CHEBEAGUE ISLAND — With a population under 400, it isn’t easy to fill every seat on every board and committee needed to run a town, even with some volunteers serving on more than one.

No one has applied for the animal control officer job that became vacant in December. And since two members stepped down last month, the Board of Selectmen can’t meet when the chairman’s job takes him away from the island.

These challenges are new to Chebeague Island, which has been making its way as an independent town since breaking away from Cumberland in 2007 after 186 years as part of the Portland suburb.

“Growing pains” is how they’re described by Dave Stevens, an islander who traveled to Augusta to advocate for secession at the time.

However, a more troubling problem arose in December. It was discovered that money had been missing from the town coffers since the spring, although it’s not clear how much or why. The Cumberland County Sheriff’s Office is investigating but will only say that it will be awhile, if ever, before it can draw any conclusions.

Meanwhile, a report has called into question whether the town can sustain itself in the long run without population growth, a suggestion that islanders who cherish the tight-knit community are choosing to dismiss.

* * *

Marjorie Stratton, the town administrator since March and fourth person to hold the position in the eight years it’s existed, won’t say how much money is missing or how the shortfall was discovered.

She didn’t have much of an update when Selectman David Hill asked her for one at a meeting Wednesday.

“Just keep us apprised,” Hill said. “There’s a lot of curiosity.”

But islanders insist they’re not concerned.

“I’m sure they’ll get to the bottom of it, and we’ll put it past us,” said Stevens, as he stood in line for soup at the Island Hall Community Center. The center serves a lunch on Wednesdays during the winter, when Doughty’s Island Market, the only year-round store, is closed.

At the Chebeague Island Boat Yard, in an office above the post office and seasonal gift shop called The Niblic, owner Paul Belesca said he’s satisfied that the sheriff’s office is looking into it.

“Things happen,” he said.

Between serving macaroni and cheese at lunch and entertaining students by giving them spiky hairdos, Laura Summa, the island school’s food service director, said she doesn’t think the missing money is a symptom of the town’s youth, but something that could happen anywhere.

“I think it’s one small, weird, quirky thing,” she said.

* * *

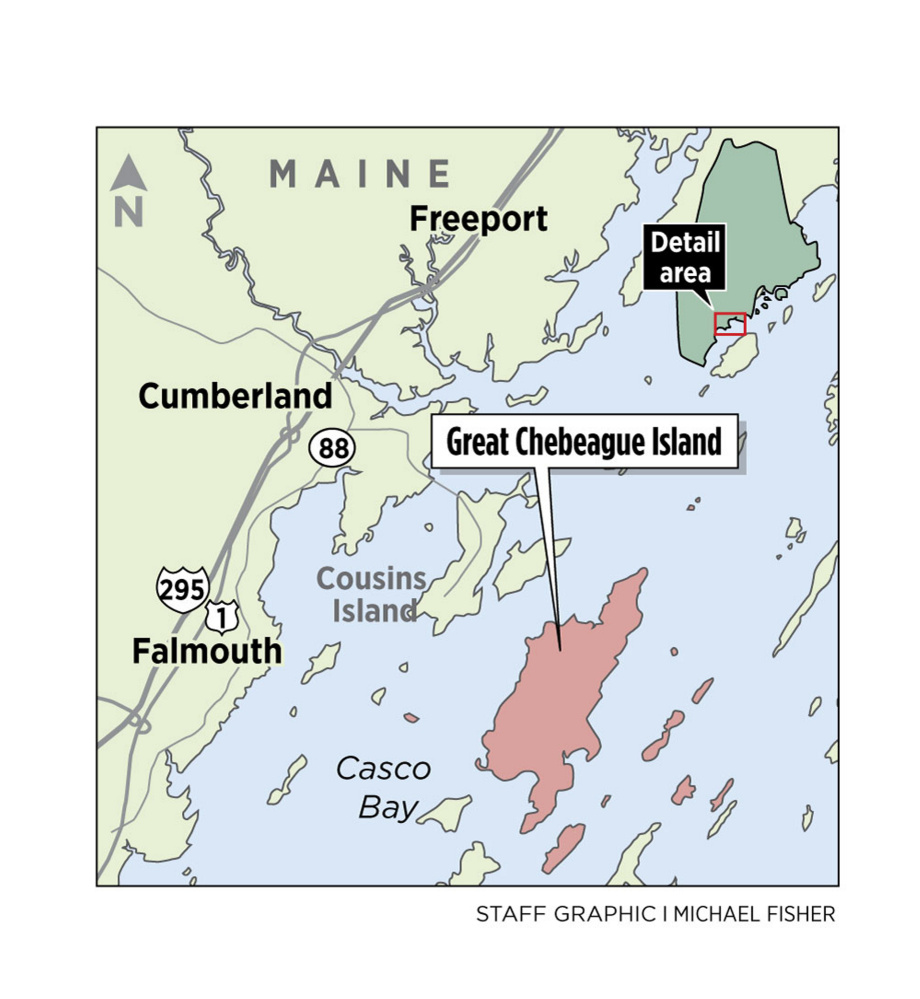

Nearly 5 miles long and a mile-and-a-half wide, depending on whom you ask, Great Chebeague Island is the largest land mass in Casco Bay. It’s actually one of 17 islands that comprise the town, but the only one with a year-round community.

Chebeague Island is the newest town in Maine. And, residents say, it’s the only place they’d ever want to live. The first people to inhabit the island were Native Americans who came seasonally to fish. They were the original summer residents, a group that now swells the population to around 1,500 in the warmer months.

For many summer people, it’s a life goal to live on the island full time and a lot of them eventually do.

Some of them say they prefer the winter, when it’s quiet. Canvas bags filled with groceries don’t have to compete for space on the ferry coming back. Cars can drive the entire island without passing another vehicle, though if they do, they’re guaranteed to get a wave. And the bare trees that line the roads, along with evergreens, give way to glimpses of the water and other islands across the bay.

The year-round head count has hovered around 350 for a while, according to the U.S. Census, though Marjorie Munroe tallied around 400 people this year.

Every year, in the first week of January, she goes through the houses and adds up all the residents, but not by making phone calls or knocking on doors.

“It’s all in my head,” said Munroe, 78, who grew up on the island.

The need to increase the year-round population is emphasized in a draft of the town’s second comprehensive plan, which insists that more people are necessary to fill boards and jobs and bolster the tax base. But not everyone agrees.

To some, the size of the island – about the same as it’s been for nearly a century – is essential to its character. Whether to grow is one of the perpetual debates among residents, along with which roads to pave. Now that the island is its own town, whatever happens is in the hands of the people who live there.

“Before, we could blame Cumberland,” said Stevens.

But now, he said, “we have no one to blame but ourselves.”

* * *

The sentiment was always that the island never got back, in services or infrastructure, a fraction of what it deserved based on the amount of taxes it paid to Cumberland.

So whatever its residents needed, they made happen themselves – the library, the rec center, Internet access.

“We built our own institutions,” said Summa, who answers the school’s phone and helps in the classroom when she’s not in the kitchen.

The gym teacher is also the bus driver and has a clam shack that’s open in the summer. Beverly Johnson, the School Committee chairwoman, teaches technology in her spare time and runs a website that she updates daily with community news.

“Everybody’s on a nonprofit board just about,” she said.

By taking on multiple roles, residents keep the island running. That’s how they knew they could make it on their own.

Talk of secession started when officials from the mainland targeted the island’s school as a way to cut costs.

Their plan was to have fourth- and fifth-graders from the island start going to school on the mainland, meaning kids as young as 9 years old would have had to board the ferry at 6:40 a.m., when it’s pitch black in the winter.

Not only were parents worried about the hours it could take to pick up their kids and bring them home if they got hurt or sick, residents saw it as a sign of things to come.

“It was viewed as a first step toward closing the school,” said Tom Adams, who moved to the island from Portland with his partner, Linda Ewing, around the time that discussion began.

“If you don’t have a school, you don’t have families, and if you don’t have families, you just have another resort,” he said.

That argument won over the state Legislature and both houses voted in near unanimity to allow Chebeague Island to secede.

Since then, the town has paid off the $1.8 million it owed to School Administrative District 51 for taking over the island school and, as it did, managed to lower taxes at the same time.

When the Maine Department of Education handed out report cards in 2014, the school received an “A.” Its enrollment – 22 students in its first year as its own district – has grown to 32 students this year. Families have moved to the island because of the quality of education.

Chris Loder, the chairman of the Board of Selectmen, his wife and their kids are one of them. “The people who said it couldn’t be done were proven really wrong,” he said about seceding.

* * *

But becoming independent hasn’t been without difficulty.

As the town works to identify itself and shape its future, friction among neighbors has grown, islanders say.

Not that it’s anything they can’t handle. After all, they’re people who choose to spend their winters on an island off the coast of Maine.

“We’re able to argue with each other and still live next door,” said Lola Armstrong, who runs the food pantry.

It’s just like any family, they say. And along the same lines, if someone comes upon hard times, whether they’ve lived on the island two months or have a family that goes back two centuries, nothing else matters.

That support system was put to the test in the past year, when residents buried nine of their neighbors – more than they have in recent memory.

There was Kenneth Hamilton, a seventh-generation islander, and Edmund Doughty, whose parents opened the island market, which he ran with his wife.

When a high school student took his own life in September, Pastor Melissa Yosua-Davis, who had only been appointed to the island church in June, was out day and night consoling residents.

And they, in turn, took care of her.

“They dropped casseroles off at our house because they knew how busy Melissa was,” said her husband, Ben.

And just as help comes quickly when someone’s in need, word also spreads when something goes awry. But don’t expect it to go far beyond the island.

Although the missing money may make for talk among themselves, the questions tend to stay within the island family. The public position is that things have never been better on the island.

“The town of Chebeague is a success,” said Belesca, from the boat yard. “I don’t have any concerns.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.