CUMBERLAND — Town officials in Cumberland plan to spray pesticides to slow down an infestation of browntail moths that is expected to cause skin rashes and respiratory problems in more than a dozen communities this summer.

They intend to spray the pesticides along a 3-mile stretch of Foreside Road within the next few weeks to kill browntail moth caterpillars just as they come out of their winter cocoons and begin to feed on new leaves.

The invasive species can cause physical problems for humans and defoliate native hardwood trees. State scientists warn that the species is more abundant than it has been in a decade. Cumberland officials hope that confronting the moths now could limit the impact by preventing the infestation from spreading farther into town.

“It’s almost like a fire line … to keep them from marching inland,” said Town Manager William Shane.

For the spraying to be effective, however, the town needs Cumberland Foreside homeowners to allow its contractor to spray onto their properties. Most residents appear to be on board with the program, although some people are uncomfortable with using a pesticide treatment, officials said.

“I am not 100 percent for spraying, but when it comes to this, there is no alternative,” said Tom Gruber, a town councilor who has lived on Foreside Road for more than 30 years.

“The more residents that opt in for spraying, the more likely the chances are that we can stop this invasion,” Gruber said.

A COASTAL PROBLEM MOVES INLAND

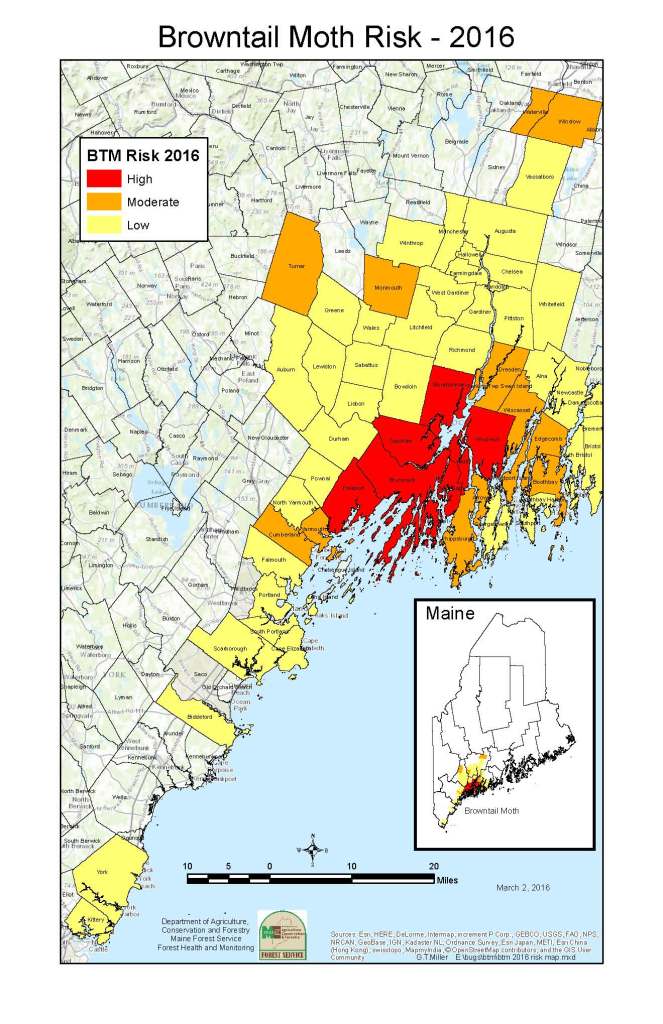

Cumberland is the only community planning to address the issue with pesticides, although it is only one of more than a dozen towns and cities at risk of moths this year, according to the Maine Forest Service.

Coastal communities north and south of Portland and as far east as Boothbay are at moderate risk of moths. The epicenter of the high-risk area is between Freeport, Harpswell, Woolwich and Bowdoinham. Although moths have typically been a coastal problem, the population during this outbreak stretches as far inland as Turner, Waterville and Winslow.

Browntail moths were introduced to the U.S. more than 150 years ago, and are usually located only in coastal southern Maine and on Cape Cod. The population tends to stay at a low-enough level that it isn’t a problem, but periodic infestations can last for years and spread far from coastal areas, said Charlene Donahue, a forest service entomologist.

The reason for population surges is poorly understood because there is no good scientific research on the moths. Visual surveys of winter webs in the past two years suggest that the current infestation is the worst in more than a decade, Donahue said.

Moth caterpillars nest by the hundreds in winter webs, clusters that look like bunches of dead leaves often located in oak and apple trees. Seriously affected areas can have tens of thousands of webs. An aerial survey of infested areas last fall showed serious defoliation in trees that were starting to shed their leaves, caused by tiny caterpillars before they nest for the winter, Donahue said.

“I was shocked to see how much damage there was in the fall,” she said. “We haven’t seen that kind of damage in 15 years or so.”

TOXIC HAIRS HAVE STAYING POWER

Browntail moths harm trees, but the leading concern is the health effects they have on humans.

The caterpillars are covered in microscopic poisonous hairs that cause a severe rash similar to poison ivy and can lead to respiratory problems for some people. Caterpillars will shed the poisonous skin five times over the spring. The hairs drift around, and can get on exposed skin and even saturate clothing drying outside. The toxins in the hairs take up to three years to break down, which means they stay in the environment and affect people months after caterpillars are gone, Donahue said.

“Just being in the area can give you a rash,” she said.

The outbreak 15 years ago was so severe that some coastal communities coordinated a regional aerial pesticide spray to cut back the insect population. That program became controversial, partially because of concern that widespread use of pesticides could harm lobsters and other shellfish. The infestation was finally tempered by several years of wet, cool springs that produced a tree fungus that decimated the moth population. Without a similar fungus, the infestation could continue for years, Donahue said.

Targeted pesticide spraying such as the effort in Cumberland can limit moths locally, but won’t have an impact on the broader problem, Donahue said.

“Realistically, what this mostly will provide is relief from the rash. It is doubtful it will really suppress the population,” she said.

TIMING, STRATEGY FOR SPRAYING

Cumberland plans to use truck-mounted sprays to treat areas between 250 and 500 feet in from Foreside Road. Terry Traver, a licensed pesticide applicator with Whitney Tree Service, said the chemical his company uses, Tempo, is approved by the state, but he appreciates that some people may be uncomfortable with spraying an area with chemicals. Whitney is the company the town is contracting with to spray.

“We’re just trying to suppress it in some of the public areas,” Traver said.

The pesticide is only effective when caterpillars are feeding on treated leaves, so that means the treatment has to be applied in the next few weeks, just as caterpillars are breaking out of their winter webs.

That leaves the town with only a couple of weeks to get the buy-in from Foreside residents to spray as much of the area as it can. The Town Council will hold a workshop at the town office at 6 p.m. Monday to explain the program to residents.

Send questions/comments to the editors.