As Mainers prepare to help elect a new president, the Maine Sunday Telegram visited voters in Turner and Hallowell, two comparably sized towns just 35 miles apart, each hugging a major river and adjacent to an important city. One is a bastion of anti-government conservatism, the other is home to the most liberal electorate outside of Portland. Residents of the two towns, which lie in separate congressional districts, describe their communities as tolerant, neighborly, caring and civically engaged, but they come to opposing conclusions about how best to sustain a healthy town, state and nation. The differences help shed light on a growing chasm between the state’s rural interior and the often more affluent communities of the coast and former shipping centers on the lower Kennebec and Penobscot rivers.

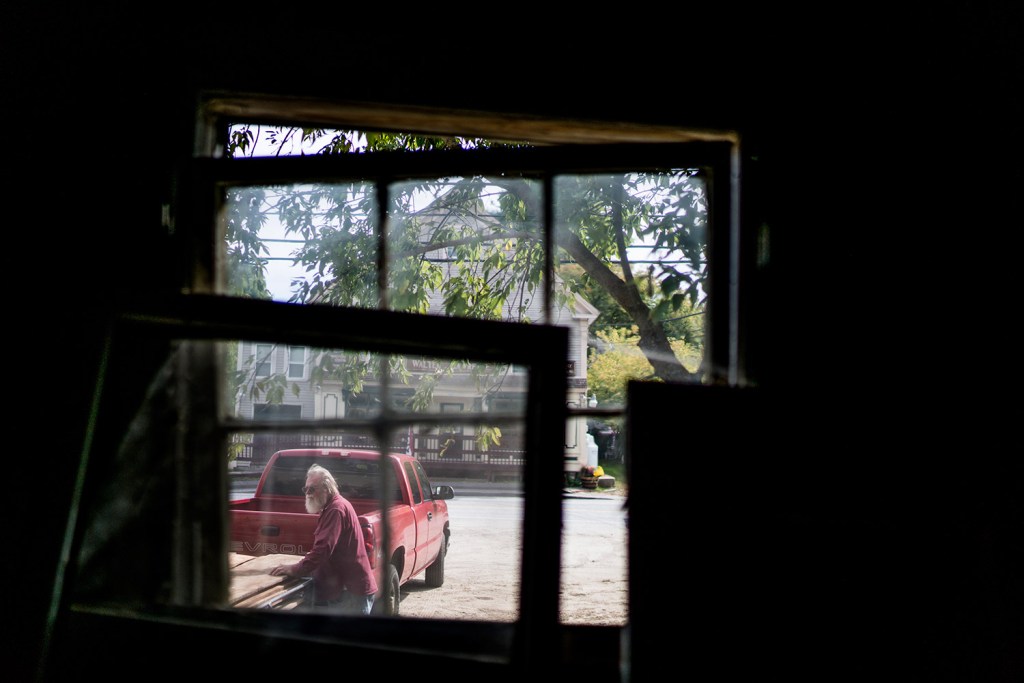

TURNER — Ralph “Rass” Caldwell, patriarch of a beef farm purchased by his father 72 years ago, has a lot of beef with the federal government.

New environmental protection rules forced him to relocate a planned grain silo, to truck water for irrigation and livestock around the 1,000-acre farm and to fence his cattle off from a creek that’s dry most of the year.

“It was salamander habitat, and salamanders return to the brook they were born in, and so you might stop a family of them forever,” Caldwell explains, seated at his home in the midst of the bustling farmstead. “You know what? I don’t give a damn if that salamander dies.” Our food supply, he adds, is more important than protecting amphibians or restoring salmon to the Androscoggin watershed.

“We’ve got some reasonably serious problems because the government is on the wrong side continually and we’ve just gotten awfully sick of it,” he says, which is why he’s voting for Donald Trump for president. “He’s going to shake some trees, there’s no doubt about that, and they damn well need shaking.”

In a state full of conservative rural towns, this farming community of 5,800 just north of Auburn is among the most conservative of all. One of the state’s most important agricultural centers for nearly two centuries, most of Turner’s biggest farming families have managed to hold on to their way of life, innovating, diversifying and – perhaps most important – persuading their neighbors to keep taxes low, services lean and infrastructure projects frugal.

In 2014, voters here reelected Governor Paul LePage by the largest margin of any town casting at least 1500 ballots, save neighboring Greene, a rural hamlet that sends its students to Turner’s Leavitt High School. LePage even chose the town for an hour-long campaign appearance with Trump’s son, Eric, on Thursday.

As Mainers prepare to help elect a new president, the Maine Sunday Telegram visited voters in Turner and Hallowell, two comparably sized towns just 35 miles apart, each hugging a major river and adjacent to an important city, one a bastion of anti-government conservatism, the other home to the most liberal electorate outside of Portland.

Residents of the two towns – which lie in separate congressional districts – each describe their communities as tolerant, neighborly, caring and civic minded, but they come to opposing conclusions about how best to sustain a healthy town, state and nation. The differences help shed light on what polls and recent elections suggest is a growing chasm between the state’s rural interior – much of which lies in the 2nd Congressional District – and the often more affluent communities of the coast and former shipping centers on the lower Kennebec and Penobscot rivers, which dominate the 1st.

“It’s all about the amount you want government involved in your life,” says Jeffrey Timberlake, the eighth generation of his family to grow apples along Martin Creek, who has represented the area in the state legislature since 2010. “We’re not wanting you to take our money to save us. Leave us alone to take care of our community.”

EMBODYING JEFFERSON’S VISION

Turner’s community has been taking care of itself since the first settlers started clearing land in 1772. The soils proved ideal for grazing cows and growing apples, and Turner’s farmers became modestly prosperous, some branching out to build small grain mills around which three small villages formed by the early 19th century: North Turner, Turner Village and Turner Center. Like many rural Maine communities, it embodied Thomas Jefferson’s vision of the ideal republic: an egalitarian society of self-sufficient, independent, civic-minded farmers. Unlike many communities, this ethos and essential social model weathered the challenges of the Industrial Age and survives to the present day, under pressure but intact.

In 1986 Louis Ploch, a rural sociologist at the University of Maine, chose Turner for a detailed study in persistence and change, in part because of what he called the “general reluctance to become involved in the provision of services not traditionally the role of small New England communities.” As a result, Ploch wrote, it was believed to be the only Maine community of its size – over 4,000 at the time – that had no public housing, condominiums or townhouses, bank, supermarket, town manager, local police officer, public water supply or zoning ordinance.

Many of those institutions arrived in the coming years, prompted by state mandates or population growth, as newcomers with jobs in Lewiston-Auburn, Portland or the paper mill towns continued buying and building on house lots, causing the town to nearly double its size between 1970 and 1990. But longtime residents made a concerted and remarkably successful effort to assimilate the flood of would-be suburbanites to their agrarian culture and the advantages of limited government. “Turner,” Ploch would write, “has a way of making Turnerites out of strangers.”

Timberlake describes the outreach effort. “All that time we didn’t stick our noses in the air and snub them – you know, the ‘what are you doing here, we don’t want you in our town’ thing,” he recalls. “Instead, I came around to all of them and said, ‘Welcome. Do you want to join the volunteer fire department or the (all-volunteer) athletic association? We’re looking for some help.'” At town meeting, longtime residents would explain why they didn’t have services like curbside trash pick-up or full-time police and fire departments or rigid site approval rules for farm buildings.

“Farmers are cash poor and land rich,” explains Timberlake, a former selectman. “If you want me to keep this land open and invite you to hunt on it and use it for recreational purposes, you’d better make sure I can afford the taxes on it. If you want all these services, maybe you need to stay in Lewiston-Auburn, because that’s why your mil rates and cost of living are so much higher there.” Today Turner’s property tax rate is a third less than Auburn’s.

Dawn Youland, a lending officer who worked at a Portland bank, moved to town from southern New Jersey in the 1980s. “When I first moved here, if someone outside of town walked into the store, they all stopped and listened to learn about them,” she recalls. “But they are welcoming, and once they get to know you they’ll accept you, so long as they know you’re here for the good of the community.”

“Turner is very liberal in the sense that you don’t have to be a Ricker or a Leavitt – everyone is able to take a seat and we listen to one another’s perspectives,” she says. “There’s a sense of oneness, of protecting and being there and supporting one another.”

People are civic minded, but the emphasis is on volunteerism. People donate their time and services to keep the volunteer fire department going, to build the community center, to maintain athletic programs.

“If somebody comes and wants something from the town and they are doing it for nothing, I’m certainly going to try to help them get what they need to get it done,” says Caldwell, who is a town selectman. “But if there are big salaries involved in the organization then they don’t get any money from the town of Turner.”

‘TRUMP – FOR CHANGE’

Neither presidential candidate is clearly championing Turner’s brand of small government conservatism, but many see Trump as more likely to change a status quo few are happy with.

Youland says she plans to vote for Trump, though he wasn’t her first choice, and she’s got some firsthand experience to draw on: She was one of Trump’s casino floor managers in Atlantic City, met the man many times and was known by name by Ivana Trump, the candidate’s first wife. “He was terrific to work for and he held you accountable, but we got paid well and our benefits were awesome,” she says. “He’s not as polished as a lot of the other candidates, but he’s a strong leader.”

Gregg Varney runs what was the first certified organic dairy farm in Maine with his wife, Gloria, who were named Homesteaders of the Year by Mother Earth News in 2013. He says he’s never been so disappointed in the choice of presidential candidates, but he’s made his pick. “Eight years ago, the world had some promise – Iraq and Afghanistan were winding down, the Arab Spring was happening, we had a decent relationship with Russia,” he says. “It’s all gone away, and the world’s gotten a lot scarier, and we got a lot weaker, and Hillary Clinton played a big part in that. I’m going to vote for Donald Trump – for change.”

Trump says a lot of things he shouldn’t, Varney says, but so has Gov. LePage, and that’s not a deal breaker by itself. “There’s a lot of us who are very disappointed with this political correctness, of having to be perfect all the time, to have what you say come out right the first time,” he says. “We don’t always agree with LePage, but we understand him, we can see the good in him. People that have the tolerance to look beyond the words can see something good in both LePage and Trump.”

Timberlake is campaigning for re-election to the legislature, so he knocks on lots of doors. “I can tell you from talking to people that nobody is really happy with either choice – Donald Trump has his baggage, and Hillary Clinton has her baggage,” he says. “But you’ve got to make a decision when you get into that booth and pull the curtain. The Democrats and the Republicans can’t get along in Washington and I think people think maybe it needs a big shakeup, like what LePage did here.”

Caldwell says one of the reasons he supports Trump is that he agrees that foreign trade agreements have been killing American jobs and that recent imports from Latin America are undermining the prices farmers get for beef and cider-grade apples. He’s hopeful that a Trump administration would roll back heavy-handed environmental regulations like the ones pushing his operations back from a seasonal creek. But most of all he thinks the candidate will turn a shrewd deal maker’s eye on government contracts and spending.

“He’s spending like 10 cents on the dollar compared to what Hillary is, and he’s still getting the (campaign’s) job done,” he explains. “And if he could run the country like that, wouldn’t it be wonderful? He’ll run it like a business.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.