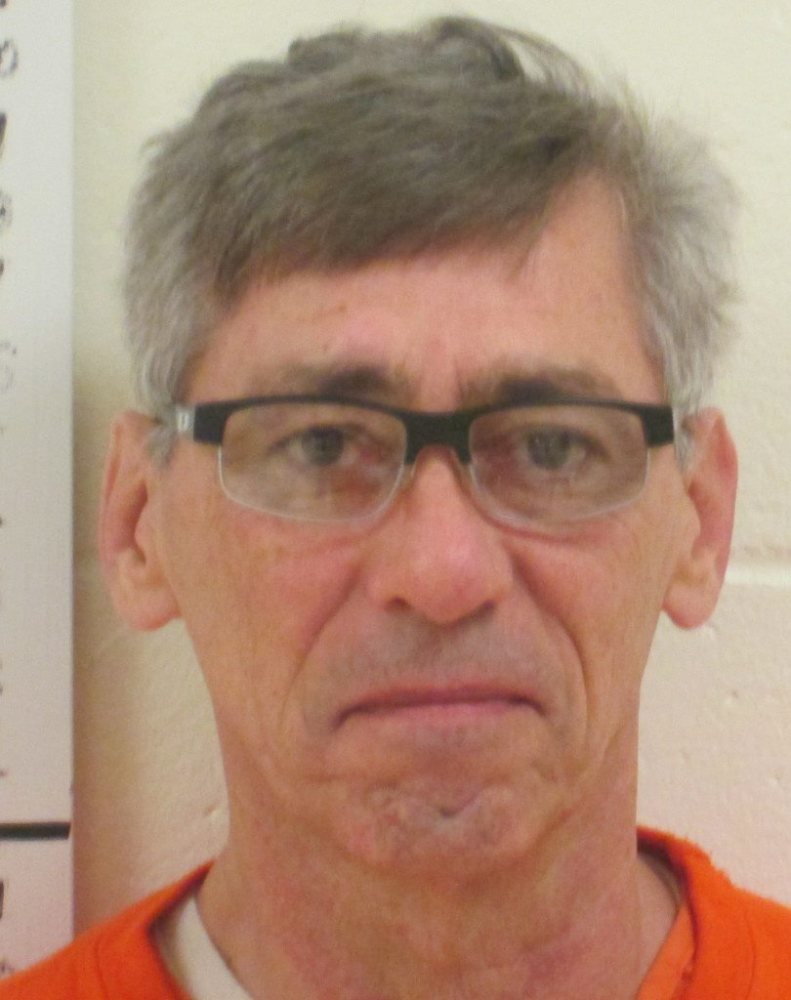

Gregory Owens, a retired Army sergeant major on trial in federal court, had a testy exchange with the judge before deciding Thursday to testify in his own defense against charges he tried to kill his wife during a masked home invasion in Saco in 2014.

Owens protested the judge’s refusal to give him another day or at least more time with his attorney to prepare for questioning, after a Saco police officer testified about waiting many minutes for backup before entering the home where Rachel Owens lay bleeding from multiple gunshots.

“I’m just a tad bit upset,” Owens said, raising his voice and referring to the Saco police as “Keystone Kops.” “I’ve had 15 to 20 minutes at a time with my attorney. All I’m asking for is two hours.”

“I understand that. I’ve denied your request,” Judge Nancy Torresen replied, curtly.

That terse exchange during the eighth day of Owens’ trial in U.S. District Court in Portland took place during a recess, so the jury did not hear Owens’ exchange with the judge or see his temper momentarily flare.

The jurors instead saw Owens showing different emotions: His voice became tremulous, first while he described falling in love with his wife in 1978 while serving in the Army early in his career, and later while describing the death of his Army sniper partner in 1979.

“You think you can handle memories. Sometimes you can’t,” Owens with a deep sigh, taking a moment to compose himself.

Owens, 59, has denied accusations that he drove from his home in Londonderry, New Hampshire, to the home of Steve and Carol Chabot on Dec. 18, 2014, to shoot his wife, who was visiting there.

The masked gunman broke into the Chabots’ house at 25 Hillview Ave. in Saco by smashing the windows of two doors. The gunman shot Rachel Owens three time while she was in bed in a guest room. The gunman then shot Steve Owens three times after they came face to face in the doorway of another bedroom. They both survived. Carol Chabot escaped injury by hiding in a locked third room.

Owens decided to testify a day after a genetic scientist testified that his DNA was found inside a broken window of an outside door to the house that had been smashed by the burglar. The DNA analyst, Jennifer Sabean of the Maine State Police Crime Lab in Augusta, said there was only a 1 in 123 quadrillion possibility the DNA belonged to anyone other than Owens.

Owens walked to the witness stand after the jury returned to the room, and sat facing his wife, who sat in the spectator section of the courtroom for much of his testimony. Rachel Owens sat among relatives and friends with her hands folded in her lap, showing little reaction.

Owens, dressed in a dark suit, had a black mustache and his gray hair was cut in a flattop style. He testified for 90 minutes on Thursday under questioning from his attorney, Sarah Churchill. Owens is scheduled to resume answering questions from Churchill on Friday, followed by cross-examination by Assistant U.S. Attorney Darcie McElwee or Assistant U.S. Attorney James Chapman, who are prosecuting the case together.

Owens’ decision to testify means closing arguments in the trial will likely be Tuesday. The courthouse is closed on Monday for the federal holiday.

Owens began by telling jurors his life story, from his birth in Kentucky followed by his childhood in Kansas, Missouri and Michigan as the son of a store clerk and construction engineer.

Owens said he enlisted in the Army after graduating from high school, beginning a 24-year military career.

It was during sniper training at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, that Owens said he met his future wife, a Saco native who was visiting a friend who was dating a soldier.

“I made the emotional decision,” Owens began, then looked at his wife in the audience, sniffled, cast his head swiftly to the side and wiped his eyes.

“I made the decision that I wanted to be with her,” Owens continued, his voice quavering. “I basically at that point had fallen in love with her.”

After a brief courtship, the couple married in Saco in October 1978, he said.

During testimony, Owens initially forgot the name of the church where he and Rachel Owens were married, before saying he thought it was the former Sacred Heart Catholic Church.

“She’s sitting back there, and she’ll shoot me for forgetting,” he said.

At that remark, many in the audience turned and looked at one another. Rachel Owens, who still has a bullet lodged in her skull from being shot, did not visibly react.

Owens went on to recount his military career, living abroad with his wife and son, Wayne, in such places as Panama, England and Germany before settling in New Hampshire. He told of an infidelity early in his marriage that led to a daughter by another woman, and troubles in his marriage after his retirement from the Army in 1998.

Owens has yet to answer questions about his yearslong affair with another woman in Wisconsin, or trouble with the other woman leading up to the day of the shooting and discrepancies in his alibi both before and after the shooting.

Investigators say Owens shot his wife as his double life of lies began to crumble. His mistress, Betsy Wandtke, testified Monday that she had discovered Owens had not left his wife years before as he had told her. She also came to doubt his claims about being a military operative who went on frequent covert missions overseas, stories he told her to explain his frequent absences.

Owens has pleaded not guilty to two federal counts: interstate domestic violence, punishable by up to 20 years in prison, and using a firearm during and in relation to a crime of violence, punishable by up to life in prison. After the federal trial, he will face state criminal charges, including aggravated attempted murder.

Send questions/comments to the editors.