Only a year ago, Republicans were congratulating themselves on having the strongest field of presidential candidates in a generation – diverse, highly credentialed conservatives who might be the salvation of a party that lost the popular vote in five of the last six elections.

But now, the question is how close the Grand Old Party will come to annihilating itself and what it stands for.

Donald Trump – dismissed by party elders for months as an entertaining fringe figure who would self-destruct – has staged a hostile takeover and rebranded the party in his own image. What is being left by the wayside is any sense of a Republican vision for the country, or a set of shared principles that could carry it forward.

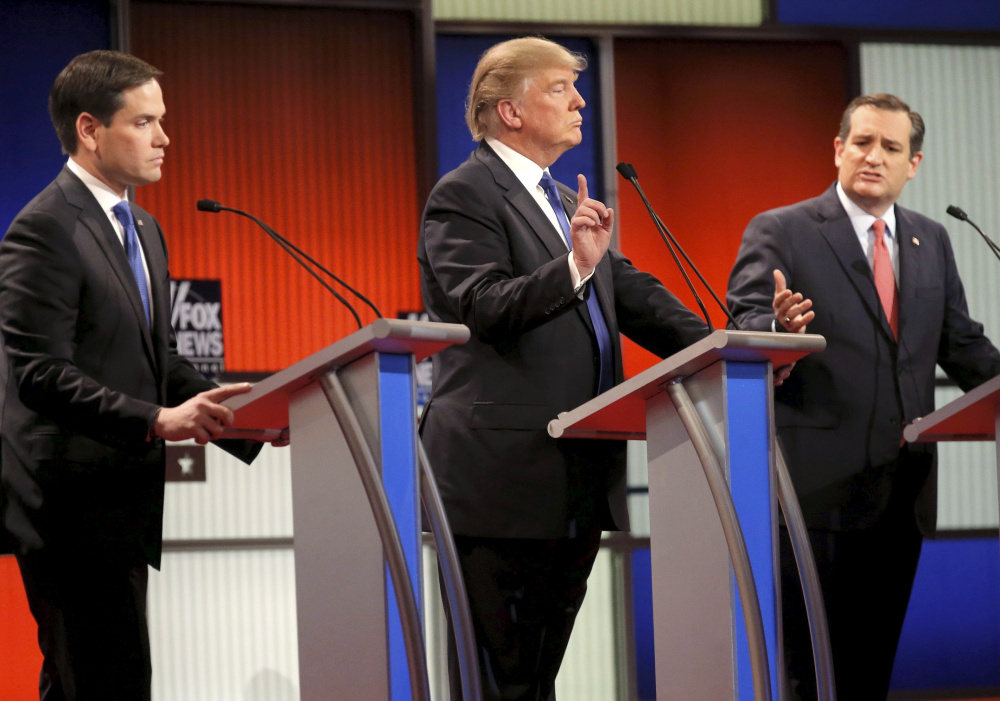

A substance-free shoutfest billed as a presidential debate on Thursday night marked a new low in a campaign that has had more than its share of them.

The increasingly prohibitive front-runner and his three remaining opponents spent nearly the entire two hours hurling insults back and forth, with Trump at one point making a reference to the size of his genitalia.

“My party is committing suicide on national television,” tweeted Jamie Johnson, an Iowa political operative who had been an adviser to former Texas governor Rick Perry, one of the 11 Republicans whose presidential campaigns have already been incinerated by the Trump phenomenon. The latest, retired neurosurgeon Ben Carson, formally dropped out Friday.

‘VERY DISTRESSING FOR MOST’

“Republicans in general tend to be a group of people who like to view themselves as serious, having decorum, being orderly, being thoughtful,” said Roger Porter, who served as a senior policy official in the White Houses of Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush, and who is now a professor at Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government.

But, he said, the debate “was the culmination of a long process of the people running for president this year finding themselves drug into a maelstrom in which they look anything but serious and calm and thoughtful and responsible. That’s very distressing for most Republicans. How did we get to this situation?”

More urgent, say many Republicans, is the question of how they get out of it.

Part of the decision is how to handle Trump himself.

Republican leaders are divided. Some are focusing their efforts on stopping the billionaire celebrity, even if it means overturning the will of Republican voters at the July convention in Cleveland. Others are arguing that they should be coalescing behind him, so that they will have their best chance this fall of beating Hillary Clinton.

Beyond that, some worry that even as Trump is bringing record numbers to the polls in the primaries, he is changing the very identity of the party. He is a new kind of Republican, one who flaunts his apostasies on conservative principles, who slings vulgar and divisive language, and who has an ostentatious disregard for the system.

INSIDERS VS. OUTSIDERS

All of which capture a current in the electorate. “The main pendulum in American politics is no longer swinging from left to right. It’s swinging between insiders and outsiders,” said Sen. David Perdue, R-Georgia. “It’s those in the political class against those who are not – that’s the divide in the country, in the party.”

Arthur Brooks, an independent who heads the conservative American Enterprise Institute think tank, said “this is completely predictable, given where we are in the recovery from our financial crisis.”

“Financial crises take 15 to 20 years to clear, as a historical matter, and after two or three years, wealthy people have recovered, but working people haven’t,” he said. “So the result is they turn to populist solutions, and that’s exactly what we’re seeing.”

The GOP has always had internal tensions, but they have generally been over ideology – pitting its internationalists against its more libertarian noninterventionists on foreign policy, or its supply-siders versus its deficit hawks on fiscal issues.

“What is happening now is bigger and less remediable in part because the battles in the past were over conservatism, an actual political philosophy,” Wall Street Journal columnist Peggy Noonan, a former Reagan speechwriter, wrote in the wake of Trump’s string of victories on Super Tuesday.

“We are witnessing history. Something important is ending,” she added.

During the debate, Sen. Marco Rubio, R-Florida, insisted, “We are not going to turn over the conservative movement, or the party of Lincoln or Reagan, for example, to someone whose positions are not conservative. To someone who last week defended Planned Parenthood for 30 seconds a debate stage. To someone, for example, that has no ideas on foreign policy – someone who thinks the nuclear triad is a rock band from the 1980s.”

Nonetheless, Rubio said he would support Trump if he is the party’s nominee. So did Sen. Ted Cruz of Texas and Ohio Gov. John Kasich.

DIVIDED ON TRUMP’S IMPACT

That is in part because the party put itself in handcuffs on that question last September, when its leaders were terrified that Trump would bolt and run as an independent. He signed an oath to support whoever wins the nomination.

Now, it is arguable that Republicans would be better off if Trump had launched a third-party bid. Presumably, he would have been training most of his fire on Clinton, rather than the Republicans he mocks as “Little Marco” and “Lyin’ Ted.”

Still, Republicans are closely divided on the impact that Trump is having on their party image. In a December Marist poll for MSNBC and Telemundo, 43 percent said he is helping their brand, while 40 percent said he is hurting it.

However, the numbers showed a negative trend from the same poll three months earlier, in which 48 percent said Trump was an asset to the party’s image, and 35 percent said he was damaging it.

Where Noonan and others see the Trump phenomenon as a sea change for the Republican Party, Porter predicted it will be transitory. He noted that the party had gone through a somewhat parallel identity crisis in 1940, when it nominated businessman Wendell Willkie, who only a year before had been a registered Democrat.

Four years later, it turned back to a conventional Republican, New York Gov. Thomas Dewey.

Send questions/comments to the editors.