Instead of showing slide after slide of his own work during a talk at the Bates College Museum of Art opening of “Phantom Punch,” the Saudi artist Ahmed Mater spoke at length about how he and his colleagues are working together to build a contemporary art scene in Saudi Arabia. One would imagine that Mater, a doctor, would talk about healing and nurturing the existing system, but he and his colleagues are part of building a new model for contemporary art from scratch.

Mater explained that Saudi Arabia has no history of art infrastructure for the public consumption of contemporary art, such as communities of art galleries or kunsthalles. Moreover, because of social media, this is a time of seismic shift in culture consumption. While Americans generally see the core of the art scene as the object market for works of art – galleries, collectors and the museums they support – Saudi contemporary artists are building a foundation with very different kinds of bricks. And Mater and his colleagues are doing this with the support of the state: “Phantom Punch” is produced and funded by the King Abdulaziz Center for World Culture, a Saudi Armco Initiative.

But where some see a desert, other see a blank canvas. “Phantom Punch” sizzles and sparkles in the academically open-minded and intersectional museum space, but underlying it is an anxiety about how to create a functional contemporary art culture for Saudis.

Under the site, the effervescent color and the unapologetically indulgent aesthetics is a quiet call for help. It is this call that make “Phantom Punch” so engaging and so unusual. It is an exhibition that reaches out to viewers – to us.

Arguably, there is only one object on the first floor that is not obviously connected to images of traditional garb and objects like carpets and prayer rugs: a giant sculptural ball of black microphones. The mic ball is by artist Ahmad Angawi, who hosts open mic nights dedicated to free speech in Jeddah where you people share poetry, opinions and debate.

Angawi’s art, in other words, is community and cultural engagement. This is the underlying critical current of “Phantom Punch,” but it only really comes into focus during significant time spent in the show.

And it is worth spending a great deal of time in “Phantom Punch.” It is also quite easy to do. A particularly engaging and entertaining aspect of the exhibition is a video viewing room replete with couches and carpets from which to view a looped hour or so of short videos. These range from hilarious to just plain weird, but all are highly entertaining. According to Mater, Saudis are the world’s leading consumers of YouTube content. Some of these videos, like Telfaz11’s “No Woman, No Drive” and the media company’s cover of Pharell Williams’ huge hit “Happy,” have been viewed many millions of times. (Telfaz11 references the 2011 Jasmine Revolution, generally known in the United States as the Arab Spring.)

The most hilarious and engaging video for me was “Infidels,” from Mykott studio’s Masameer series of political satire videos. It acts like a rap video with two tie-dye wearing culture-conservative protagonists who take a thug-life approach to upholding traditional values. Parody isn’t obvious when you aren’t familiar with its target, but when one of the protagonists raps and rages about a guy’s “new best friend” – his dog – and then turns around and punts the pooch (or, rather, an obviously stuffed stand-in), the message and the over-the-top humor become clear as day.

“Happy,” on the other hand, is subtle: If you ask yourself why tens of millions of people would watch people in Saudi garb lipsync to a Western hit, the message of engagement and shared experience starts to sink in.

Many of the art objects in this show are clear. Ahmed Mater, a former doctor, spoke brilliantly before the exhibition opening about building a new contemporary art scene in Saudi. Mater’s “Evolution of Man” switches, in five steps, an image of a gas pump to an x-ray man with a gun to his head.

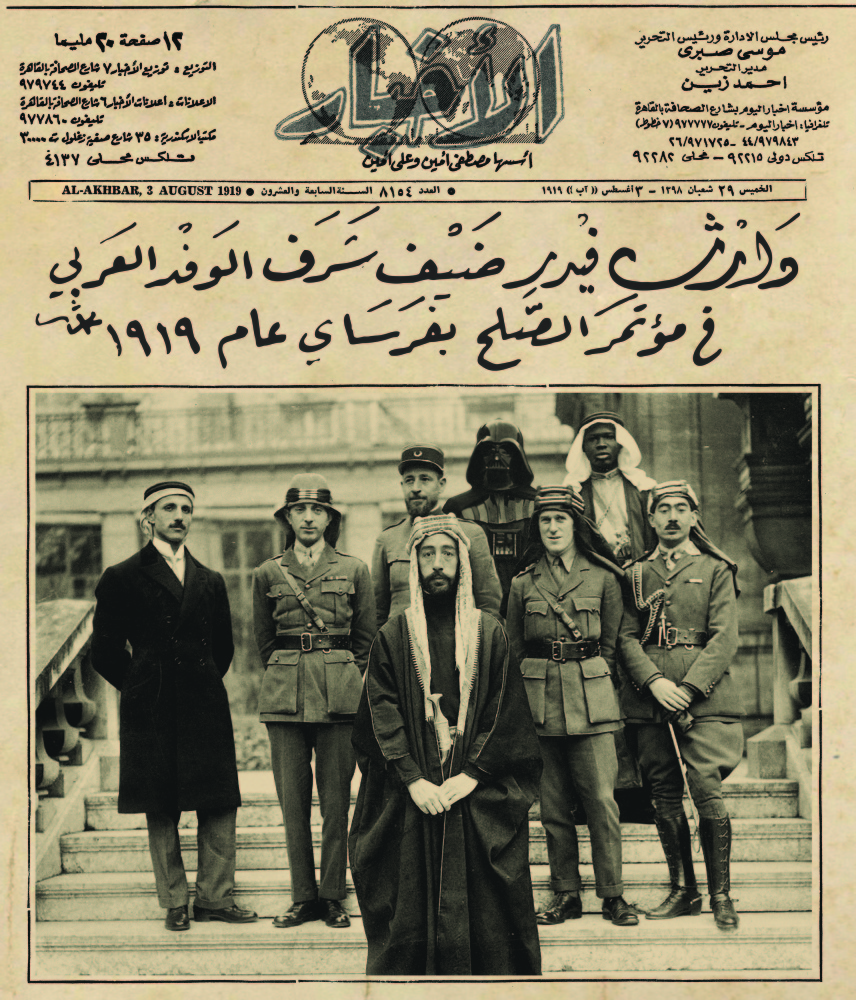

Shaweesh’s dark snicker-worthy poster blowups show old newspaper photos in which we learn the Nazi-helmeted Darth Vader was present in Saudi Arabia in 1919 and Captain America showed up during WWII. Musaed al Hulis’s motorcycle chain prayer rug, “Dynamic,” is beautiful but not practical for human knees.

Abdulnasser Gharem’s works are particularly exciting. His “Ricochet” is a giant image of a fighter jet that morphs upwards into traditional architectural decoration. “Ricochet” and his photograph of artists working from a mannequin are the closest thing to plain-old paintings in the show. The actual mannequin is an unlikely star. Its labeled and reassembled bits reveal how it was cut into chunks to be smuggled into Saudi Arabia, where mannequins are illegal.

Arwa Al Neami’s photos and videos of women in black hijab driving bumper cars set the baseline for “Phantom Punch.” Women can’t drive in Saudi Arabia. Are these scenes good fun or seeds of subversion, something else or both?

Houda Beydoun’s images from the “Documenting the Undocumented” series were picked up by Banksy for “Dismaland.” Bedoun’s images show foreign workers in rather crude documentation-like black and white photos, but the figures are covered in colorful blocks and shapes referencing Mickey Mouse. It’s a nuanced view that reaches from the very bottom up into the synchronized systems of society.

Nouf Alhimiary’s three photographs of a traditionally dressed woman under water somehow find real boundaries and yet manage to reach across them. The pool water and images are clear and bright. But the water distorts the image. Bubbles come from the woman’s mouth. Is she calling out? The response to such an image is physical; we don’t need to learn what drowning is. And we don’t need to speak her language to understand her message. But as a photograph, she will be perpetually held under water. And while the bubbles are unheard words, they are also steps in her process of drowning. Alhimiary is challenging us: Is it enough to be aware? Or is action necessary? (I found it stunningly ironic when Alhimiary told me that, when she was in Lewiston on exhibition business last week with a group of 10 men, she was verbally abused in English by a local Muslim woman for not wearing hijab. None of the men, a mix of Saudis and local Americans, spoke up or defended her.)

Without a robust community of art venues, it makes sense the contemporary Saudi art scene would take form through social media and develop a discourse of memes combined with internal traditional imagery. YouTube, after all, is a battleground for the hearts and minds of young Saudis: ISIS has its own powerful presence. So groups like Telfaz11 are playing a very serious game with folks who showed what they were willing to do in the Paris offices of Charlie Hebdo. And because 60 percent of Saudis are now 30 years or younger, these artists are trying to build a new cultural path forward for an ever younger and more technologically savvy society.

These Saudi artists came to engage and learn what they could from our art culture. But “Phantom Punch” also makes the case that we have much to learn from them.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at dankany@gmail.com.

Correction: This review was updated at 4 p.m. on Nov. 6 to replace several paragraphs that were accidentally left out.

Send questions/comments to the editors.