Teller Marina Moulton wasn’t interested when her employer, Norway Savings Bank, brought a health coach into her branch in South Portland.

“I really love my M&Ms,” she explained.

But a recurring problem with her left hip wasn’t responding to repeated trips to a chiropractor and other health care providers. So Moulton decided she’d give the bank’s workplace wellness program a chance and met with an on-site health coach, one of the many services offered in the bank’s program.

The coach recommended yoga to improve her hip’s range of motion.

Moulton, 46, signed up for a yoga class in Scarborough and now nearly a year later, her hip is unstuck and Moulton is 57 pounds lighter.

“Having that health coach kept me accountable,” said Moulton. “We talked about our goals – there’s a lot of heart disease in my family – and I learned healthy eating habits and portion control. It’s made a huge difference.”

Moulton is just one of the thousands of Maine employees participating in their employers’ workplace wellness programs. Most of the initiatives were started first as a means to control health care costs, but are now touted for lifting morale, improving productivity, cutting down on absenteeism and supporting healthier employees.

“Initially we considered these programs when we were faced with escalating health care expenses,” said Richelle Wallace, senior vice president of human resources at Norway Savings Bank, which has been recognized nationally for its workplace wellness program. “Then we realized all the other benefits. Healthier employees are happier employees.”

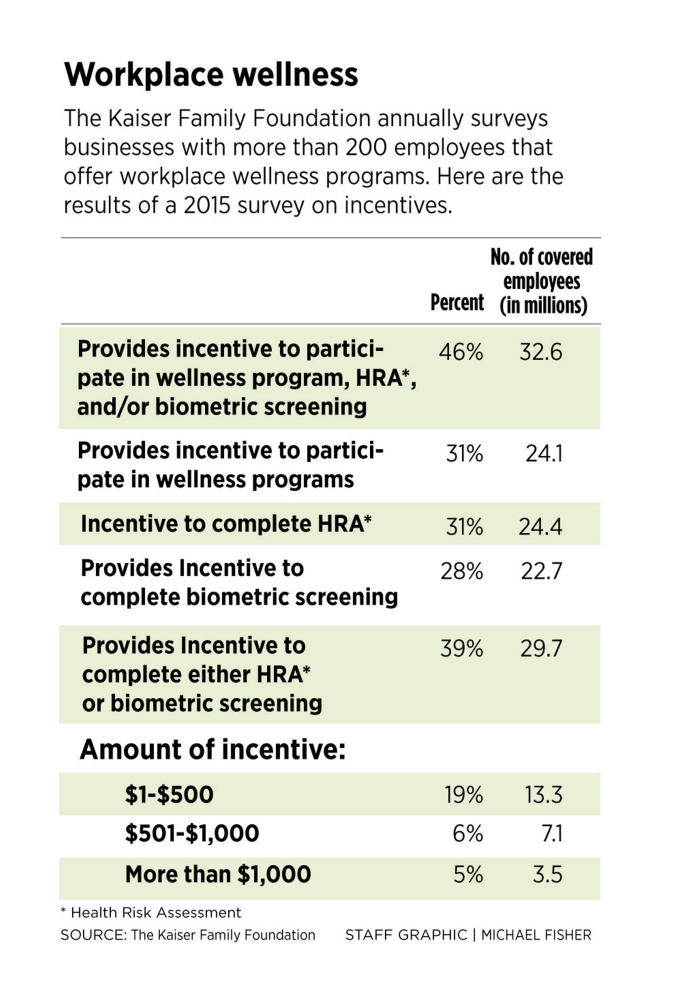

A growing number of American businesses are seeing the value of workplace wellness programs. According to an annual survey conducted by the Kaiser Family Foundation and the Health Research Annual Trust, 50 percent of firms offering health benefits in 2015 offered wellness programs related to tobacco cessation, weight loss and/or other lifestyle or behavioral coaching, up from about 27 percent in 2005.

Large firms of 200 or more employees were more likely to offer such wellness programs than smaller firms (81 percent vs. 49 percent). Also, an increasing percentage of companies offer incentives to boost participation rates, such as making contributions to a health savings account or awarding gift cards.

Norway Savings does both. Twice a year, employees are offered incentives to participate. In one program, the employee sets a goal – “It can be eating one less Little Debbie a week – you don’t have to train for a marathon,” said Wallace, and a health savings account incentive is triggered when the goal is reached.

There’s also a separate performance-based incentive based on biometrics such as blood pressure readings, cholesterol measures and blood sugar levels. An employee sets five goals and if she meets four of them in a year, she gets a $100 gift card.

Ninety-eight percent of the bank’s 288 employees participate in the program, said Wallace.

Marina Moulton of Scarborough, background, takes a yin yoga class with instructor Emily Marcus, foreground. Moulton’s doctor recommended yoga when she developed hip problems. Since then Moulton has increased her mobility and lost 57 pounds.

HEALTHIER WORKERS

Duratherm Window Corp., a window-maker in Vassalboro, has a similar story to tell. A letter from its labor attorney suggested the company consider a workplace program as a means to control health care costs. It also blended nicely with an existing company safety initiative.

But CEO Tim Downing said it took a while for the company to decide what type of program to offer employees, since so many of them focused just on fitness. The company wanted something with a holistic approach to wellness, said Downing, with an emphasis on personal contentment goals.

The company contracted with Occupational Medical Consulting of Leeds, which provided an on-site health coach to meet with employees one-on-one to develop personal goals. People receive wellness scores based on 14 risk assessment measures, which are updated periodically. The aggregate performance is shared with the company twice a year.

In the six and half years Duratherm has offered a wellness program, it has seen significant drops in body mass index readings of its workforce, reduced the numbers of smokers and increased what Downing calls “presenteeism” – a more engaged workforce that calls in sick less often and seems to be more productive when they are at work.

The program also helped to adjust the workplace mindset around aging – an issue the company is especially sensitive to since the average age of its 65 workers is roughly 52.

“A lot of the risk factors associated with aging such as weight gain, high blood pressure, hypertension, are things people characterize as ‘It just happens with age.’ ” said Downing. “But because we have a high participation in our wellness program – about 93 percent – we can demonstrate that those risks associated with aging can be improved in an aging population.”

For instance, the company’s collective BMI was high two years ago and employees wanted to bring that down to normal. Downing said the health coach emphasized that people should avoid yo-yo dieting at all costs, which can do more long-term harm than good in a weight loss program. So employees set a baseline weight and were weighed every week, with progress checks every quarter.

They were awarded “duracoins” – the company’s incentive that can be redeemed for money or prizes – for every week they maintained or lost weight.

Now, two years later, the workers lost 150 pounds as a group and the company’s collective BMI is in a healthy range, said Downing.

“That’s what we need to look at as an employer, you have to maintain your employees and to do that, you have to look at their well-being,” said Downing. “The wellness program is an opportunity to overcome these foreboding trends in the labor market.”

Among the company’s biggest proponents of the workplace wellness program is Andy Bourassa, a production worker who eight years ago weighed 431 pounds.

His doctor had encouraged him to consider bypass surgery to lose weight, but Bourassa said he avoided it because he kept thinking he could lose the weight himself.

But conversations with Duratherm health coach Eric Gordon convinced Bourassa that he should explore bariatric surgery, which he had in August 2014. Now he weighs 226 pounds.

“The big thing was setting goals for myself,” said Bourassa, 48, who participated in the Tough Mudder obstacle course race last year and the Trek Across Maine bike ride. He still collects his duracoins each quarter for achieving his goals, which he’s redeemed for gift cards to Hannaford and items from L.L. Bean.

“The biggest thing has been the improvement in my quality of life,” he said. “Before, I’d get home and my knees would hurt so bad all I could do was sit down and do nothing.”

Now he’s going to dances, riding in fundraisers and enjoying activities with his family.

Moulton, too, is enjoying her active lifestyle, almost to the point where she doesn’t miss her M&Ms. Her enthusiasm has inspired two co-workers who now join her in yoga classes.

“They knew about my hip thing and kept telling me I was too young for hip replacement surgery,” said Moulton. “I told them they have to try yoga. Now we all go.” q

Send questions/comments to the editors.