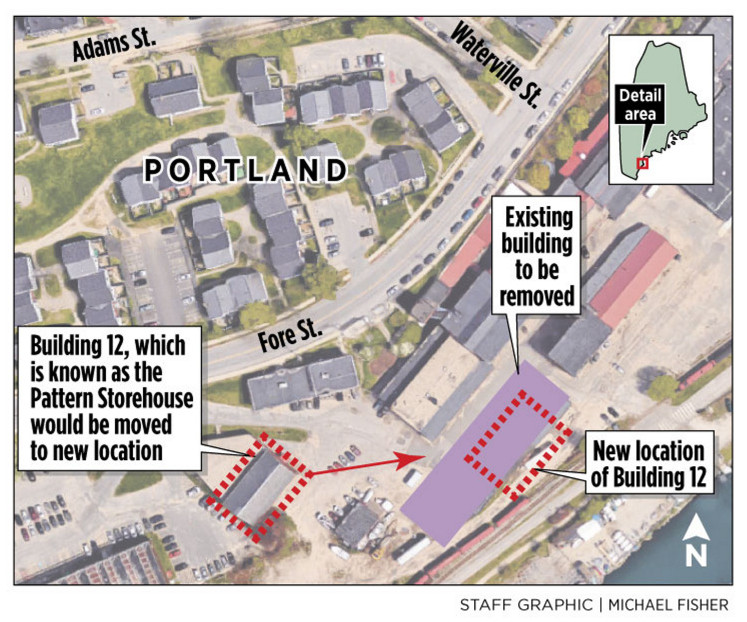

A team of developers wants to relocate a 120-year-old brick building as part of the redevelopment of a 10-acre parcel on Portland’s eastern waterfront.

CPB2 is asking the city’s Historic Preservation Board for permission to move the former Portland Co. Pattern Storehouse so it can add a public road and build a parking garage and mixed-use buildings on the westernmost portion of 58 Fore St. That building is one of seven structures at the former railroad foundry that needs to be preserved during redevelopment because they are part of a historic district created earlier this year.

“The layout and efficiency of these buildings is important to the success of the development,” CPB2 principal James Brady said in a letter to the preservation board.

Founded in 1846, the Portland Co. complex was built to connect Portland to Montreal by rail and was the first locomotive factory in the United States that brought all of the necessary shops and foundry together on one site. It remained in operation for 137 years and was deemed eligible for the National Register of Historic Places in 1976.

The Pattern Storehouse is a 3½-story brick building with a gabled roof and the words “Portland Co.” scrawled across the top.

Built in 1895, it was located away from the core of foundry buildings because of the flammable materials being stored there. The interior is divided into three main floors with wood-planked flooring and exposed brick walls and wood framing, according to an engineering analysis conducted by Sutherland Conservation & Consulting. It is connected to an additional storehouse that was deemed to be a noncontributing structure in the historic district and will be demolished.

MOVING BUILDING 230 FEET TO EAST

CPB2 said in its letter to the preservation board that plans to extend Thames Street would essentially bury the first floor of the building, also known as Building 12, since the new road would have to slope upward to connect to Fore Street.

New public roads are part of the city’s Eastern Waterfront Master Plan, which is guiding the redevelopment.

On the rest of the lot, the developer plans to build a four-story building with parking on the first floor and a mixture of commercial and residential space on three floors above it, further isolating the historic building.

“These proposed developments will enclose Building 12, removing it visually from the context of the Historic Core buildings to the east,” Brady wrote.

He is proposing to relocate the building about 230 feet east and closer to the waterfront. Its final location would be just west of a 50-foot-wide swath of land that is intended to remain public open space. To the east of the open space would be the other six buildings used in the foundry operations that will be preserved and restored.

The Historic Preservation Board first learned about the proposal to move the building after a June 1 site walk. At that time, Brady proposed keeping the building on the western property line, but later proposed moving it closer to the middle of the site, based on board member feedback.

In all, Brady is proposing six new development blocks within the 10-acre parcel, which he said will include a new “world class” marina that is twice the size of the existing one, as well as owner-occupied and rental housing, retail space, offices, restaurants and markets. He has yet to file an application with the city for a Master Development Plan, which would allow his team to build out the project in phases over the next decade or so. That master plan is expected to be filed in the fall.

BRICK BUILDINGS CAN SURVIVE MOVE

Moving buildings was common in the 19th century, but has become increasingly rare as the city has become more developed, said Hilary Bassett, executive director of Greater Portland Landmarks, a local historic preservation advocacy group.

“Moving a building is not an unusual or unprecedented thing,” she said. “A brick structure may be a little different, but it is extraordinary what can be done.”

Bassett said she had not reviewed CPB2’s plans, so should could not comment specifically about the proposal.

Most recently, such a feat occurred in 2009, when the South Portland Historical Society moved a century-old Cushing’s Point house from Madison Street to the city-owned Bug Light Park, where it currently houses the Cushing’s Point Museum. It took an entire day in February for Scarborough-based James G. Merry and Sons to move the two-story brick building with a cupola some 500 feet using a World War II tank retriever, a truck that transported tanks.

“To move a 100-ton building, I was awed and scared a little bit,” said Kathy DiPhilippo, executive director of the South Portland Historical Society.

DiPhilippo said some people doubted that a brick structure dating to the 1900s could arrive at its destination in one piece.

“Lo and behold it was a tremendous success,” she said. “Our building made the trip wonderfully. Once it got onto its foundation it was in really great shape. There were some cracks in the mortar, but that was pretty easy to fix.”

BAYSIDE HOUSE CUT IN HALF, MOVED

Two other historic buildings have been moved in Portland, both of which were wood.

In the 1970s, Bassett said Greater Portland Landmarks moved the so-called Gothic House to make way for the Holiday Inn by the Bay. The home, built in 1845, was moved into the West End neighborhood, where it is a well-maintained single-family home at 387 Spring St., she said.

“Back in the 1970s, there were no protections for historic buildings,” she said. “It was an important example of Gothic architecture in Portland.”

Decades later, the Bayside Neighborhood Association moved a single-family home from Mechanic Street to the corner of Myrtle and Oxford streets. The house was scheduled for demolition in the early 2000s to make way for the Waterview condominium project, which never went forward. Crews cut the house in half and moved it using a flatbed truck, said Steve Hirshon, president of the neighborhood association.

“Rather than tear down a house, we were able to preserve a house and put it on an infill lot,” Hirshon said. “We managed to accomplish two things and that was the only thing that came out of that project.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.