When I first came to Portland, I was invited to join the Committee on Foreign Relations, which used to meet at the Cumberland Club. One of the regulars, not to say stalwarts, was John Lloyd Hadden, a Brunswick resident. It was an accepted fact that John, like a number of retired people living on the midcoast, had worked for the CIA. After spending some enjoyable dinners together, we became good friends.

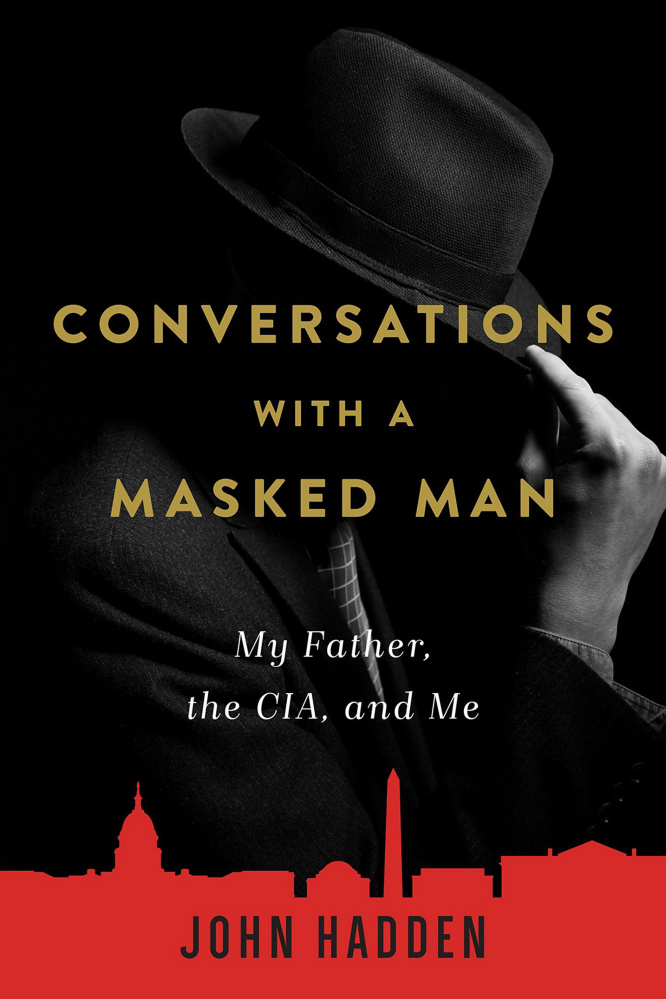

John died in 2013, but his son had the enormous good sense – and fortune – to tape a series of interviews with him some 10 years before. An actor, John Hadden Jr. first turned them into a one-man show. Now he has published the interviews as a book, “Conversations with a Masked Man.” They are riveting from every angle. The book is a marvelous, if a bit idiosyncratic, commentary on American foreign relations and the CIA more or less since the end of the Second World War. Powerful names like James Jesus Angleton and Richard Helms “orbit … [Hadden’s] career like large planets.”

The Agency’s new recruit arrived at his first posting, Berlin, in the middle of the Air Lift. The author was born there. The new father was supposed to pick up wife and son from the hospital, but as luck would have it, East German workers rebelled against the government that day, and he was “running around East Berlin watching the riots. Playing the game!”

For much of the ’60s, Hadden was in Israel. On one occasion, a family picnic was organized near the Israeli nuclear facility, cover for collecting samples from shrubbery growing there. On the basis of the radioactive traces in the cuttings, Hadden proved the original uranium was spirited out of an American plant. When, during the Six Day War, he received an irresponsible order to OK the Israeli bombing of Cairo, he ignored it, he tells his son.

Another facet of this compelling book is the study of a man for whom wearing a mask was innate. Without recourse to any bogus psychologizing, the son tries to draw a picture of his father’s inner life. He gets little help. Life is “just a matter of luck,” his father says. “We come out of nowhere, we rent a room for a night, and then we’re gone.” One thinks of the troubled characters of John LeCarre. Or, as the author does, of Lewis Carroll’s Father William.

Unsurprisingly, the relationship between the two men was anguished. They were frequently at loggerheads, “mostly about politics” starting when the son was 12. “I loved hearing him tell the story,” he writes at one point, “and I felt proud of him, but I didn’t want to feed his ego. It’s a little mean – but he never wanted to feed mine.” Doubtless these recordings were a way to work through a lot of personal conflict.

The younger Hadden was at boarding school when he realized his father was a spy. Suddenly oddities like the Dimona picnic, or finding a drawer full of handguns, came into focus. “Bits of memory were knocking loose like old plaster, revealing the bricks underneath,” he writes in his typically graceful style. Upon construction of the Berlin Wall in 1961, when the author was only 8, “a cold, gray vein of reality took hold of Pop’s life.”

Hadden Sr. was famous for his ability to create a “labyrinth of clues and deceptions,” and interviewing him gave firsthand evidence of this skill. “To let the reader be lulled and misled, as I was,” the author decided to maintain the interview format in the book. It was a daring choice. Linked by his observations, either for context or opinion, it works well most of the time. As with any conversation verbatim, the thread is sometimes a little hard to follow. Just occasionally, he sounds forced as he eggs or goads his father on.

More often, the results are just what he wanted. For anyone who knew John Hadden, reading “Conversations” will bring back a character who was larger than life. For those who didn’t, it is a fascinating, if bleak, glimpse into the mind of a spy.

Thomas Urquhart is a former director of Maine Audubon.

Send questions/comments to the editors.