How close is close enough?

That’s the question at the heart of a court battle that will determine whether Mainers get to vote this fall on a proposal to legalize the recreational use of marijuana.

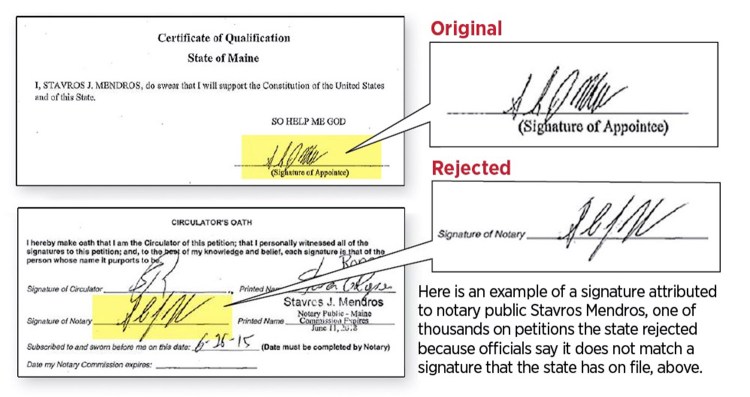

Secretary of State Matt Dunlap has rejected thousands of petitions signed by registered Maine voters who want to put the marijuana question on the Nov. 8 ballot. He says the petitions are invalid because the signatures of several notaries public who signed them do not match the signatures that are on file with the state.

The Campaign to Regulate Marijuana Like Alcohol, which organized the petition drive, has sued Dunlap over the decision, arguing that he did not review all of the disputed signatures and is not qualified to determine if they match.

Most of the disputed petitions were notarized by Stavros Mendros, a former legislator from Lewiston whose company was hired by the marijuana campaign to gather voter signatures. Mendros, who has previously declined to comment on the dispute, said in an interview Friday that he personally notarized all of the petitions that bear his signature.

The Maine Sunday Telegram obtained copies of the 6,279 disputed petitions under the Freedom of Access Act last week. The Telegram reviewed the signatures in question, comparing them with the signatures used as a reference by the state. The newspaper also forwarded a number of the signed petitions and the reference signatures to an independent handwriting expert who frequently testifies as an expert witness in court cases.

The expert observed variations in the signature of Mendros, who notarized more than 5,000 of the petitions, but said they were within the “natural range” of variation and could reflect the sheer number of signatures Mendros had to make.

If that opinion holds weight, it suggests that the state of Maine may have a difficult time convincing a judge that the notary signatures are so irregular or questionable that the petitions must be invalidated.

In Kennebec County, Superior Court Justice Michaela Murphy must rule on the case by April 11. A ruling is expected by the same day in a separate case over the notary signatures on a petition to establish a casino in York County. Many of those petitions were also notarized by Mendros, whose company was hired to gather voter signatures for four different campaigns to put a referendum question on the Nov. 8 ballot.

SIGNATURES LABELED ‘WIDELY VARIABLE’

To get a question on the ballot, Maine law requires petitioners to collect registered voter signatures equal to at least 10 percent of the total number of votes cast for governor in the last gubernatorial election. The required number of signatures to qualify for the ballot is currently 61,123.

Those who circulate petitions must submit the signatures to a notary, and then sign the petition themselves to swear that they witnessed each voter sign the petition. The notary also signs the petition.

Secretary of State Matt Dunlap, whose office oversees initiative campaigns, says the signatures of five notaries public did not match what the state has on file. Kennebec Journal File Photo

Kristen Muszynski, spokeswoman for Dunlap, said it is a “best practice” for the notary to sign the petition immediately after it is signed by the circulator.

The majority of the marijuana petitions that were thrown out were signed by Mendros, whose signature appeared on 5,099 petitions containing roughly 17,000 voter signatures. Had those petitions not been thrown out, the question would have qualified for the November ballot.

Dunlap, whose office oversees initiative campaigns, says Mendros’ signatures don’t match the signatures on file with the state and the petitions are therefore invalid. That view was presented in court by Phyllis Gardiner, an assistant attorney general. She said Mendros’ signatures on the petitions were so irregular that Dunlap could not determine if they had been signed by Mendros, who runs Lewiston-based Olympic Consulting. His company was involved in gathering signatures for four different campaigns.

“The notary signatures on Mr. Mendros’s petitions were so widely variable and unrecognizable as his official notary public signatures that the (secretary of state) could not determine whether he had, in fact, administered the oath to 86 different circulators – an oath which is absolutely critical to ensuring the integrity of the initiative process,” Gardiner wrote in court documents.

While Mendros’ petitions are at the center of the court appeal, Dunlap also ruled invalid because of signature inconsistencies petitions signed by four other notaries: Elliot Chicoine, James Tracey Jr., Jacob Darveau and Wendy Tinto. Mendros, Chicoine and Tracey submitted to Kennebec County Superior Court sworn affidavits saying the petitions contained their original signatures. Eight circulators signed affidavits saying they watched Mendros sign petitions.

An attorney for the marijuana campaign takes a different view of the signature variations.

“Our view is this is a basic test,” said Scott Anderson, an attorney from Verrill Dana. “You made sure someone didn’t sign ‘Mickey Mouse,’ with an ‘X’ or with something that’s completely unintelligible as their signature. For Stavros, when you look at his signature, there’s variability, but there’s an S, there’s a J, there’s an M. They look like his name on file.”

Anderson said Dunlap “did not even review every notary signature invalidated on the grounds that the signature did not ‘match’ the signature on file. Instead, the secretary of state reviewed a portion of the notaries’ signatures and then disallowed all petitions signed by those notaries.”

Mendros, who until last week had not commented on the situation, questioned Dunlap’s decision to throw out his signatures from three campaigns while not taking issue with his signatures from a fourth – on ranked choice voting.

“They threw out every single signature I signed on the marijuana petition, the casino petition and the education petition because they were inconsistent. I don’t know how they all could have been,” Mendros said Friday. “I signed 15,000 documents over the course of 60 days. My signature was not the exact same 15,000 times. I don’t know how you could expect me to do that.”

MENDROS: ‘IT’S MY SIGNATURE’

The Campaign to Regulate Marijuana Like Alcohol turned in 99,229 signatures on Feb. 1, the deadline to submit citizen initiative petitions to the secretary of state. The submission of those signatures came at an especially busy time for the Secretary of State’s Office, which, during a six-week period from Jan. 14 to March 2, had to determine the validity of more than 100,000 petitions containing nearly 450,000 signatures.

Before reviewing the marijuana petitions, the Secretary of State’s Office was validating petitions for other citizen initiatives, including one that would allow a developer to build a casino in York County and another to strengthen background checks on gun sales. Some of the signatures on those petitions raised red flags and prompted election officials to scrutinize more closely the marijuana petitions, said Gardiner, the assistant attorney general, in a court filing.

Election officials found that 32,526 signatures on the casino campaign were invalid because either the signature of the circulator or notary did not match the signature on file.

Dunlap invalidated 47,686 of the 99,229 signatures submitted by the Campaign to Regulate Marijuana Like Alcohol, leaving only 51,543 valid signatures, about 10,000 fewer than needed to qualify for the ballot. Twenty-five percent of the petitions were circulated by 86 people who took an oath before Mendros swearing to the validity of the signatures.

Under a state law amended in 2009, Dunlap has the responsibility of determining if a notary’s signature matches the official one on file with the state. The 2009 change that required notaries to have an official signature on file came after election staff noticed while certifying five citizen initiative petitions that many of the notarizations were done by the same few notaries and that the signature varied widely.

Dunlap has defended his ruling and said he is confident it will withstand the appeal. Dunlap was not available for comment last week because of the pending court action, according to Muszynski.

“The bottom line here is that we don’t look for reasons to disqualify signatures,” Dunlap said in March. “We’re looking to verify that they were made properly.”

Anderson, the attorney for the marijuana campaign, said Dunlap and his staff never contacted the campaign about the signature irregularities before the petitions were ruled invalid, but he believes Mendros and the campaign could have cleared up the issue if the office had talked to them.

“Our concern is we don’t feel the secretary of state has the expertise to do this analysis,” Anderson said.

Former state legislator Stavros Mendros’ Lewiston-based company was hired to gather voter signatures by the Campaign to Regulate Marijuana Like Alcohol. 2012 Associated Press File Photo/Robert F. Bukaty

Mendros said he has worked on nearly 30 campaigns and there have been times when election officials have contacted him with questions about his signature. He said he tried to keep his signatures consistent, but described it as “physically impossible for them all to be the same.”

“Sometimes it got sloppy because I was up at 4 a.m. signing 1,000 documents at the same time,” he said. “People are implying I didn’t sign them all. It’s my signature; any handwriting expert will tell you that.”

EXPERT SAYS SAMPLE SIZE TOO SMALL

The marijuana campaign hired a handwriting expert to examine 100 petitions signed by Mendros. The expert told the court the state didn’t use enough samples to determine if Mendros’ signatures were valid. The sample signatures were those Mendros put on a Certificate of Qualification as a notary in 2011.

“With all due respect to the secretary of state, in my opinion, the two signatures on the Certificate of Qualification do not provide an adequate basis for determining the authenticity of the notary’s signature on the petitions,” wrote Vickie Willard, a forensic document examiner from Ohio. “The results of a comparison using only two specimens from 2011 must be inconclusive (no opinion) on the basis of an inadequate quantity of comparison signatures from which to study the writer’s range of natural variation when executing his signature.”

Jim Streeter, a Connecticut-based forensic/handwriting document examiner who reviewed the petitions for the Telegram, said an initial evaluation indicates that they were signed by the same person. The newspaper forwarded 13 pages to Streeter, including Mendros’ official signature with the secretary of state and 12 pages of disputed petitions where Mendros’ signature appeared at the bottom of the page.

“All of the signatures show patterns that are within the range of the natural variation of that signature,” Streeter said.

Streeter emphasized that it wasn’t his official opinion on the signatures – that would require a thorough evaluation – but was an initial observation.

Streeter said a person’s signature can vary significantly based on how quickly someone is signing a document, and how important the document is.

“If I am signing a mortgage to buy a $300,000 or $400,000 house, I will have a very formal, deliberate signature. I will be taking my time,” Streeter said. “If I’m signing a credit card slip at the gas station, and in a hurry, my signature is going to look quite different.”

Streeter said if someone has to sign many documents within a short period of time – Mendros signed 5,099 for the marijuana legalization petitions – that would also affect the appearance of the signature.

Streeter said to an untrained eye, it might look like different people signing the documents. But he said someone such as himself, who has been trained to evaluate handwriting, can most often tell if it’s the same person signing the documents, even if the signatures look different.

“If I was an elected official charged with determining whether signatures were valid, I would call on a qualified expert,” Streeter said. “Otherwise, what are they basing their decision on?”

Streeter added that he realizes there’s an expense to bringing in expert witnesses, as handwriting experts typically cost about $100 to $200 per hour of work.

Neal Kelley, past president of the National Association of County Recorders, Election Officials and Clerks, said there are time and expense barriers to using forensic handwriting experts to validate petition signatures, because of the volume of signatures that election officials are dealing with.

Kelley said for that reason, most election laws simply require that election workers inspect signatures to determine whether the signatures are valid and match what’s on file.

But Kelley said there’s also a lot of variation among states and counties about how signatures are validated.

“There’s not a nationwide standard for how this is conducted,” said Kelley, the chief election officer in Orange County, California.

Kelley said that in Orange County, election workers receive basic document forensics training so that when they examine petition signatures, they can recognize patterns. But he said they aren’t trained to the level of someone who evaluates signatures on documents for court proceedings.

Staff Writer Joe Lawlor contributed to this report.

Send questions/comments to the editors.