LEWISTON — The likeness is striking, uncanny even. It’s Robert Indiana as a young man, with a black cap pulled down over his brow, his eyes conveying a youthful hope. He’s about 30 years old in this photo, taken in 1959.

The image, cropped from a larger black-and-white photo of Indiana with his friend Ellsworth Kelly, is part of the wall-size welcome panel that visitors see as they walk into the Bates College Museum of Art for the newly opened exhibition, “Robert Indiana: Now and Then.”

If you didn’t know better, you’d swear the picture is a young Bob Dylan, whose lyrics Indiana incorporated into works for this show.

Dylan who arrived in New York as a teenager not long after the photo of Indiana was taken. When Columbia Records released Dylan’s first record in 1962, the record label chose a photo of Dylan staring out from underneath a black cap, his collar pulled tight and his youthful eyes capturing an innocence that soon was lost forever. He looks scared.

Two young poets in New York, finding their way.

The artists – Indiana turns 88 in September; and Dylan turned 75 in May – are linked beyond the coincidence of their shared time and place, or their Bohemian sense of fashion. Both are Midwesterners who left home for New York, to chase a dream, to see what the world looked like beyond their familiar farmlands and iron ranges. Both changed their names, not to escape their heritage but to explore the freedom of a new identity that was part of the contract of the American dream.

Both made art, and continue to make art, that is rooted in personal experience and universal in its aesthetic embrace of the promise of a roadside diner, the thrill of a pinball machine and the idea that a railroad line can take you someplace far away. Their worlds, expressed in complex songs and in simple graphic images, were centered on a restlessness that had less to do with youth and more to do with a knowing that there was something more, something better, something different.

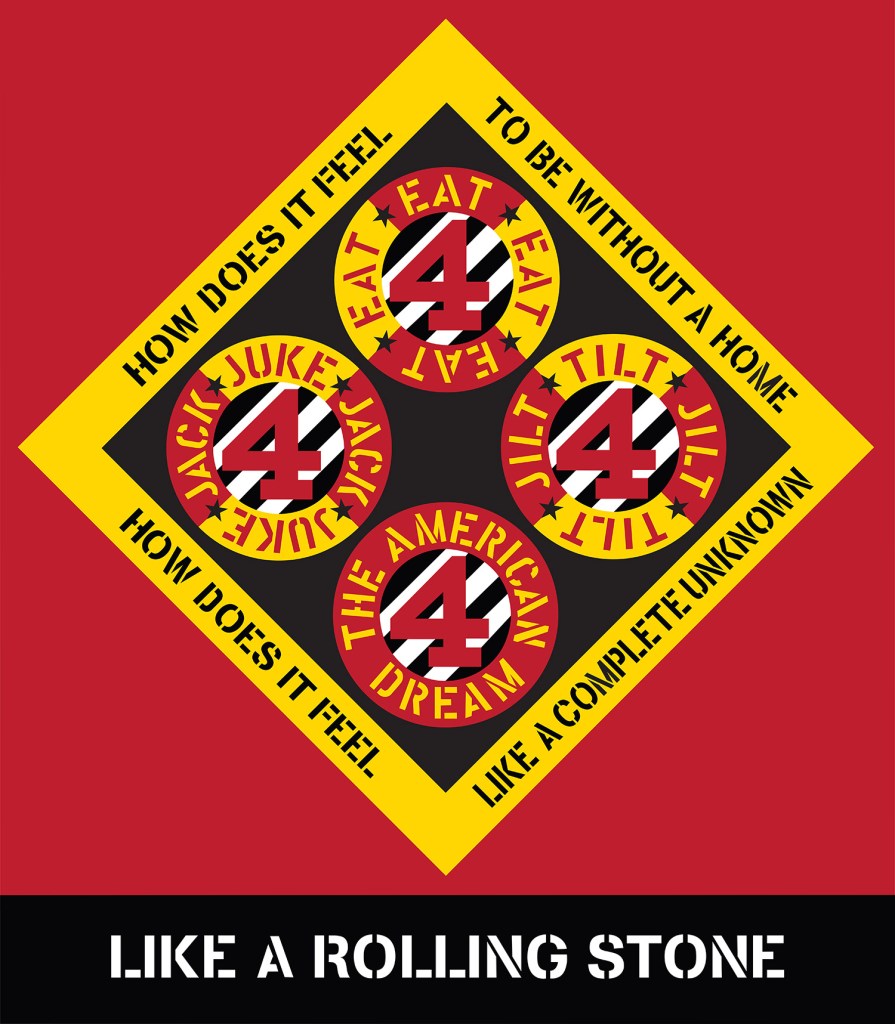

Robert Indiana’s “LOVE,” created in 1966, is one of the most recognized images in American art, expressing the hope and desire – the plea – of a generation to choose peace over war. Dylan’s song, “Like a Rolling Stone,” released in 1965 as the lead track of his “Highway 61 Revisited” album, remade Dylan from charming folk singer into cynical rock star with edge and attitude and snarl.

“How does it feel?” Dylan demanded, pulling back the cloak of innocence. It’s one of the great rock songs, and remains the keynote in a turbulent time in the life of America’s greatest rock star.

Fittingly perhaps, after all these years of walking in the same circles and working from the same vernacular, Robert Indiana and Bob Dylan – born Robert Clark in Newcastle, Indiana, and Robert Zimmerman in Duluth, Minnesota – share the same song and canvas.

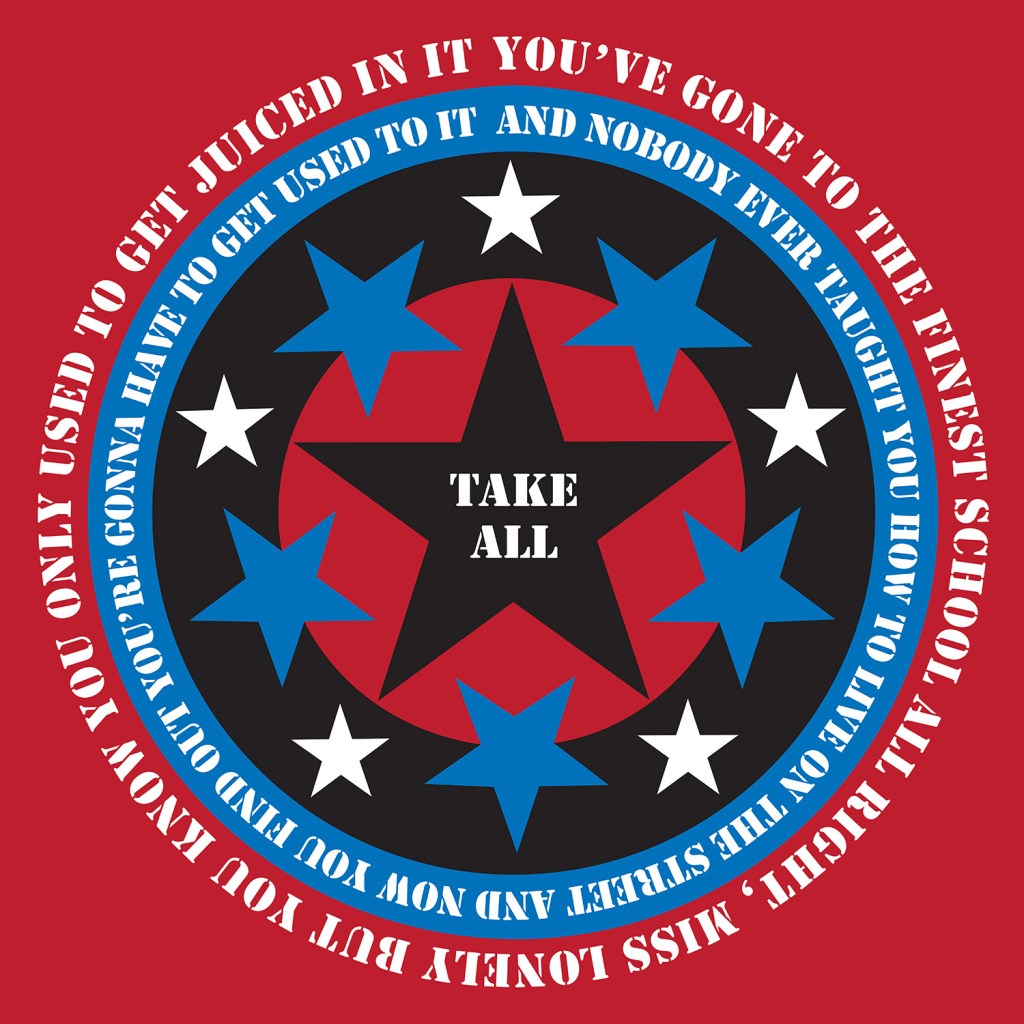

Indiana incorporated Dylan’s words from “Like a Rolling Stone” into a series of 12 new paintings that are mostly based on Indiana’s “The American Dream” series from the early 1960s.

The Dylan-themed work is part of the larger Bates exhibition, on view through Oct. 8. Indiana finished the last piece of the Dylan series six weeks before the exhibition opened in June. This is the first time they’ve been shown publicly.

In what can only be attributed to coincidence, Dylan will be in Portland for a concert on Saturday. Bates Museum director Dan Mills has had no contact with Dylan or his representatives, but said he would happily accommodate the singer if he wants a private tour.

The Dylan series, titled “Like a Rolling Stone,” combines the saturated flat colors that Indiana is known for with text directly from Dylan’s song, presented in billboard-like diamonds, circles, squares and rectangles. Each painting, with a few lines of lyrics arranged around a shape, references one or more early works from Indiana’s own career.

Indiana is best known as a sculptor and printmaker. These are paintings that incorporate print processes, combining acrylic and screenprint on stretched canvas.

DYLAN’S WORDS SPOKE TO HIM

Indiana, who lives on Vinalhaven island and declined an interview for this story, began thinking about Dylan again a few years ago, when Michael McKenzie, a friend and the curator for this show, asked him about influential writers. Indiana has always used words, numbers and phrases in his work, and McKenzie wanted to know who influenced him. If he could collaborate with any writer, living or dead, who would it be?

Indiana named a few obscure writers, then settled on Dylan.

McKenzie said Indiana told his early works were made while listening to Dylan. “He was who I had on in the studio, on the radio, on the stereo. His songs spoke to me. His words spoke to me,” McKenzie recalled him saying.

On a subsequent trip to Vinalhaven, McKenzie brought Indiana a book of Dylan lyrics and asked him to pick out a few songs that were meaningful. Nearly right away, Indiana chose “Like a Rolling Stone.”

Indiana knows how it feels to be without a home, like a rolling stone. He was adopted as an infant, and spent the first 17 years of his life in a dozen homes. It was as if Dylan was singing to him, he told McKenzie.

With Indiana’s blessing, McKenzie went through all of Indiana’s work from the early- to mid-’60s to see if he could identify anything that suggested Dylan’s influence. The original idea was to set Dylan’s lyrics to existing work from throughout Indiana’s career and perhaps to tell a narrative using words and images from both artists.

Instead, Indiana appropriated Dylan’s song lyrics and set them around themes and motifs that first surfaced in Indiana’s “The American Dream” series from the early 1960s. The series riffed on Route 66 and America’s jukebox culture. It was colorful and graphic, and designed around bold letters, slogans and imagery.

Indiana always considered himself an “American painter of signs,” and “The American Dream” series embodied that ideal, and was a precursor for his illuminated “EAT” sculpture at the World’s Fair in Queens, New York, in 1964 – now on view on the roof of the Farnsworth in Rockland – and “LOVE” in 1966. “LOVE” become universally accepted as the image of a generation, and was made into a U.S. postage stamp.

On the strength of “LOVE,” Indiana survives as what McKenzie calls “the crown prince of pop in the living genre.”

“LOVE,” he says, transcends pop.

“You could argue that ‘LOVE’ was the most important art icon of the 20th century,” he said, “and you’d have a really good argument.”

NEW YORK ART WORLD INFLUENCE

Just as Indiana was ascending to taste-maker status, Dylan was reinventing rock ‘n’ roll. From March 1965 to May 1966 – 14 months – he released three records that hinted at the possibility of rock ‘n’ roll and pop music as a literary device, capable of communicating big and important ideas within the context of song and dance, rhythm and blues.

“Like a Rolling Stone” was at the middle of it all, more short story than rock song, and at the time the longest single to hit American airwaves, at more than 6 minutes. In the dash of Al Kooper’s sweeping organ and Dylan’s tempestuous vocal fury, Dylan changed pop culture by blowing it up.

“It’s the definitive Bob Dylan song that we all have in our head, right?” McKenzie said. “Best choice ever? It’s hard to argue. ‘Like a Rolling Stone’ is a pretty important work.”

However briefly, Dylan and Indiana shared a zenith. Their worlds didn’t directly intersect, but both made furious work on the streets of New York that has lasted a half-century.

We know Indiana listened to Dylan. We can assume Dylan saw Indiana’s art – Dylan bought stamps, read the newspapers and magazines. Indiana was showing in the galleries, and in 1961 the Museum of Modern Art acquired a piece from “The American Dream” series.

Dylan’s appetite for the visual arts was fueled by his early years in New York, and his trips to museums gave him ideas about time and space, the destructive nature of man and, above all, the ideal of love.

He surely must have known who Indiana was and, if so, appreciated their parallel lives and common past. Certainly, he appreciated Indiana’s voice, his style and his message.

Their shared moment ended in 1966. Amid the sound and fury of a self-destructive life, Dylan crashed his motorcycle and withdrew to upstate New York with his young family to recuperate, regroup and disconnect.

Indiana’s withdrawal came a decade later. As the biography on his website says, “In 1978, Indiana chose to remove himself from the New York art world. He settled on the remote island of Vinalhaven in Maine, moving into the Star of Hope, a Victorian building that had previously served as an Odd Fellows Lodge.”

He’s been there since.

Both artists remain active, though Dylan’s career has been more prolific.

In recent years, Dylan has found more time for his own art beyond his music. He’s always painted and sketched and dabbled in filmmaking and long-form writing. But the visual arts have stayed with him more soulfully, alongside his music. He has exhibited his oil paintings to modest critical acclaim, and in 2013 he exhibited a collection of welded gates in a London gallery. He called the exhibition “Mood Swings.”

“Gates appeal to me because of the negative space they allow,” Dylan wrote in the gallery brochure. “They can shut you out or shut you in. And in some ways there is no difference.”

Dylan and Indiana have never met. McKenzie tried to arrange a meeting once, backstage at a Dylan show. But Indiana wanted McKenzie to bring Dylan to Vinalhaven, which is something, McKenzie said, “I don’t have the ability to do.”

Fittingly, somehow, Dylan is touring these days on the strength of two recent records of American standards made famous by Frank Sinatra, songs like “Stay With Me” and “All the Way.”

Love songs – beautiful, aching, ever-lasting songs about love.

Send questions/comments to the editors.