In most of Maine, adults who want to make their living trapping lobster must wait until a licensed lobsterman dies or forgets to file a license renewal.

There is only one place in the state, in the waters of eastern Penobscot Bay off Stonington, Vinalhaven and Isle au Haut, where a resident who completes the necessary training and safety classes can get a license to lobster without waiting for at least a decade. But the lobstermen who oversee Maine’s last open lobster territory are now fighting over whether to cap the number of lobstermen who can fish those waters, effectively closing the last open door to the state’s largest commercial fishery.

The debate is pitting islanders who worry that a cap would eliminate an incentive for adult children to return home against mainland fishermen who want to protect this lucrative industry from outside exploitation. After years of debate, the local lobster council has tried to put the issue to a vote twice before, but the meetings have fallen through, with members missing meetings or walking out moments before a closure vote could be held.

The council was scheduled to try again this week, at a meeting where zone closure was the only topic on the agenda, but had to cancel because it lacked the quorum needed for a legal vote. One councilor had other plans. Another councilor had a family emergency. But two island-based councilors told the state Department of Marine Resources they wouldn’t be coming to a meeting as long as zone closure remained on the table.

“Feelings are running really high,” said Sarah Cotnair, the state liaison to the state’s seven lobster councils. “A lot of the lobstermen want to close the zone. They don’t want to share the bay with people from away, who come up from Scarborough or Boothbay just to lobster. Those who want to keep it open, they say an open zone is good for jobs, good for the local economy, especially for the islands. It’s a fight that’s been going on for years.”

ENTRY DIFFICULT IN MANY ZONES

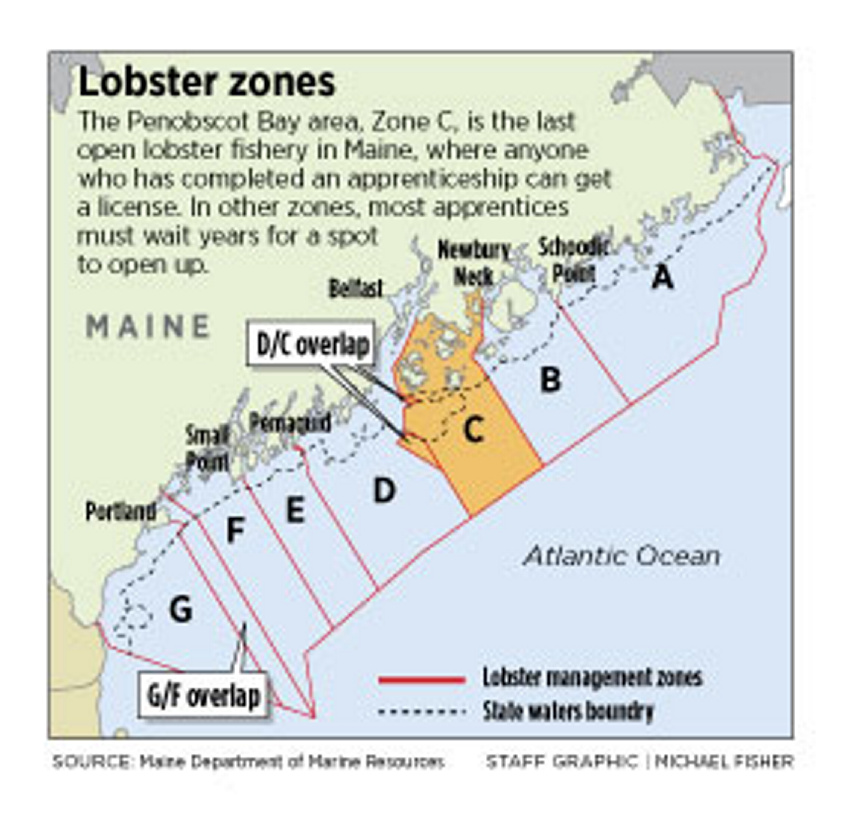

The coastal waters of Maine are divided into seven fishing zones, lettered A through G, that stretch from the border with the Canadian Maritimes down to the New Hampshire state line. Lobstermen must complete 2,000 hours of training over 200 days, or two lobster seasons, as an apprentice to a licensed lobsterman from the zone where they live and will fish before they can apply for a state license. In all but eastern Penobscot Bay, or Zone C, apprentices wait for years for a spot to open up.

Maine has 7,280 licensed lobstermen, each assigned to a zone based on their home address, but not all of them are traditional commercial fishermen who set a full run of 800 traps and may employ a sternman or two. One out of four is a recreational fishermen. One in seven is an apprentice or a student. One in 14 is over the age of 70, holding on to the state license to keep a connection to lobstering or to enable an unlicensed relative to keep fishing.

State statistics show that about a thousand of those license holders don’t land a single lobster in a typical year.

Although the fishing community talks about this debate in terms of open or closed, the issue boils down to entrance limitations so strict that people on the waiting list often feel like the zone is simply closed. People can get licenses in a “closed” zone, but they must wait for a spot to open up. In most cases, a spot only becomes available when someone has moved, died or forgotten to renew their license, Cotnair said. Most zones require more than one license-holder to leave before someone new can come in.

And some zones cap the number of lobster traps allowed in the zone rather than the number of lobstermen, since not everyone fishes a full run of 800.

No lobster zone, regardless of how crowded, is closed to a student who has completed a 2,000-hour apprenticeship and gets a high school diploma, or its equivalent, by age 20. A state law adopted in April gave these students more time to put in their hours, giving them two extra years to complete their apprenticeships. Lawmakers and fishermen hailed it as helping to keep the lobstering tradition alive among the upcoming generation of fishermen.

Although it is open, the number of licensed lobstermen in Zone C fell from 904 in 2014 to 830 in 2015, the lowest level since before 1997, when the state’s marine resources zone data was first collected. The number of apprentices, students and those who lobster for fun also fell over the past year, statistics show, lower than only a few years in that same 19-year time span.

BIG DECISION, LONG PROCESS

If the Zone C lobster council ever initiates the process to limit entry, it also would have to set a ratio of how many licenses or traps must become available before someone new can come in. Once that ratio is set, they would send out a survey to all licensed lobstermen in their zone to weigh in on closure and the proposed ratio. The council does not have to abide by the survey results, but most have done so, Cotnair said.

The council’s proposed change then goes to the Lobster Advisory Council and the state’s marine resources commissioner for review.

“If there is a vote (on closing Zone C), it will be very close,” said council member and state Rep. Walter Kumiega of Deer Isle, who chairs the Legislature’s Marine Resources Committee. “My hope is if the zone closes, it will have a 1-to-1 or 2-to-1 exit ratio so there will still be reasonable entry. … It is a very big issue. It puts fishermen dealing with very crowded conditions on the water in conflict with a need to allow entry to maintain the population of their communities.”

The last lobster fishery to close in Maine was Zone A, the Bold Coast region that borders the Canadian Maritimes. John Drouin of Cutler, a licensed lobsterman for 37 years, was chairman of the council in 2004 when it voted to close, and still heads up the board today. The closure process there was difficult and slow, stretching out over a three-year period, Drouin said. He held public hearings in every district of the zone to help the council assess the community’s wishes.

“This issue isn’t on the shoulders of the council, it is up to the fishery participants,” he said. “So it was easy for me to vote in favor of closing since the vote in my district was like 72 percent in favor of closing. … You can’t please everyone, but as a representative, you can please the majority of who vote. And that is where you, as a council member, have to leave it. If they don’t have the stomach for it, then they shouldn’t be on the council.”

DIVISIONS KEEP THE STATUS QUO

The Zone C council sent out an unofficial questionnaire to license holders in 2015 that showed a majority wanted to limit entry to the fishery. Some members, such as Chairman Michael Sherman of Brooklin, whose district voted 45-10 in favor of closing the fishery, pointed to those results to explain why they support closure. But members who represent the island communities of North Haven and Isle au Haut want to keep it open.

The council voted in March on whether to keep the fishery open, but it failed along mainland-island lines. Island members walked out before a second vote that would have effectively closed the fishery for at least a year could occur.

Cotnair said the council hasn’t been able to corral the number of members needed to even hold a legal vote on the matter since.

Send questions/comments to the editors.