ORONO — The magic has gone missing from Alfond Arena, the distinctive chalet-shaped home of a Maine hockey team that once stood among the best in the nation.

The average crowd this winter dipped below 4,000 for the first time, a 29 percent decrease from a decade ago. The athletes in the familiar white-and-navy sweaters gave those few fans little to get excited about, skating to a dismal eight-win season that was the program’s second-worst showing ever.

If this was rock bottom, all indications are that it could be a slow climb back to respectability for a Black Bears team that was once the pride of the state.

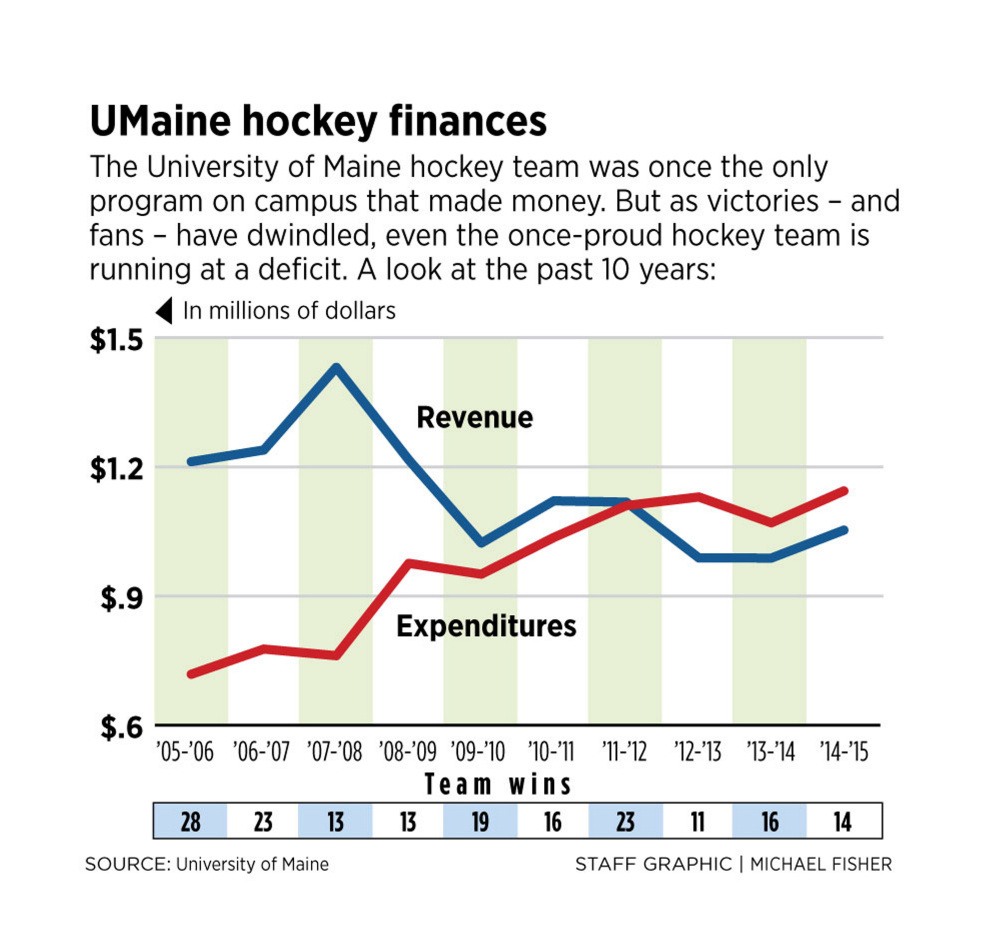

Maine won national championships in 1993 and 1999 and made 11 trips to the NCAA semifinals – the hallowed Frozen Four – in a two-decade span between 1988 and 2007. In the nine years since, the Black Bears have made the NCAA tournament only once (a first-round loss in 2012) and suffered five losing seasons. The program’s revenue is down by 26 percent since 2008.

The college hockey landscape has shifted while Maine’s fortunes have plummeted. There are more teams to contend with, bringing more parity and heated competition on the recruiting trail, which is where champions are ultimately born. And the young players the Black Bears are targeting are unlikely to be impressed by what happened in Orono years before they were born.

“There may be some lingering mystique to the program, but it’s lost on today’s recruits,” said Dave Hendrickson, a Maine native and veteran writer for U.S. College Hockey Online. “The core (group of fans) is really important. If you’ve got a lot of apathy on the campus and in the surrounding community, then you’re really fighting an uphill battle. Can (Maine) give a reason for those who are outside of that core to become energized?”

‘THERE WOULD BE CHALLENGES’

That’s the challenge facing Red Gendron, whose third season as head coach ended last weekend with an 8-24-6 record. The only worse team in Maine hockey history was the 1982-83 version that finished 5-24 (the 1993-94 team was officially 6-29-1, but only because it forfeited 11 wins and three ties for NCAA rules violations).

The Black Bears ranked 56th of 60 Division I teams in scoring, at 2.0 goals per game, and weren’t much better at defending their net, surrendering 3.39 goals per game to rank 50th. None of the teams that Maine beat boasted a winning record.

Maine’s victory totals have declined in each of Gendron’s three seasons, from 16 the year after he took over from Tim Whitehead, to 14 last winter and now eight.

Maine players celebrate their NCAA Division I Hockey Championship win in Anaheim, Calif., in April 1999. The late coach, Shawn Walsh, “got the ball rolling and the ball rolled for a long time,” said Dave Hendrickson, a Maine native and writer for U.S. College Hockey Online. “But once you’ve lost that allure as one of the top three or four teams in Hockey East, than can change fast.”

So Maine Athletic Director Karlton Creech raised some eyebrows in February when he rewarded Gendron with a two-year extension to the original four-year contract he signed, taking him through 2019 at an annual salary of $209,100 that is the highest in the department. It was a sign that Creech believes the next three years will be significantly better than the last three for his hockey program.

Gendron is convinced of that as well, and said he feels no pressure.

“I knew when I chose to take this job that there would be challenges and I was committed to doing things the right way,” said Gendron, who was an assistant coach at Maine under Shawn Walsh during the 1993 championship season. “If it took time or it was painful, I was prepared to deal with that.”

Gendron has taken the long view to rebuilding the program, opting to honor the commitments made by Whitehead with two exceptions (J.T. Henke and Zach Glienke). The final class of Whitehead recruits will be seniors next year. It’s worth noting, however, that the two best players by far of the Gendron era have been forward Devin Shore and defenseman Ben Hutton, both Whitehead recruits who left after their junior seasons and played in the NHL this year. Those departures, not unexpected, left the cupboard particularly bare for the Black Bears this winter.

Gendron conceded that his team’s struggles in Year 3 surprised him. But he pointed to the fact that this year’s Black Bears played 12 games that went into overtime, including both of their losses at Northeastern that eliminated them from the Hockey East postseason. He remains bullish on the nine freshmen who arrived last fall. That group combined for a mere eight goals, but includes what Gendron believes is his goaltender for the future (Rob McGovern) and potential stars in forward Brendan Robbins and defenseman Rob Michel. Gendron is even more enthused about the nine players poised to join his program this fall, including three who were chosen in last year’s NHL draft.

ENDOWMENT EFFORT IS LAUNCHED

No one is more optimistic about the future of the Maine hockey program than Tom Savage. The Bangor native and 1968 graduate of the university was so sure that his favorite team can be revived that he pledged $1 million in December 2014 to make that happen. That money is intended to be matched by donations from other alumni to form a $2 million endowment within five years. So far, $300,000 has been raised, according to Seth Woodcock, Maine’s associate director of athletic development.

UMaine’s Cam Brown reaches for the puck in a game against North Dakota last fall. The team ended its season last weekend with an 8-24-6 record, the second worst in Black Bear history.

Savage, who lives in Florida but makes it back to Orono for about 10 games a season, said he’s realistic about what can be accomplished at his alma mater. The days of routinely reaching Frozen Fours are likely past.

“I would be very surprised to see anybody have the run we had. I think people need to realize that. I talk to people about that ’93 team (which finished an incredible 42-1-2) and I say you’re never going to see anything like that again,” Savage said. “I’d like to see that a lot of years we’re in the top half of Hockey East and you get opportunities to get in the NCAA tournament, to be competitive at a higher level than we are right now.

“Within the next three years, I’d expect us to be back in the tournament, maybe two years. Red’s still recruiting, he’s still getting people. We’ve lost a lot of games this year, but we’ve played a lot of teams tough, too. You can see they just had a little bit more guns than we did.”

Longtime Black Bears fan Matt Taylor isn’t despairing, either. The 31-year-old from South Portland grew up rooting for Maine hockey, remembering the 1999 title team fondly. He even attended the 2006 Frozen Four in Milwaukee, where Maine lost to Wisconsin in the semifinals.

Those Badgers are a perfect example of how difficult it is to sustain excellence in college hockey, Taylor pointed out. A winner of six national championships, Wisconsin limped to a 4-26-5 record last year, its worst in 82 seasons. This winter hasn’t been much better, with a 7-17-8 record.

“It’s just like a pro sports team, you’re not going to have many that are up there every year,” said Taylor, who attended the three games Maine played in Portland this winter but none in Orono. “You get teams like Providence winning titles, Yale winning titles, teams that you wouldn’t think would be a national power.

“Parity is definitely there and I think it’s good for the game as a whole. Would I like to see Maine up there competing for national titles? Yes. Is it feasible? No.

“I want a team that’s competitive, a team that plays hard. I want a team that’s proud every day to put on a Maine sweater.”

‘FINDING THE RIGHT KIDS’

Alfie Michaud knows what it’s like to wear that sweater. The 39-year-old was spotted, like most of Maine’s stars of the past, by legendary recruiter Grant Standbrook when he was tending goal in his hometown of Selkirk, Manitoba. In 1999, Michaud backstopped the Black Bears to their most recent national championship, racking up a 28-6-3 record with a 2.32 goals-against average.

Michaud still lives in Vienna, west of Augusta, and trains young goaltenders, here and in his native country. He’s also an unofficial scout for his alma mater, happy to pass on information about any talented youngsters he sees. He’s eager to see his Black Bears get off the mat, and confident that the current coaching staff – which includes his former roommate Ben Guite as an assistant coach and recruiter – can engineer a turnaround.

“Maine has a winning tradition and they’ve gotten a little beaten and battered here the last few years,” Michaud said. “It’s a matter of finding the right kids. It kind of seemed like we were all small-town, rural kids who didn’t mind going to a rural area. We just wanted to play hockey and win hockey games, and we bled blue.

“But it’s tough if you’re not winning. You’ve got your die-hards, but it’s hard to draw those other ones. You’re not seeing as many Maine Black Bears jerseys at the central areas (of Maine), but they’re popping up more and more in the rinks.”

Michaud was one of a long line of stellar goaltenders that used to define Maine hockey. Jimmy Howard, Ben Bishop and Scott Darling are among the current Black Bear alumni in the NHL. Garth Snow was the forerunner, starring on the 1993 team. Now the general manager of the New York Islanders, Snow is one of a number of former players who have put up money for the school’s new endowment.

That $2 million, once it is reached, will be vital to ensuring the long-term success of the team, Woodcock said. Revenue is down 26 percent for the Maine hockey program – the only sport at the university that has a chance to make money – from $1.43 million in 2008, the year after its last Frozen Four appearance, to $1.05 million last year.

Endowments are becoming popular ways to provide reliable sources of funding. For example, Ferris State, in Michigan, announced this month that it has completed a campaign to establish a $1.5 million endowment. That principal remains untouched, but whatever investments it earns go to the hockey team to boost recruiting, or pay for travel and equipment.

Red Gendron has coached the Black Bears hockey team since 2013; a contract extension keeps him in the job through 2019.

“You want to sell tickets and generate revenue that way,” Woodcock said. “This protects you in the long haul and puts you in a strong financial situation.”

Savage said he’d been considering for years donating money to establish an endowment at Maine. He was a backer of Whitehead, the former assistant who took over after Walsh died in September 2001. Whitehead, with Standbrook still helping supply talent, took Maine to the national title game that year and again in 2004. But he reached only one NCAA tournament in his final six years as coach and was dumped in favor of Gendron. Savage is firmly in Gendron’s camp as well. But he came to believe just attending games wasn’t enough.

“I realized we need to help our program from the outside, too. I watched it from Day One and watched it progress and watched the people come and the enjoyment. I said, ‘We need to keep this,’ ” Savage said.

“Hopefully, more people support it. I’m there. I’m not leaving. I’ve committed my money and my heart.”

TALENT WILL DETERMINE FATE

Gendron has committed 5 percent of his salary to Savage’s effort. His goal is to have $500,000 raised by the end of next season. Of course, he hopes to have more on-ice victories to tout by then as well.

“It was disappointing to watch Maine lose that many games, but there were a lot of games that were awfully entertaining, and you saw kids blocking shots, finishing checks and winning battles and taking pucks to the net,” Gendron said. “And I will also say, hey, it wasn’t good enough. I’m not telling anybody they should come and watch us just because we battle. But it’s certainly a good reason to not give up on these kids.”

Maine wasn’t always competitive this winter, however. The Black Bears, lacking star power without Shore and Hutton, lost seven games by four goals or more. There were nights when there was a wide and evident gap in talent between Maine and its opponent.

Ultimately, it will be talent that determines Gendron’s fate. Gone are the days when Standbrook could venture to British Columbia and pluck a once-in-a-generation player like Paul Kariya for the Black Bears. Now, thanks to the Internet and increasing recruiting budgets throughout college hockey, there are no untapped areas of the world. Maine recently got two verbal commitments from German players, such is the international pursuit of would-be hockey stars.

Will they be good enough to win, and to help restore the luster to Alfond Arena? The latter can’t happen without the former.

“In Maine’s glory years they were getting a whole lot more of the elite athletes. The best players always like to go where they win,” Hendrickson said. “Shawn Walsh got the ball rolling and the ball rolled for a long time. But once you’ve lost that allure as one of the top three or four teams in Hockey East, that can change fast.

“Once the bloom is off the rose, it can be difficult to restart that perception that a given program is the place to play. The expectation would have to be more modest than that. At this point, it’s hard to see the next Paul Kariya going to Maine, and that’s no offense to anybody.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.