GEORGETOWN — Charlie Ipcar pulls heavily on the shed door handle, tugging it loose from its own weight and sliding it slowly open. He walks into Maine art history as he steps up into the small building, where the floors are worn and weathered and the wooden walls covered with a patina that only comes with a century of age. Along one wall are several old metal filing cabinets, with yellowed name plates marked “Zorach” and “Ipcar.” There’s a large work table for framing, and off to the side, newly built storage cabinets.

The son of painter Dahlov Ipcar, Charlie Ipcar has spent much of this year bringing order to this place, which was built as an apple shed and has served many purposes in the long life of the farm, most recently to store artwork that spans decades.

Last spring, Ipcar uncovered many long-forgotten pieces – terra cotta animal sculptures that Dahlov Ipcar made when she was a child, large pastel murals of German soldiers from World War I inspired by the novel “All Quiet on the Western Front,” and as many as 100 paintings, many of which were part of her first solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1939.

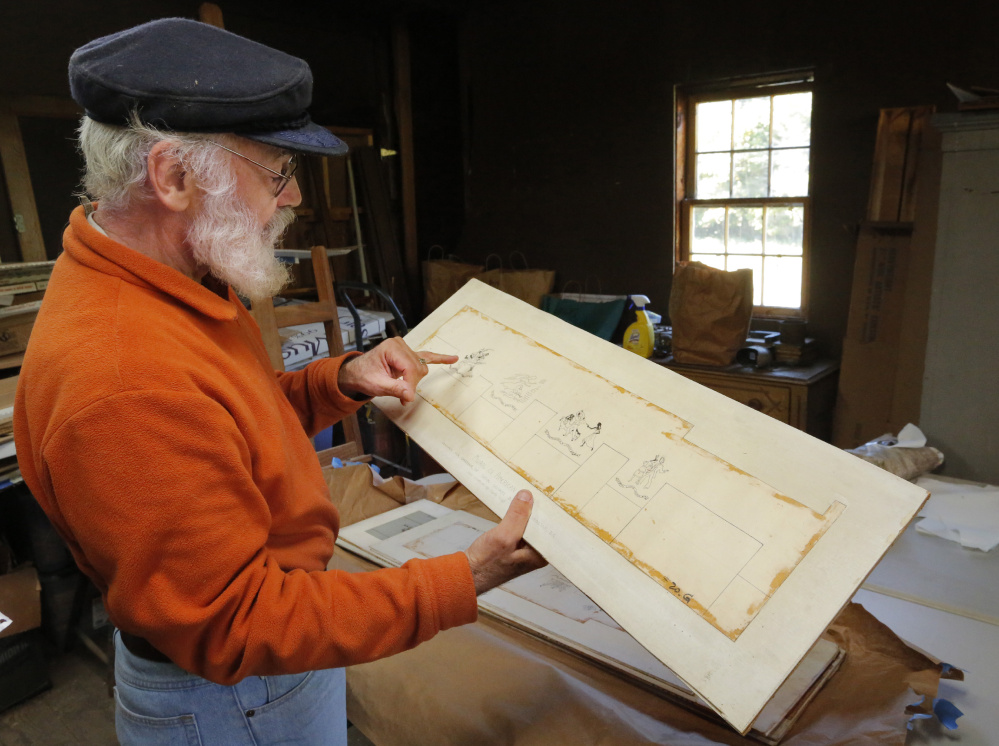

One thing stood out. In a corner, wrapped in paper, a half-dozen particle boards stood on end, hand-painted with lyrics from old American folk songs and illustrated by scenes described in the lyrics of the songs. The largest was about 40 inches long and 10 inches high. Ipcar made the panels for a mural contest at the Social Security Administration cafeteria in Washington, D.C. in 1939.

Inspired by his find, Charlie Ipcar and several musical friends will sing the songs that Ipcar illustrated in her Mural of American Songs at 7:30 p.m. Friday at the Unitarian Universalist Church of Brunswick. They’re calling their concert “An Evening of Dahlov Ipcar’s Favorite Songs.”

Dahlov Ipcar, who turns 99 on Nov. 12, will attend the concert, but won’t sing.

“I never was a singer,” she said. “I was off-key and had no sense of rhythm. But I loved to sing, and I sure loved the songs. Music was a great source of my interest.”

Ipcar clearly remembers making these mock-ups, though she cannot recall if there was a specific inspiration. “I guess I just got the idea. I always liked folk songs, and I guess I thought it would be good for cafeteria walls,” she said.

Murals, she added, also were a great source of income, which is why she entered contests. She earned about $600 for each mural she painted. “That was a big deal in those days. That was enough money to keep me alive for a year,” she said.

Her mural proposal was part of a Works Progress Administration effort, a New Deal-era government program designed to put artists to work and beautify America. Ipcar won other mural commissions, for post offices in Tennessee and Oklahoma, but she didn’t get this one. The Mural of American Songs died with the rejection, her panels lost to 70 years of dust until her son started cleaning.

Charlie Ipcar found six boards, which illustrated a total of 18 songs. Two were in color, painted directly on the boards. Four were black and white sketches on paper taped to the board. They are in good shape overall, and he is working with an art conservator to prepare the color panels for framing. The artwork will be projected on screens during Friday’s concert.

When he looked closely, Charlie Ipcar recognized many of the songs as tunes he heard around the house while he was growing up. He and his older brother, Robert, listened from upstairs while his parents entertained friends around the family piano. “One of their social entertainments was song parties,” Charlie Ipcar said. “Songs were their form of entertainment. There were ballads, drinking songs and folk songs.”

“The Arkansas Traveler,” detail, from the mural studies created by Dahlov Ipcar. Gregory Rec/Staff Photographer

Those early song parties made a lasting impression on Charlie Ipcar, who has spent much of his life making music. He formed his first folk group at Bowdoin College in 1960, and he has been active in Maine folk circles since, specializing in sea shanties.

When he showed the panels to his mother, she remembered all of the songs and began singing some of them, including an alternate verse to the classic song “Frankie and Johnny” that Charlie Ipcar had never heard. Many of the songs are American standards – “The Arkansas Traveler,” “Casey Jones” and Jimmie Rodgers’ “Mule Skinner Blues.”

This project highlights the influence of music in his mother’s life, Charlie Ipcar said. In the months since the discovery, he’s had many conversations with her about these songs, the song parties and how music influenced her view of the world. The other panels that she won commissions for, and that are still on view at post offices in Oklahoma and Tennessee, involve the settling of America and the country’s legacy of hunting and fishing. Those themes, along with folk music motif, demonstrate that his mother was thinking broadly about American culture and the American experience, he said.

Ipcar, who still sings herself to sleep, is thrilled with the attention to her interest in music. “It’s an aspect of my life that people haven’t delved into,” she said. “And it’s an important part of my old life.”

She began listening to music as a little girl in New York City. Her father hired a nanny who had a beautiful singing voice. The nanny, Ella Robinson Madison, sang gospel songs and minstrel songs to Ipcar and her brother, Tessim. In addition to entertaining the kids with “marvelous spirituals,” Ipcar remembers Madison as a loving woman who took the kids to Washington Square Park, where they often sang and performed for strangers. When Ipcar was about 10, her parents arranged an audition for Madison, who was cast in a play called “Porgy” that called for “old Negro folk songs.” A few years later, the play evolved into the opera “Porgy and Bess” by George and Ira Gershwin.

“Mule Skinner’s Blues” detail from mural study created by Dahlov Ipcar in the 1940s. Gregory Rec/Staff Photographer

Ipcar attended a progressive school in Greenwich Village, where music was a daily priority. The students sang songs from the 1916 songbook, “One Hundred English Folksongs.” Ipcar has a copy of the book on her shelves in her Georgetown home.

After she and Adolph moved to Maine in 1937, music became more important because it helped connect the family to the outside world, she said. They listened to Ken MacKenzie’s radio show on WGAN out of Portland, which began in 1939. Later, the Ipcars befriended Maine folklorist Bill Bonyon. Adolph ran into Bonyon at church and asked, “How do you know these songs and where did you learn them?”

Bonyon became a family friend and taught the Ipcars songs and how to play them.

In addition to singing songs with friends around the piano, Ipcar recalls having a xylophone in the house. At some point, Adolph bought her “a set of English folk records because he got tired of hearing me singing to myself.” She taught her boys songs by Woodie Guthrie, Leadbelly and Burl Ives long before the popular folk movement of the 1950s.

In addition to painting song scenes on the mock-up for the mural, Ipcar also illustrated songs on the kitchen wall of the family’s Georgetown home. Those illustrations have long since been painted over, but very likely are preserved under decades of paint. “Someday, they will take the paint off and there they’ll be,” she said.

The paintings themselves might qualify as folk art. These are directly representational paintings of scenes portrayed in the songs. “The Arkansas Traveler” shows country people dancing, and “Don’t Go in the Lion’s Cage Tonight” depicts a lion eagerly awaiting the arrival of an unsuspecting trainer – and the trainer’s daughter pleading with her mother to stay safe.

Charlie Ipcar was impressed that in her illustration for “The Ballad of Casey Jones” about a railroad engineer who dies at the controls, his mother got the initials of the railroad accurate, the CB&Q, for the Chicago and Burlington and Quincy Railroad. “She was paying attention,” he said.

They’re simple, figurative drawings, made with a flair that suggests the style of an evolving modernist. Ipcar was 21 at the time, and accomplished. In 1939, the same year she made these murals, she had her first solo show at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. She received attention for the exhibition, which focused on her early prolific career.

Ipcar’s art would evolve many times in the decades ahead, moving from early social realism through book illustration to mid-century modernism. She remains best known for her wildly imaginative paintings of wild and domestic animals. Though frustrated by declining eyesight, she paints nearly every day.

This past spring and summer, as Charlie Ipcar cleaned the old apple shed, he found all the work from the Museum of Modern Art show boxed up in dusty wooden crates. Ipcar never saw the show, which opened in November 1939. She was home in Maine, on the farm. She had her first child in September and wasn’t interested in leaving the baby at home or traveling to New York with an infant.

She’s glad she waited. In 2017, the year that Ipcar turns 100 and 77 years after the exhibition opened in New York, the Ogunquit Museum of American Art will remount the MoMA show, or much of it. And Dahlov Ipcar will finally get to see it.

First up is Friday night’s concert. She’s looking forward to hearing these songs again. “I’ll be interested to hear what they sound like, and I hope people are dancing in the aisles,” she said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.