A collaboration between Sebago Brewing and Liquid Riot Bottling has produced at least some of the results you would expect from a pair of breweries. There is, after all, a light-brown liquid in a 12-ounce bottle.

Then things get weird.

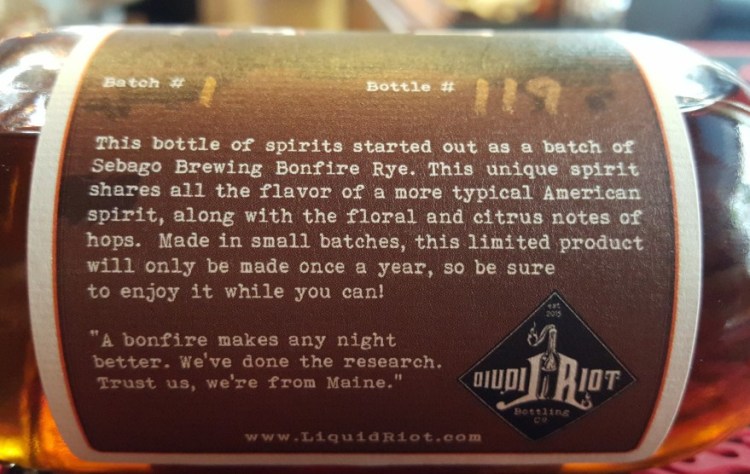

Inside the bottle is 90 proof liquor. Liquid Riot distilled some leftover Sebago beer to produce a whiskey-like liquor, which will be available in limited quantities later this month. The caramel-colored Bonfire Spirit can’t be labeled a whiskey because it doesn’t meet the federal definition of whiskey. Not that your taste buds will know the difference.

Maine brewers collaborate on everything, so distilling beer into whiskey seems like a natural offshoot. Brewers work together on beers, they help each other set up their breweries, and they even collaborate with beer bars to make special one-off creations. The trend, brewers say, is a little about business and a lot about Maine’s collaborative culture.

“From a business standpoint, we’re looking to grow our brand and get some recognition. So it makes sense to work with somebody else who’s going to get recognition and point people your way. So that’s straight business,” Liquid Riot co-founder Eric Michaud said. “But for me and for us, business is secondary. Foremost for us, this is our passion, this is fun and this is what we’re interested in.”

Collaborating is second nature to Michaud and his brother, Ian, who started the brewpub and distillery in 2013. A worldwide beer festival was held in Portland shortly after they opened, which resulted in myriad Liquid Riot collaborations with brewers from Spain, Belgium and Norway.

“We learned from them in three months what would have taken three years to learn. Lots of creativity,” Eric Michaud said. “With the Norwegian guy, we went and cut juniper bows from my family’s property in Falmouth. We wouldn’t have necessarily thought of that without him.”

Two of Liquid Riot’s regularly available beers started as one-off collaborations. Headstash, an IPA originally brewed with Oxbow two years ago, “just kind of took off,” Ian Michaud said. Sour Trouble, a Belgian sour beer, was originally brewed with a brewer from De Struise of Belgium.

While it only takes a few weeks to make a beer, the collaboration with Sebago has taken years to ferment. In late fall of 2013, Sebago co-founder Kai Adams and Eric Michaud shared a ride home from a Maine Brewers’ Guild meeting in Augusta and hatched the idea for a whiskey. Whiskey is made from the same ingredients as beer (minus the hops), but distilled rather than fermented.

Sebago sold Liquid Riot some leftover Bonfire Rye ale. Liquid Riot ran the beer through its still, then it was aged in American white oak barrels for 16 to 18 months.

The result is an interesting, complex whiskey that clocks in at 45 percent alcohol. The spicy, slightly sweet liquor will be available only at Sebago’s four southern Maine brewpubs. The liquor will be released April 28 and there are just 200 12-ounce bottles, so it’s only expected to be available for a couple of days. More will be released in August and beyond, as Liquid Riot and Sebago both say the collaboration is ongoing.

Adams says both breweries have something to gain.

“(Liquid Riot) has a unique crowd they’re pulling from. Ours is broad-based, their’s is very niche-y and I think we both have something to gain,” Adams said. “It’s great for Liquid Riot because they’re on the shelves of four of the highest-volume restaurants in southern Maine, and get in front of a lot of consumers.”

For Sebago, which sells six-packs of beer in grocery stores across Maine, collaborations are an effort to get in front of more beer fans. As Adams talked about the Bonfire Spirit collaboration, he was preparing to go to The Great Lost Bear, a Portland beer bar with which Sebago brewed a collaboration beer.

Meanwhile, Portland’s Little Tap House was working on its annual collaboration with Saco brewer Barreled Souls, Death Star III, which is a mix of three different styles of beer.

“(It’s about) creativity and community,” Little Tap House co-owner Brianna Jaro said. “Beer has always been a unifier in the traditional pub-sphere – strike up a conversation over a pint! – but with the growth of microbreweries in Portland, there’s an opportunity for a very intimate and inclusive experience for all.”

The spirit of cooperation extends down to a technical level.

When Adams was starting Sebago in 1998, a brewer friend from Casco Bay Brewing Co. came over to put his filters in. The Maine Brewers’ Guild maintains a catalog of excess ingredients and machinery for sale between breweries.

And when Fore River Brewing Co. was starting in late 2015, Banded Horn Brewing Co. invited the co-founders of Fore River to hang out in its brewery to help them learn how to run a commercial system.

Fore River’s T.J. Hansen, a former auto mechanic, still marvels at the cooperation.

“It’s just different for me because if I had a problem with a Volvo or something, and I called the dealership, they weren’t helpful,” Hansen said. “They just say, ‘You’re on your own.’ It’s just a really cool thing to be a part of this brewing scene.”

Eric Michaud, co-owner of Liquid Riot, says brewers are always happy to help because there is a reputation at stake.

“On the brewing side, from a business standpoint, we have a really good thing going,” Michaud said. “Maine beer has a fantastic reputation. We don’t want somebody coming in and making crappy beer and ruining that reputation. We recognize anybody can open a brewery. So if they’re going to open, it’s in all our best interest to make sure they make great beer.”

But will that spirit of collaboration ever turn to competition? Maybe.

“I think there is a line, I just haven’t found it yet,” Adams said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.