A “landmark” conservation project will protect more than 8,000 acres of prime habitat for deer and wild brook trout in northwestern Maine.

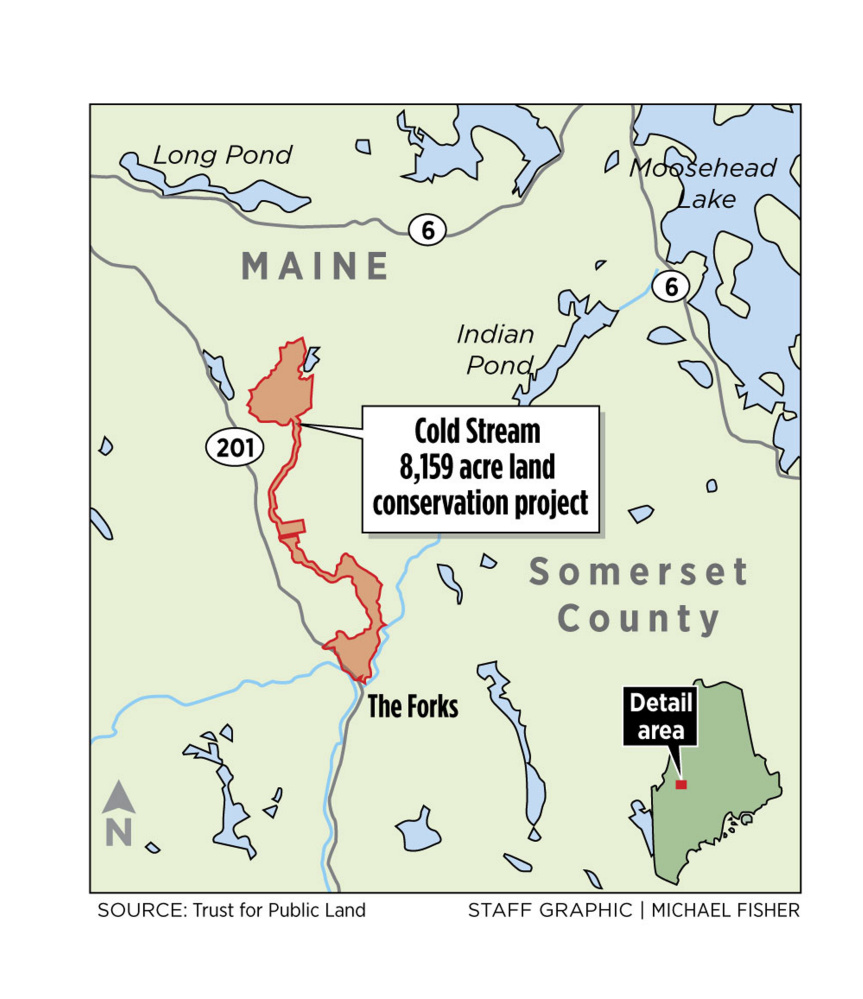

The Cold Stream Forest project, announced on Friday, marks the first time Land For Maine’s Future funds have been used specifically to protect important wildlife habitat. The 8,159-acre parcel is near The Forks in Somerset County, at the convergence of the Kennebec and Dead rivers.

“LMF funds have been invested in bigger projects. This is the first one that really emphasized deer and brook trout habitat,” said Tom Abello, Maine director of external affairs for The Nature Conservancy. “Eighty-one hundred acres is nothing to sneeze at. But the habitat is what is really significant.”

David Trahan, executive director for Sportsman’s Alliance of Maine, called the announcement a “landmark day for conservation land.”

A report by Trout Unlimited in 2006 showed that Maine is the last stronghold in the Northeast for wild brook trout. The state has 97 percent of the intact lake and pond brook trout populations in the eastern United States, which means those waters are not stocked with hatchery fish.

“Maine is the only state in the Northeast where brook trout habitat is not fragmented. Cold Stream is (an example of why),” said Jeff Reardon, Trout Unlimited’s brook trout project leader in Maine.

“Every lake and pond, and literally every inch of stream, is full of brook trout. You can find that in other places in northern and western Maine, but they’re not quite as good as Cold Stream. And you don’t find it in other states.”

The land was purchased from timberland magnate Weyerhaeuser. It protects the wild trout fishery in the Kennebec and Dead rivers, seven undeveloped ponds that make up the headwaters of Cold Stream and five miles of Cold Stream.

The brook trout fishery is considered a “heritage water,” which means it has never been stocked, or was stocked so long ago it has returned to its natural state functioning as it did before European settlers arrived.

It has been used by fishermen and hunters for generations, Reardon said.

The $7.34 million parcel was purchased with $1.5 million from Land For Maine’s Future, $5.5 million from the U.S. Forest Service’s Forest Legacy Program and $340,000 from private funds. The land is being transferred to the Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry to become part of the state’s Public Reserve land system. Conserved land is routinely transferred to the department when Forest Legacy funds are involved.

There have been LMF-funded projects and other conservation projects that are far larger – on the scale of 40,000 to 185,000 acres. But this is the first that focused specifically on conserving deer wintering areas and wild brook trout habitat – because of a directive of the last LMF bond that went to state voters in 2012. That bond directed the state, for the first time, to seek these types of conservation projects to be considered for LMF funding.

The statute says: “The Department of Conservation and the Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife shall take a proactive approach to pursuing land conservation projects that include significant wildlife habitat conservation, including conservation of priority deer wintering areas.”

Land For Maine’s Future was at the center of a legislative conflict in 2015 because Gov. Paul LePage refused to release bonds targeted for the agency. That conflict, however, did not affect this project, said Bill Vail, the former LMF chairman.

“No, in fairness, (the project) would not have been ready. It needed significant Forest Legacy funds. That money wasn’t ready,” Vail said.

On Friday, the conservation community was rejoicing over the news of the Cold Stream Forest transfer.

Joe Kruse, owner of Lake Parlin Lodge in The Forks, said the protection of access is significant to sportsmen because the land is so ecologically rich in wildlife populations.

“I see this project as a great economic boost to the folks in this area because it preserves the traditional recreational uses here and the wildlife resources here. That’s the beauty of this land,” Kruse said.

And fishermen Joe Dembeck said there are sections of this remote parcel that are hard to get to, and that will help preserve its wild character as anglers now flock to these waters.

“It was really nice to see the two driving forces were the native wild brook trout and the very large deer yard on the lower end of the stream,” Dembeck said. “Those were the two main items pushing the preservation here. The recreation was important. But it was not the primary area.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.