BATH — Elizabeth Knowlton waited at the stove for the chopped bacon to start sizzling. It would add flavor to and also be the finishing touch for her grandmother’s fish chowder.

The chowder is a thin broth of fish stock and whole milk filled with chunks of haddock, carrots, celery, leeks, onions and potatoes.

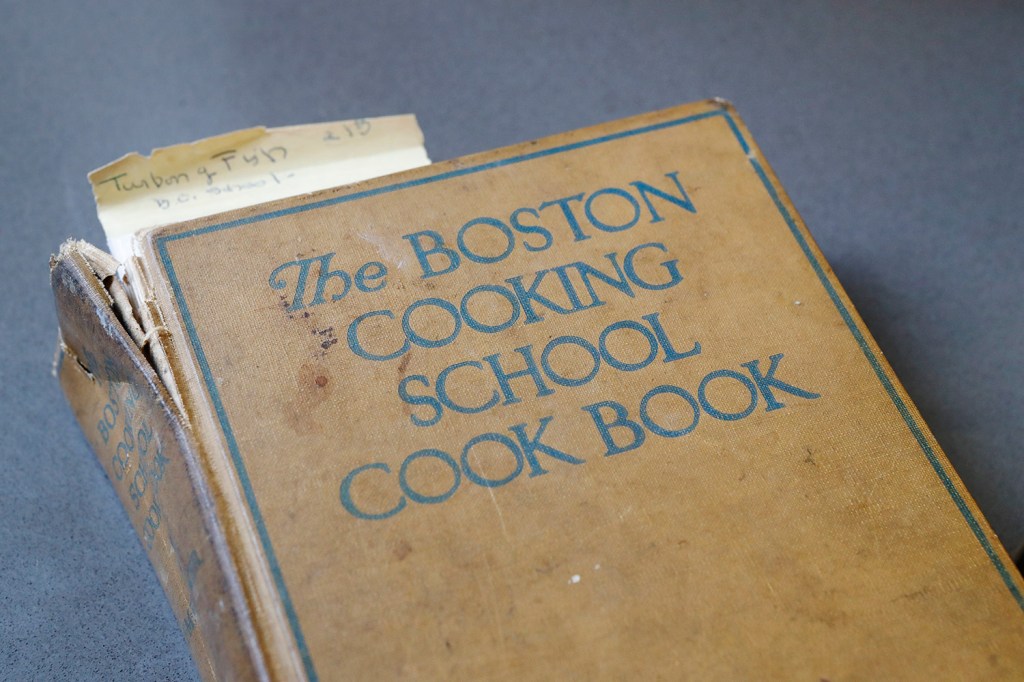

The recipe comes from the 1934 edition of “The Boston Cooking School Cook Book” by Fannie Merritt Farmer, which Knowlton inherited from her grandmother, Dorothy Wellington Britt. The book, stained from decades of use, sits on the kitchen counter at the Inn at Bath, which Knowlton owns, while she cooks.

Knowlton starts explaining the tweaks and shortcuts she’s made to the original recipe, such as substituting bacon for salt pork and adding chopped carrots and celery to give the chowder a little color. Rather than make her own fish stock, she uses canned Bar Harbor brand fish stock, “which is actually good and means you’re not dealing with heads and tails and stuff like that.”

This fish chowder is one of Knowlton’s favorite dishes, but not just because of how it tastes. When Knowlton was a little girl visiting her grandmother in South Dartmouth, Massachusetts, her grandmother always made the chowder to welcome her, serving it from a big pottery urn.

“I loved the ritual of arriving for the weekend and the fish chowder would be on the stove,” Knowlton said.

Later, Knowlton’s mother made the soup in her electric skillet. Knowlton learned how to make the chowder at an early age, taught by her mother and grandmother. But Britt may have learned the recipe straight from the source. Sometime between graduating from the Boston Museum of Fine Arts School and marrying her husband, Albert, a humanities professor, Britt attended Miss Farmer’s School of Cookery in Boston.

MISS FARMER’S PUPIL

Fannie Farmer was born in Boston in 1857 and learned to cook as a teenager. After overseeing her family boarding house for some time, she enrolled in the Boston Cooking School, and eventually she ran the place.

Farmer wrote a lot of cookbooks, but her best known is “The Boston Cooking School Cook Book.” It was an immediate best-seller and has since gone through 13 editions, the most recent in 1990. In the book, Farmer promoted standardized measurements, eliminating such charming but imprecise recipe instructions as a chunk of butter the size of a walnut or a teacupful of sugar.

In 1902, Farmer launched her own school, Miss Farmer’s School of Cookery, which was like a culinary finishing school for young women like Dorothy Wellington Britt.

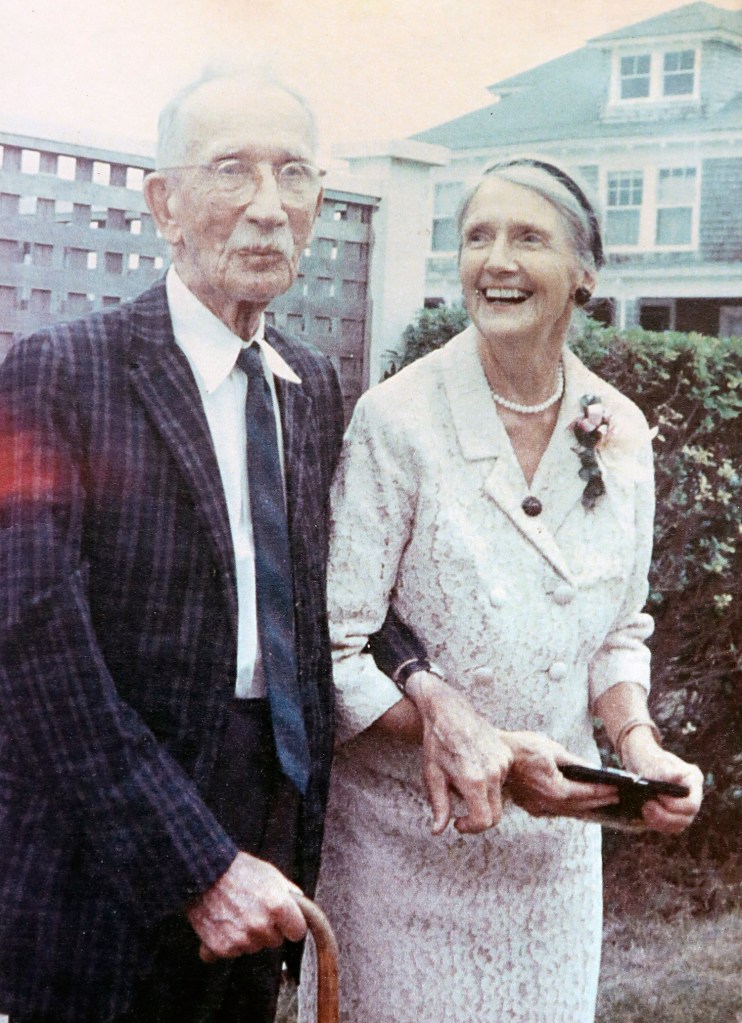

Britt was born in Boston in 1893 and was a proper lady, like her name. She learned how to cook and sew, but dressed casually most of the time in her trademark blue jeans with braided hair wrapped around her head.

“She would have called this Baaath, where we are,” Knowlton said, drawing out her a’s into a long ahhh sound. “She had this great, very Brahmin-y Boston accent, not the typical Boston accent. I lived in Montana, and she called it Mahn-tahn-ah.”

Britt may have had a conservative upbringing, but she held tight to her free spirit. After she married, she lived for a time in New York City, where she became a painter. She sold some of her work, but her bread and butter was an interior design business she founded. After stints in Illinois, where Albert Britt was president of Knox College, and California, where he taught at Scripps College, the couple moved back to Massachusetts.

Once, when her two children were still little, Britt and her husband left them in someone else’s care and went out West to travel on horseback through the Canadian Rockies. “Who does that?” Knowlton said, marveling at her grandmother’s ahead-of-her-time adventures. “Who does that now?”

LIFE IN LETTERS

Britt left behind more than two dozen small, handwritten journals dating back to 1907, most of which now belong to Knowlton. (Every grandchild received the journal from the year of their birth; Knowlton kept the rest.) Most cover a single year, although one details a trip to Italy Britt took as a girl with her Aunt Ella. An entry in 1947 notes she woke up early at 6:30 a.m. to finish some ironing. She kept note of how much she paid for dinners and a corset, and she listed books she read and movies she saw.

Knowlton likes to skim through the diaries occasionally, seeking out historic dates. On Nov. 22, 1963, Britt wrote: “Started cleaning house when Van (a neighbor) phoned. Pres. Kennedy shot! Radio on til dinner while cleaning.”

Knowlton recalls a summer day in the 1970s when she canceled her plans to go to the beach after learning that her grandmother – then about 80 years old – planned to board a bus to Seabrook, New Hampshire, to take part in a nuclear power protest. Knowlton asked to tag along, “and so we hung out together.”

“(Nuclear power) was often a big topic of conversation at our dinner table,” Knowlton said, “so she just went to learn about it. I was blown away that she was doing it.”

When Britt died in 1996 at age 103, her obituary called her “a talented painter as well as an organic gardener and an early promoter of natural foods and vegetarian cooking.”

“She loved vegetable gardening, and she loved to cook,” Knowlton said. “Every night, all summer long, we’d just have stuff out of the garden.”

Britt did not talk about Fannie Farmer’s school much, Knowlton said, but she always referred to the iconic cook as “Miss Farmer.” Britt tucked notes, scribbled in tiny handwriting, into her copy of the cookbook marking her favorite recipes. The notes, which remain in the book, are her shorter, “cheat sheet” versions of Farmer’s recipes, Knowlton said.

One note goes with the lobster bisque, which may well be Knowlton’s least favorite dish of her grandmother’s. Whenever the family ate lobster, Britt would save the “lobster bones” to make bisque.

“She’d start it at 5 in the morning,” Knowlton recalled. “We’d be sound asleep. And the smell of the lobster bones just boiling …”

It wasn’t exactly appetizing at the eggs-and-toast time of day. Plus, she made the bisque with powdered milk and water.

ONIONS WITH ROOTS

Even the smell of fresh beets at a farmers market can bring back memories for Knowlton. Her grandmother and aunt were both avid gardeners who summered in Blue Hill, where Knowlton visited them every year. Both women were acquainted with back-to-the-land gurus Helen and Scott Nearing, who also lived in the area.

“My grandmother got some top onions from the Nearings, and then gave some to my dad, who then gave some to my friend Betsy’s father,” Knowlton said. “Betsy, 10 years after that, moved to Montana, and her dad gave her some from that same batch.”

Betsy’s onions eventually died, but by then she had spread them around to her own friends. About 10 or 15 years later, Betsy was walking through a friend’s garden in Helena and the friend pointed out some of the Nearing top onions. When Betsy’s son returned to Maine to go to college, she sent along some top onions for Knowlton, descendants of that original Nearing plant.

“Isn’t that a great story?” Knowlton said. “So now they’re here. I had them at my house down the street, and when I bought the inn I dug them up and brought them here.”

Just as the onions tied generations of gardeners together, Knowlton’s grandmother was the person who held the family together. Though she was often unconventional, she also loved and protected her family “like a mother bear,” Knowlton said.

“She was a real solid person in all of our lives,” Knowlton said. “She was glue for the family in many ways. Not matriarchal so much, but she was totally predictable all the time. You knew she would be there for you.”

After Britt died, Knowlton asked for the cookbook, both for sentimental reasons and because she wanted it for her cookbook collection. Britt kept most of her recipes on note cards, which were claimed by one of Knowlton’s sisters.

Knowlton returns to “The Boston Cooking School Cook Book” for basic recipes, which she then plays with in her own kitchen, as she has with the fish chowder, her favorite from the book and one she says has held up well.

“My sisters and I all make it now, and we’ve worked on the adaptations of it,” including a pesco-vegetarian version, Knowlton said. “We make it without the bacon and with olive oil. Leeks instead of a lot of onions.”

But her love of the book goes much deeper than a single recipe. The fact that she can still hold something that her grandmother held, and see her distinctive handwriting in the notes she tucked into its pages, is priceless.

Send questions/comments to the editors.