetings might not be easy. Even calling another member to share feelings might require borrowing someone else’s phone.

“That’s one of the reasons we started this, to help them get peer support in a culture of respect,” Seward said. “We feel like connectedness, getting empathy and compassion, is the biggest influence on someone’s choices. I don’t think that kids change to the straight and narrow because they’re afraid of punishment.”

DOZENS INVOLVED IN THE PROGRAM

Maine Inside Out was created in 2007, and at first the group did sporadic workshops. Today the group has a contract to work with residents of Long Creek, and about 30 people are currently involved there. A couple of years ago, Maine Inside Out expanded so that meetings and workshops could be held for recently released youths, and about 45 people are currently involved with the program that way, talking to each other and creating original theater pieces. The funding comes mostly from grants and contributions, Seward said.

Maine Inside Out groups for former prisoners meet once a week in three cities: Portland, Biddeford and Lewiston. Each session begins with everyone sitting in a circle, listening to one person at a time talk about whatever is on their mind. Then people warm up with theater games and exercises, followed by storytelling and writing. The sessions usually last 90 minutes to two hours.

Programs in other states also have used art or theater to help incarcerated youth and to try to change the system, said Jill Ward, a juvenile justice consultant in South Portland who works with The Youth First Initiative, which aims to reduce the number of young people jailed nationally and to create a system that relies instead on group homes or other alternative facilities.

Ward says studies show that teens who go to jail are much more likely to be arrested again than a youthful offender who is not locked up. Some recent studies show that, in some states, 70 percent of incarcerated youths are arrested again within two to three years of their release.

In Maine, about 33 percent of released youths were rearrested within a year, according to the 2012 Maine Juvenile Justice Data Book, compiled by the University of Southern Maine’s Muskie School of Public Service.

Maine’s youth arrest rate also has decreased over the years, from 67 arrests per 1,000 youths in 2001 to 50 arrests in 2010.

“I think programs like Maine Inside Out are working in a few places, because they give these kids a voice and educate the public,” said Ward. “It helps in their rehabilitation to know people are listening to what they’re saying.”

STUDENTS REACT TO PERFORMANCE

After the performance at Bonny Eagle, the 200 students in the audience applauded wildly. Several thanked the group members for sharing their stories, and thanked Dumbrocyo for his apology.

One student, junior Bryn Worthington, asked everyone in the audience who forgave the members for their past to stand up and show them. Everyone in the crowd stood.

“His apology, and the performance, were just really amazing and touching,” said Bryn, 16, of Hollis. “It motivated me to want to be a better person, to see what they’re doing.”

During a question and answer session, several students asked the group members about how they first got in trouble, about what being locked up was like, and how they made the decision to change.

“You realize how much you miss things, like feeling the sun, or eating whenever you want,” said Abdulkadhir Ali, 21, who is the group’s artistic director and spent 18 months in Long Creek after an armed robbery arrest.

Gabe Olson, 20, of Biddeford, told the crowd that he too missed little things, like making his own sandwich. Olson grew up in foster care and ran away from a group home when he was 13. That led to more run-ins with police, and he ended up spending about five years locked up.

Now, after being out for two years and with help from Maine Inside Out, he’s a student at USM and hopes to become an art therapist.

“I lost most of my teenage years,” he told the students, “and I just realized I didn’t want to lose any more time.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.