Jean Lavallée said he once watched a Canadian lobsterman overstuff a crate with lobsters, put the wooden lid on top and then smash it down with his foot.

The resulting crunch of limbs and shells “sounded like a bowl of Rice Krispies,” he told a group of Maine lobstermen in Bath on Monday. Not only did the carelessness cause needless death and injury, Lavallée said, it also undoubtedly cost the lobsterman some money.

“I couldn’t believe it,” he said.

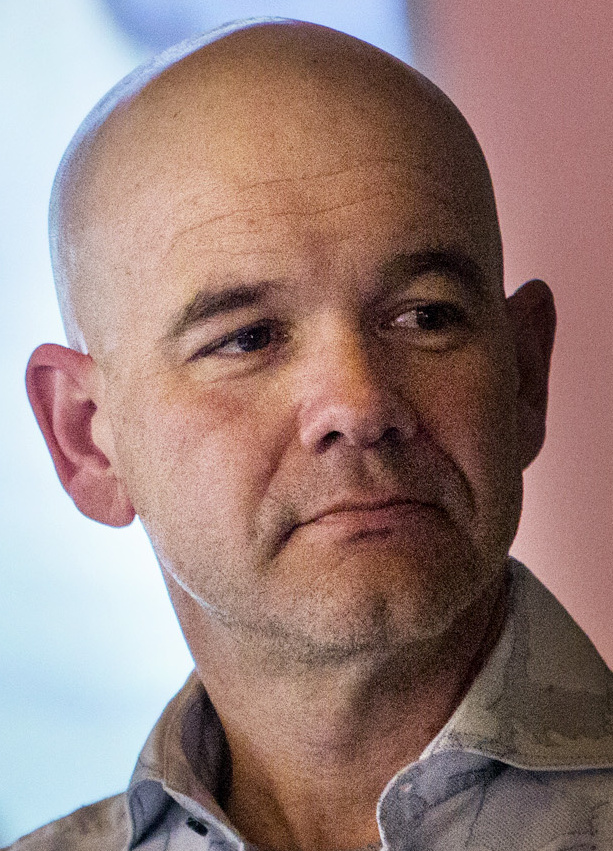

Lavallée, a veterinarian from Prince Edward Island who has specialized in lobsters for more than 20 years, is traveling along the Maine coast this week to lead a series of workshops on proper care and handling of the lucrative crustaceans. The workshops are sponsored by the Maine Lobstermen’s Association and the Maine Lobstermen’s Community Alliance with funding from the Island Institute.

Lavallée said as many as 10 percent of the lobsters harvested in the U.S. die on their way to market. Given Maine’s $616.5 million harvest in 2015, that’s up to $61.7 million in lost revenue for the state’s top fishery.

“We kill more lobsters (prematurely) than most other countries are fishing for their entire year,” he said of the U.S. lobster industry. “That’s a lot of lobsters.”

Lavallée argues that more careful handling of lobsters, based on a better understanding of their anatomy and biology, will reduce losses and save the industry millions of dollars.

FRAGILE CREATURES

Lobster anatomy is so bizarre that minor injury to a spot that would be relatively benign for most other animals can cause instant paralysis or death, he said. For example, a lobster’s nerve cord runs down its belly, Lavallée said. Even a small nick can sever the cord, resulting in paralysis and eventual death.

Even more strange is the location of a lobster’s heart, which is on its back, he said. Not knowing that fact may lead to careless handling that fails to protect the organ.

“If you poke a hole right in the middle (of the back), you’re going to hit the heart,” Lavallée said.

Nonfatal lobster injuries also can be costly to the industry, he said. Practices such as tossing lobsters, handling traps roughly and overstuffing, dropping or banging crates can increase limb loss and bleeding, which reduce the weight and quality of a harvest, thus lowering the sale price.

Lavallée offered a list of simple recommendations such as “one hand, one lobster” when handling the creatures, and treating lobsters as if they were as fragile as eggs.

“It doesn’t take a lot of money,” he said. “It doesn’t take a lot of time. It’s not rocket science. Just do it.”

Another major cause of premature lobster death is stress, Lavallée said. Every step in the lobster harvesting process can cause the release of stress hormones, which can snowball. That includes rapid hauling to the surface, removal from traps, packaging, transport and holding, he said.

Improper holding in live tanks can exacerbate a lobster’s stress, Lavallée said. Potential stressors include temperature shifts, low oxygen levels, exposure to high ammonia levels or other dissolved toxins, changes in salinity, crowding, aggression and even cannibalism.

“It’s like the death by 1,000 cuts,” he said.

Lobsters can live for days out of water if their highly absorbent gills are wet, Lavallée said. However, they cannot flush out natural toxins including ammonia, causing an internal buildup.

Once placed in a tank, the lobster quickly expels its built-up ammonia into the water. Lavallée recommended placing the out-of-water lobsters into one tank to purge their ammonia, then moving them to another, clean tank for holding.

Long-term exposure to fresh water is also fatal to lobsters, he said, adding that even brief contact with rain can cause severe illness. Another mistake some lobster handlers make is packing the crustaceans in a manner that allows their gills to come into contact with freshwater ice, Lavallée said.

“Lobsters don’t do well in fresh water,” he said. “They’re going to die very quickly.”

Other simple practices that Lavallée said help reduce lobster injury and death include hauling traps slowly, bringing them over the rail as smoothly as possible, putting lobsters into crates upright and pointing in the same direction, and using cushioned, cool and moist stations for banding. He cited a 2012 study conducted in Stonington that found such practices reduced injuries by 70 percent and improved the overall quality of the harvest.

“You’ll make more money if you can keep the whole lobster intact,” Lavallée said.

Orr’s Island lobsterman Herman Coombs, who attended the Bath workshop, said Lavallée’s presentation was “eye-opening,” and said he was stepping up his safe-handling practices.

“I never would have imagined that a lobster getting poked in the tail, you could actually paralyze that lobster,” he said.

The Maine Lobstermen’s Association will hold workshops in various Maine locations through Thursday. For more information, go to mainelobstermen.org or call 967-4555.

Send questions/comments to the editors.