The first tip came on Aug. 23, 2013.

A confidential informant overheard Adnan Fazeli expressing anti-American rhetoric at an Iraqi market in Portland and contacted a local FBI agent. It was around the same time Fazeli left his home in Freeport to go fight – and ultimately die – with Islamic State terrorists in Lebanon.

Over nearly two years, the FBI received other tips and information about Fazeli’s activities and whereabouts from his own family members and other unnamed sources, according to interviews and a court document unsealed Monday that publicly revealed the case for the first time.

Two relatives in the Portland area – Fazeli’s brother and his nephew – said last week they were among the people who cooperated with the FBI.

“I knew that my aunt was going to be investigated. I knew that my dad would probably be investigated,” Ebrahim Fazeli said about the decision to talk to investigators. “I had to do the right thing.”

Members of the local immigrant community, a national terrorism expert and law enforcement officials told the Maine Sunday Telegram they are not surprised Fazeli’s family members and acquaintances reported him to authorities. In fact, the Maine case mirrors other investigations across the country that began with tips about potential terrorism suspects from fellow Muslims, sometimes family members.

In the first 12 years after the Sept. 11 attacks, members of the Muslim-American community directed law enforcement to 54 Muslim-American terrorism suspects and perpetrators, out of 188 cases where the initial tip was made public. That compares to 52 individuals who were identified during U.S. government investigations, according to research from Charles Kurzman, a professor of sociology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and co-director of the Carolina Center for the Study of the Middle East and Muslim Civilizations.

“There’s a clear amount of concern in these instances on the part of the family and community members about the growing extremism on the part of these individuals and their withdrawal from Muslim community institutions,” Kurzman said. “So, far from being an instigator of these plots, mosques and other Muslim community organizations tend to be a moderating role.”

Local Muslims said they would expect extremist threats to be reported to authorities.

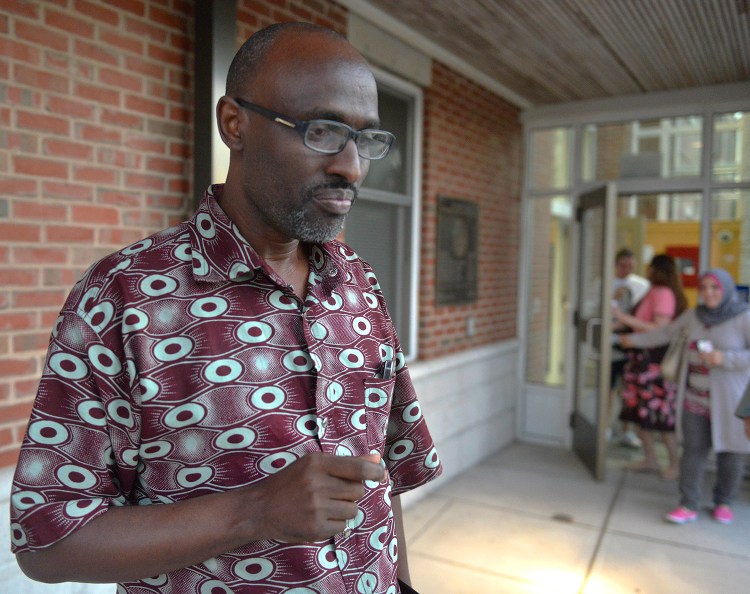

“We do feel responsibility to our community and the community at large,” said Mahmoud Hassan, president of the Somali Community Center of Maine. “When we see a problem, we report it.”

Mahmoud Hassan, who is president of the Somali Community Center of Maine and is shown with his daughters, said, “We do feel responsibility to our community and the community at large. When we see a problem, we report it.” John Ewing/Staff Photographer

PROTECTIVE OF THEIR FAITH

Some seemed incredulous anyone would believe otherwise, saying they do not want their religion to be associated with radicalization.

“This does not represent immigrants, and it does not represent Islam at all,” said Claude Rwaganje, executive director of the Portland nonprofit Community Financial Literacy.

Law enforcement, from local police in Maine to the FBI, said they also have come to expect the Muslim community to share information. They say they rely on it.

“They do not want people committing violence, either in their community or in the name of their faith, and so some of our most productive relationships are with people who see things and tell us things who happen to be Muslim,” FBI Director James Comey said at a news conference after the June shooting at an Orlando nightclub by an American Muslim. “It’s at the heart of the FBI’s effectiveness to have good relationships with these folks.”

A spokeswoman at the FBI’s Boston field office declined to discuss the specifics of Fazeli’s case, although the affidavit unsealed Monday indicates the agency made payments to at least three of the four unnamed informants in exchange for information. Ebrahim Fazeli said he did not receive payments for his help in the case, but he declined to make any additional comments about his role in the investigation.

Other cases of cooperation between family members and the FBI have been documented in other states.

For example, Reuters reported on a 2014 case in which the sister of Abdi Nur contacted Minneapolis police to report her younger brother missing.

He sent the woman messages – saying he had “gone to join his brothers” and promising to see her in the afterlife – that she gave to federal agents. As of June, Nur was still at large but had been charged with conspiracy to provide material support to a foreign terrorist group.

BUILDING TRUST, BOTH WAYS

The Fazeli case and others reflect efforts both by law enforcement and immigrant community leaders to build trust and communication, including in Maine.

For some refugees, those relationships with police agencies are unfamiliar. Refugees often flee countries where violence is prevalent and law enforcement is not trusted.

Rwaganje lived in Westbrook when he first arrived in the United States from the Democratic Republic of Congo 20 years ago. At that time, he said, police officers would pull him over routinely because he was an unfamiliar face in town.

Now, he owns a house in the city, where he attended a meeting Thursday night at the Westbrook police station. Chief Janine Roberts gathered more than 50 members of the refugee community to discuss threats found the day before at the Westbrook Pointe apartment complex – four slips of paper with a typewritten message, “All Muslims are Terrorists should be Killed.”

The meeting was intended to reassure the residents, and to keep communication open.

Rwaganje said afterward he was glad to see the police chief and Mayor Colleen Hilton listening to the community’s fears. Building trust between the local community and law enforcement will help new Mainers feel comfortable alerting police to any kind of crime or threat, he said.

“I don’t want to assume that everything is fine because we talked,” Rwaganje said. “What I heard in the room is, be open-minded to report.”

In a research paper published earlierthis year, Kurzman and his colleagues outlined recommendations for community policing as a strategy to combat violent extremism.

“One of the problems that we identified in communities around the United States, law enforcement agencies took an interest only around issues of violent extremism, which left some communities feeling that their other interests were being disregarded,” Kurzman said. “And that they were being seen merely through the prism of a handful of community members who might be involved in those kinds of acts of violence.”

In addition to the emergency gathering called Thursday night, Roberts’ department has hosted quarterly meetings and a citizens’ police academy with members of the large Iraqi community in the city. Officers meet with individuals or small groups to discuss more personal cases.

In Portland, Police Chief Michael Sauschuck said spending time with the elders and community leaders is important. At times, the elders assist the police and act as mediators in certain situations, he said.

“You want to show respect for people’s culture, to get to know them and understand their religion,” he said. For example, at gatherings in Portland for Eid al-Fitr, the holiday marking the end of Ramadan, he said he likes to “go down and see people and thank them for what they do for the community.”

That trust leads people to feel comfortable calling on the police for help — or to let them know about a problem, he said.

Local residents and experts alike worried, however, about the effect of comments from politicians like Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump and Maine Gov. Paul LePage, who have said the United States should tighten its screening process for Muslims and other immigrants hoping to live in America.

“The community is sometimes treated as sharing in the guilt of an individual who committed violence, when in fact, they were actively trying to prevent the radicalization that ruined that individual’s life,” Kurzman said.

THE BATTLE AGAINST ISOLATION

Muslim institutions and individuals said they are responding to that rhetoric by actively working to integrate new immigrants into American society, including building relationships with local law enforcement and educating newcomers about Maine. Their mission is not only to report threats, but also to prevent them.

Aqeel Mohialdeen publishes the Iraqi language newspaper The Hanging Gardens of Babylon in order to provide a vehicle for people who are learning American culture. John Ewing/Staff Photographer

Standing outside the Westbrook police station Thursday night, Aqeel Mohialdeen held a copy of The Hanging Gardens of Babylon, Maine’s first Arabic-language newspaper. He published the first issue in May. While mentors – people who are “more extroverted and more integrated,” he said – exist in the refugee community, he wanted to create a resource for those who are learning a new culture.

He flipped through the 16 pages – a quote from Abraham Lincoln on the front page, the Bill of Rights on page 3, instructions on how to become a truck driver on page 4, a profile of a local Muslim business owner on page 12.

“Many people, they don’t speak English,” Mohialdeen, 45, said. “They can’t drive. We are trying our best to collect all the information.”

In Scarborough, Latifa Sweri-Fakhouri, 43, is working toward the same goal. With the help of consultant group Trident Star Global, she is trying to start a website to counter the Islamic State’s online presence. The page would include videos and commentary from athletes and celebrities, religious leaders of different faiths, therapists and others, targeted specifically at teenagers.

“It would be a place for Muslims to come to when they feel isolated or not welcome in their society, those who are born here as well as newcomers,” she said.

Ali Farid, a third-year student at the University of Maine School of Law, said he hopes to write a legal column in Mohialdeen’s newspaper after he passes the bar exam.

“When people are left in the dark, they are vulnerable,” said Farid, 26. “We need to take that out of the equation.”

Mohialdeen distributed the first issue of The Hanging Gardens of Babylon for free to markets and businesses run by other Iraqi immigrants. The majority of the first issue is in Arabic, but a full-page ad on the back includes some English. Under a picture of the American flag, the message is printed in capital letters.

“TOGETHER WE STAND TO PROTECT OUR HOME AMERICA.”

Staff Writer Noel Gallagher contributed to this report.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Comments have been disabled on this story because of personal attacks.

Send questions/comments to the editors.