AUGUSTA – State health regulators heard conflicting testimony Tuesday on a controversial and apparently unprecedented proposal to make opioid addiction a condition that qualifies for treatment with medical marijuana.

The 3½-hour hearing before the Maine Department of Health and Human Services was sought by medical marijuana caregivers, who believe the drug can help people stay off opioids and deal with withdrawal symptoms.

But medical doctors and other health care providers strongly oppose the proposal, saying there is little or no scientific evidence to support the use of marijuana for such purposes, and that doing so could create another drug dependency for addicts.

The use of medical marijuana was approved by Maine voters in 2009 and about a dozen conditions qualify for a prescription, including cancer, AIDS and seizure disorders.

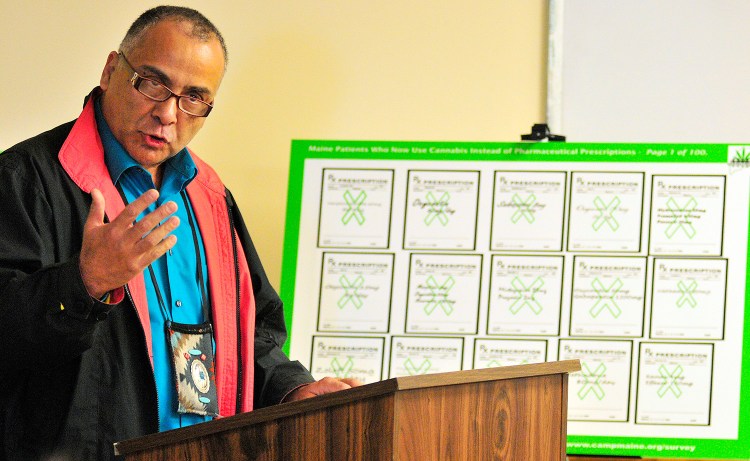

Maine is the first state to formally consider allowing medical marijuana to be used as treatment for addiction to opioids, said Dawson Julia, a caregiver from Unity who submitted a petition to request the hearing.

Julia said that cannabinoids prevent people from building up a tolerance to opioids, so they don’t require increased painkiller dosages, and that medical marijuana can help relieve opioid withdrawal symptoms. Typical withdrawal symptoms include nausea, diarrhea, muscle spasms, insomnia and anxiety.

Catherine Lewis of Medical Marijuana Caregivers of Maine spoke in favor of the proposal. She recounted her own experience of using medical marijuana to help her through opioid withdrawal, and then continuing to use it to treat chronic pain from a car accident.

“Instead of being a gateway drug, it is an exit strategy for so many people,” she said of marijuana.

EMOTIONAL STORIES

Another proponent was Matthew Low of Waterville. He testified that he was caught in a cycle of addiction: He’d quit heroin, start methadone treatment, then relapse and repeat the cycle.

Then he tried medical cannabis.

He said he used medical marijuana oil and concentrates to ease withdrawal symptoms during detox, and now uses medical marijuana to keep his cravings for opioids at bay.

“The cravings stay away longer every time I use cannabis,” he said. “The (methadone) clinics aren’t helping. They’re treating, not curing. I believe cannabis can cure this epidemic.”

Low, who has been sober for nearly four months, was among the nearly 30 people – including four doctors – who asked state regulators to approve the proposal. Four people representing medical groups and the substance abuse prevention community spoke in opposition.

Leah Bauer, a psychiatrist speaking on behalf of the Maine Association of Psychiatric Physicians, said the organization is strongly opposed to adding opioid addiction as a qualifying condition because there is no evidence that marijuana is helpful in treating addiction. She said marijuana does not help with withdrawal symptoms and is addictive for some patients.

“Marijuana may be throwing gasoline on the fire,” Bauer said.

In 2014, 350,000 Mainers – about one in four residents – were prescribed a total of 80 million doses of opioid medication, according to the DHHS, and overprescription of opiod painkillers is believed to be a factor in the growing heroin crisis in Maine and elsewhere. The heroin epidemic has fed a spike in drug overdoses, which claimed the lives of 272 Mainers last year, up from 208 in 2014 and 155 in 2011.

Julia says researchers have found that opioid overdose death rates are 25 percent lower in states with medical marijuana laws.

Throughout the hearing, medical marijuana patients told emotional stories about battling addictions to strong painkillers and losing friends to overdoses. They challenged state regulators to consider allowing medical marijuana as a treatment for opioid addiction, despite a lack of medical research because of marijuana’s status as a Schedule I drug.

“This is Mainers trying to help other Mainers,” said longtime advocate Will Neils. “A visionary move on your part could save lives.”

The four physicians who testified in favor of the petition were Dustin Sulak, Eric Mitchell, William Ortiz and James Li.

“While I am not aware of any rigorous medical literature that quantitatively measures the effectiveness of medical marijuana therapy as a therapy for reducing opiate dependency, I can say over three years of my own certification practice that we have had hundreds of patients attest to the effectiveness of this process,” said Li, an emergency room physician with a part-time private practice, in written testimony. “Indeed, seeing high-dose opiate patients eliminate all use of opiates within a year of certification for medical marijuana use has been a major incentive for me to continue my certification practice.”

SCIENTIFIC SUPPORT QUESTIONED

Representatives of the Maine Medical Association spoke against the petition, citing concerns about a lack of medical research and substituting one substance for another when treating addicts.

Heath Myers, overdose prevention specialist for the city of Bangor, said the proposal confuses psychological addiction with physical dependence on opioids. He said he has “strong reservations” about considering marijuana as a treatment for drug addiction and believes that the people behind the petition are “asking Maine to embark on an experiment the best medical science does not support.”

The number of medical marijuana patients has grown in recent years as patients have looked for alternatives to opioid painkillers, advocates say. The state cannot provide an exact number of patients because it does not keep a registry, but doctors in 2015 printed more than 35,000 certificates required under state regulations to certify medical marijuana patients. That number could include duplicates and replacement certificates and is likely higher than the actual number of patients, according to the DHHS. About 300 doctors across the state certified patients in 2015.

DHHS Commissioner Mary Mayhew has 180 days to approve or deny the petition. Under state law, she can consider public testimony and written comments, and consult with physicians and seek more research at her discretion. Written comments will be accepted through May 3.

Send questions/comments to the editors.