The University of Maine has regained its position as a top national competitor to develop a technology for offshore wind power and create a new clean energy industry.

An experimental turbine being developed by a UMaine-led consortium for use in a floating, deep-water wind farm was chosen Friday as a finalist in the Department of Energy’s Offshore Wind Advanced Technology Demonstration program.

The UMaine consortium had been one of several competitors for the three $40 million grants to be awarded by the energy department, but it lost ground to other projects in earlier rounds of funding and was designated as an alternate proposal.

Friday’s announcement means that Maine’s project, known as the New England Aqua Ventus I offshore wind pilot project, will be one of up to three leading projects that are each eligible for up to $40 million in grant funding over three years for the construction phase of the demonstration program.

“This decision is outstanding news for Maine and a testament to the unmatched hard work and ingenuity of the University of Maine and the numerous Aqua Ventus partners,” Maine Sens. Susan Collins and Angus King said in a joint statement Friday. “We applaud them for their efforts and will continue to support them as they strive to lead our state and nation into a brighter, cleaner energy future.”

UMaine President Susan J. Hunter described the decision as a historic opportunity for Maine and New England.

“The level of research and development by UMaine researchers, students and partners that helped make the New England Aqua Ventus project a reality demonstrates the distinction of a public research university – and the difference it can make in its state, region and beyond,” Hunter said.

The Maine project had been competing with demonstration proposals in other states for a demonstration program grant, but was passed over in 2014 in favor of ventures in New Jersey, Virginia and Oregon. Instead, Maine became an alternate, and got $3 million to continue engineering and design work.

The Energy Department wants the United States to develop an offshore wind industry because roughly 80 percent of power demand occurs in coastal states. Europe has hundreds of offshore wind turbines, mostly in shallow water on steel towers buried in the seabed.

The Obama administration is seeking new designs to radically cut the cost of wind energy. One idea is to have turbines that float far offshore, where the wind is stronger and steadier, and where people can’t see or hear them.

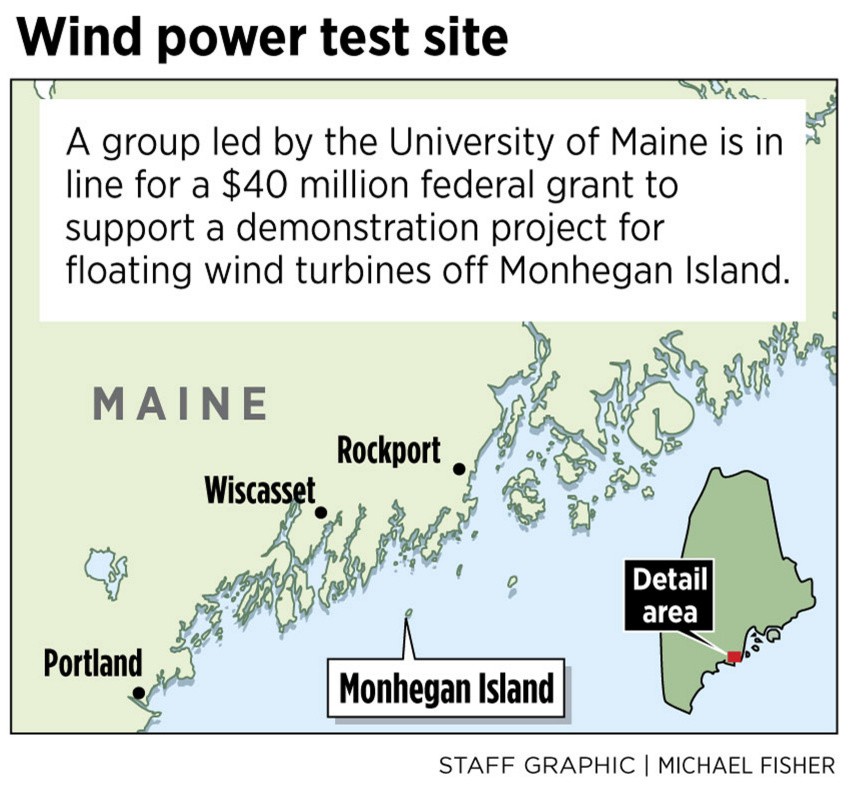

But things haven’t gone as planned. Each of the three winners has been unable to secure a power purchase agreement for electric output. Last November, the Department of Energy gave the projects six-month extensions to try to resolve their problems. At the same time, Maine won $3.7 million to further refine its proposal, which would be located off Monhegan Island.

Six months later, the Oregon and Virginia projects are being dropped from the program and Maine Aqua Ventus is being elevated to a demonstration project, alongside the Fishermen’s Energy project in New Jersey and the Lake Erie Energy Development Corp. project, which also had been an alternate for demonstration project funding.

Maine supporters had been waiting to hear if the Energy Department would give up on any of the initial winning bids and whether it had concluded that Aqua Ventus has a better chance of coming to fruition. The project won a 20-year power-purchase agreement from the Maine Public Utilities Commission. An average Central Maine Power Co. home customer would pay an additional 73 cents a month, or $8.70 in the first year.

Maine Aqua Ventus is being developed by a for-profit spinoff that represents UMaine, Cianbro Corp. and Emera Inc. of Nova Scotia. The proposal is unique in that it’s made from advanced composite materials instead of steel, to fight corrosion and reduce weight. The hull is concrete, which, unlike steel, can be produced in Maine.

In 2013, the partners launched a one-eighth scale model and tested it off Castine. The pilot project would be full size, consisting of two turbines with a capacity of six megawatts, enough to power 6,000 average homes.

“The Aqua Ventus project represents a tremendous opportunity for the state to capitalize on our advanced and highly skilled workforce paired with our clean-energy ambitions,” said Jeremy Payne, executive director of the Maine Renewable Energy Association. “This project brings together the best of all three worlds: economic growth and innovation; emission-free electricity; and Maine-made secure energy.”

If the pilot programs are successful, supporters envision hundreds of offshore wind farms nationwide and jobs for hundreds, perhaps thousands, of workers to install and maintain the turbines.

Clean-energy advocates see Aqua Ventus as Maine’s only near-term chance of developing an offshore wind industry.

In 2011, the Norwegian energy giant Statoil proposed an experimental, $120 million floating wind farm off Boothbay Harbor. But the company left Maine after a political maneuver by Gov. Paul LePage in 2013, and instead went to Scotland. Last week, Statoil announced plans to build the world’s largest floating wind farm involving five turbines off the Scottish coast.

Closer to Maine, other states have emerged as research and development centers for the evolving technology. In Rhode Island, Deepwater Wind began laying undersea cable this month to towers at its 30-megawatt Block Island Wind Farm, the country’s first offshore wind farm.

Even with a federal grant, the Maine project still needs to attract more than $100 million in private investment.

It also will seek to gain support on Monhegan Island, where at least some summer and year-round residents are concerned about the visual impact of the project and its potential interference with lobster fishing.

The turbines will be anchored 2.5 miles off the island’s southern tip and roughly 10 miles off the mainland. With turbine hubs 350 feet above the water and blade tips reaching 600 feet into the sky, the project would be visible from some locations, but not from the village, according to Jake Ward, vice president of innovation and economic development at UMaine.

Ward was on the island this week, meeting with a task force formed by the plantation. A citizen group, the Monhegan Energy Action Coalition, also has come together to question the scale of the project and the impact of an undersea cable.

“Some people like it, some don’t,” Ward said. “Like any group, there are people on all sides.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.