CLEVELAND — Thanks to Donald Trump, the Republican National Convention that opens here Monday will be like none other in the modern era – a gathering of a divided and nervous political party preparing to nominate a candidate who stormed through the nominating process after turning his back on a generation or more of conservative orthodoxy.

In many ways, what transpires in Cleveland will seem familiar. There will be the customary symbols of political conventions – a series of speeches, goofy hats and pins, balloon drops and relentless attacks on the opposition party and its nominee. Party leaders will attempt to project at least a patina of unity to the worldwide audience that will be tuning in.

Yet there will be no hiding the obvious – that an alternate reality forms the true backdrop for this convention, with many Republican leaders worried about what Trump’s candidacy has done to break apart its coalition and what he might do to their overall fortunes in November.

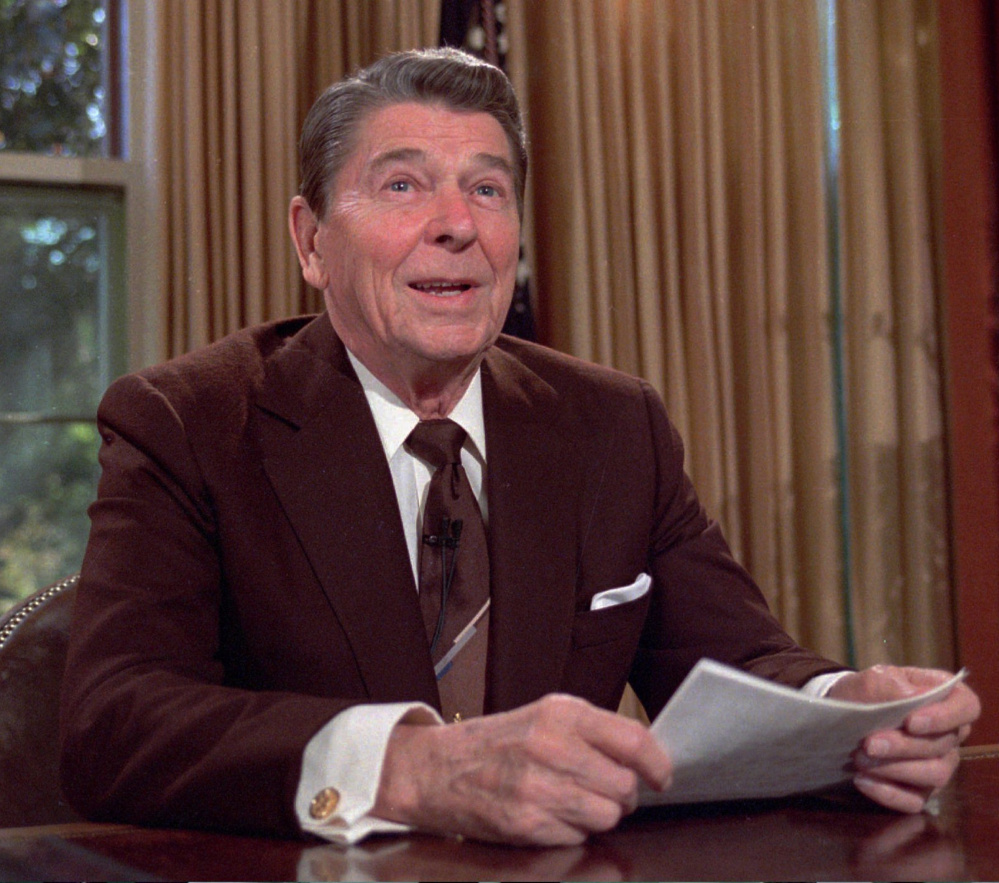

The modern Republican Party has been shaped by many forces, the most important being the presidency and conservative philosophy of Ronald Reagan. It was Reagan who cast modern conservatism in a positive and optimistic light and who moved the party sharply to the right after the debacle of Barry Goldwater’s defeat and the presidencies of two later Republicans, Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford.

REAGAN IN THE REAR-VIEW

Other politicians, movements and events have shaped it since, to the point that Reagan might not recognize – or be welcome in – the party of today. After Reagan came the presidency of George H.W. Bush, which saw an end to the Cold War but foundered domestically. A backbench rebellion in the House, led by Newt Gingrich, helped shorten that Bush presidency but brought the GOP to power in Congress. After Gingrich came a second Bush presidency, that of George W. Bush, who after the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, launched a disastrous war in Iraq that divided the country.

During President Obama’s tenure, Republicans have experienced a grassroots tea party revolt, grand successes in midterm elections that brought the party to a high point of power in the states and consecutive failures in the past two presidential elections that underscored long-term vulnerabilities of a predominantly white party in an increasingly diverse country.

Throughout this period of change, through victories and defeats, the Republican Party and its followers adhered to a set of small-government, pro-defense, socially conservative principles that were consistent and as coherent as any political coalition can muster. Now, in the course of one tumultuous year, Trump has shattered that consensus, exposing divisions that were either overlooked or ignored by the party establishment. As Ohio Gov. John Kasich put it in a recent interview, “I think the party right now is trying to figure out what it is for.”

Trump has changed, at least for now, much of what everyone believed it meant to be a leader of the Republican Party. He is anti-trade in a party of free traders. He wants to keep Social Security and Medicare mostly as they are while others in the party are committed to entitlement reform. He has questioned America’s role in the world in a party long dominated by internationalists and, more recently, interventionists. He has spoken about the LGBT community in ways many Republicans do not. He has put the establishment on notice and ignored their advice when it suits him – which is most of the time.

PARTY’S OVER FOR OLD GUARD

The very fact Trump holds those views rankles many in the party. What adds to their discomfort is that – while espousing those views – he managed to win more states, more votes and more delegates than any of the other 16 Republicans running for president.

The ruptures caused by Trump’s candidacy will be felt in Cleveland, if not always seen. What is left to be answered is whether Trump’s impact is lasting, or that his candidacy proves to be a brief, if unnerving, episode that fades quickly if he loses in November, allowing the party to return to some semblance of normalcy.

Those alarmed at the prospect of Trump at the top of the ticket despair at the state of the party. “I think it’s incredibly divided,” said Katie Packer, a GOP strategist who led a super PAC that tried to deny Trump the nomination. “You have Republican-on-Republican aggression because people are arguing over politics versus principle. Do we stand by the party that we’ve all been loyal to no matter what, or do we stand up and say no, this behavior is unacceptable and I want no part of it under any banner. It’s put people that they’re used to being in the bunker with against one another.”

But defenders of the presumptive nominee have another view of his impact on the party. Pollster Kellyanne Conway, who is now part of the Trump campaign, said the primaries highlighted the fissures within the Republican coalition between what she called the political and voting classes and changed the balance of power between them. “This is the year the voters took the party back,” she said.

Conway, who worked during the primaries for a super PAC supporting Sen. Ted Cruz of Texas, said it was telling that Trump and Cruz finished as the top two candidates in a large field of experienced insiders.

“The Republican Party was veering dangerously close to cementing itself as the party of elites,” she said. “I would look at it as the haughty versus the rowdy in our party. . . . I’m not assigning any negative attributes to that. They’re (the Trump supporters) frustrated. They’re fed up and they feel betrayed.”

THE REPUBLICAN ROAD FROM HERE

No matter November’s outcome, however, Trump’s candidacy has highlighted a party now debating what it actually believes. Vin Weber, a former House member from Minnesota and veteran strategist, said his concerns about the party go far beyond some of the offensive statements Trump has made.

“I’m as offended by that as anybody,” he said. “But … he is rejecting major, major policies that the Republican Party has stood for. … You have to ask that question, what is it that we’ve misjudged about what the Republican Party actually believes?”

Weber’s answer is that Republicans have let their hostility toward Obama, rather than the principles of conservatism, shape what they think about issues. He worries that the anti-Obama sentiment that has bound the coalition together is morphing into anti-Clinton anger, and that begs the question of where the party actually stands on key issues.

Weber said a Trump victory in November could shatter the party.

“I think it will cause a fracturing of the party more serious that we’ve seen up to now,” he said. “I can’t believe that the institutionalization of this phenomenon goes without severe consequences for the Republican Party.”

Conway said the success of the New York billionaire presents Republicans with a choice of what it will be in the future: “Cementing your status as a party of elites or following Donald Trump’s lead and become the party of the workers.”

Kasich doubts the party will break apart but nonetheless sees Trump as emblematic of a broader – and to him worrisome – shift in attitudes here and elsewhere.

“I am increasingly concerned about worldwide – not just in America but worldwide – growing nationalism, a movement towards anti-immigration, a movement toward anti-trade, a movement toward isolation. None of these things am I comfortable with for our country, not just my party, but my country.”

The Republican convention will hardly resolve the differences that Trump’s candidacy has revealed. They will continue to roil the party all the way through to Election Day – and probably beyond.

Send questions/comments to the editors.