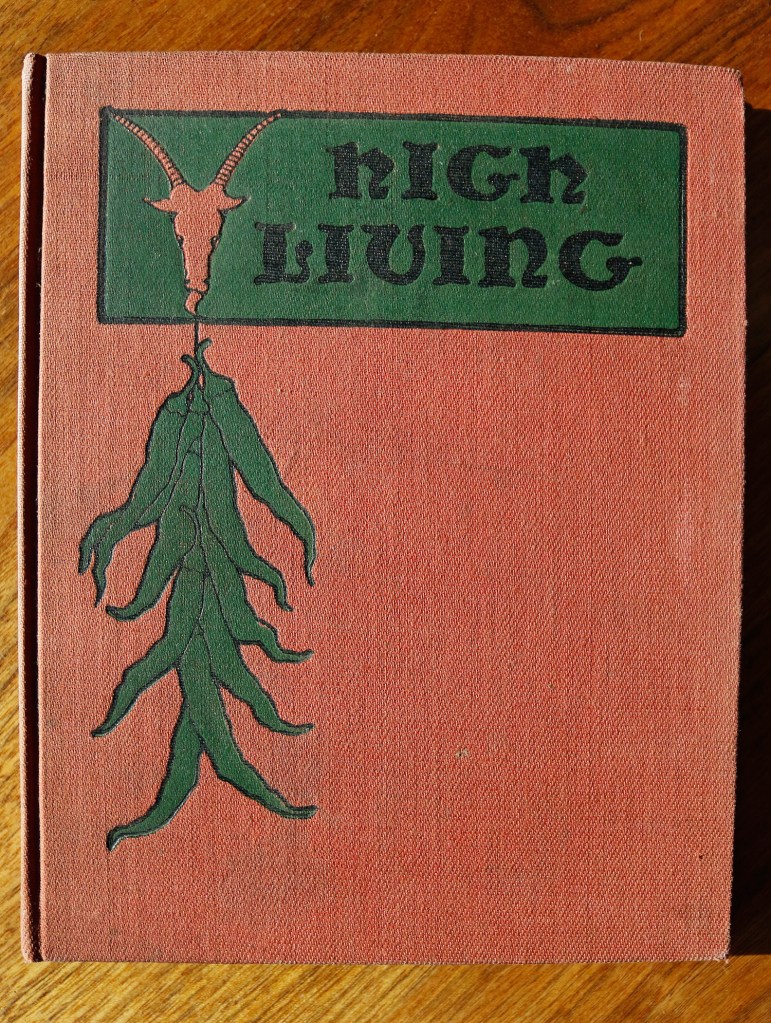

It’s often the odd recipes that initially draw us into vintage cookbooks – the dishes that make us go “eew” and imagine what it would have been like to live 250 years ago and eat brain cakes, cow heel soup, fricasseed pig’s ears or a calf’s head pie seasoned with cocks combs, oysters and mushrooms.

Hungry yet?

But diving into old cookbooks is so much more than pondering how our 18th-century counterparts ate an egg pie made with the shredded yolks of 20 hardboiled eggs, marrow and beef suet mixed in for flavor. Spend some time with the 1772 Boston edition of “The Frugal Housewife” by Susannah Carter, originally published in London in 1524, and you’ll touch history: Paul Revere created two sets of engravings for the book depicting animals trussed and ready for roasting over an open fire.

You’ll find directions for making goose with green sauce, and gravy “to make mutton eat like venison.” You’ll learn how to spitchcock an eel. (“Spitchcock,” a word possibly derived from split-and-cook, refers to splitting an eel along the back and then grilling or frying it. The term dates to the late 15th or early 16th century.)

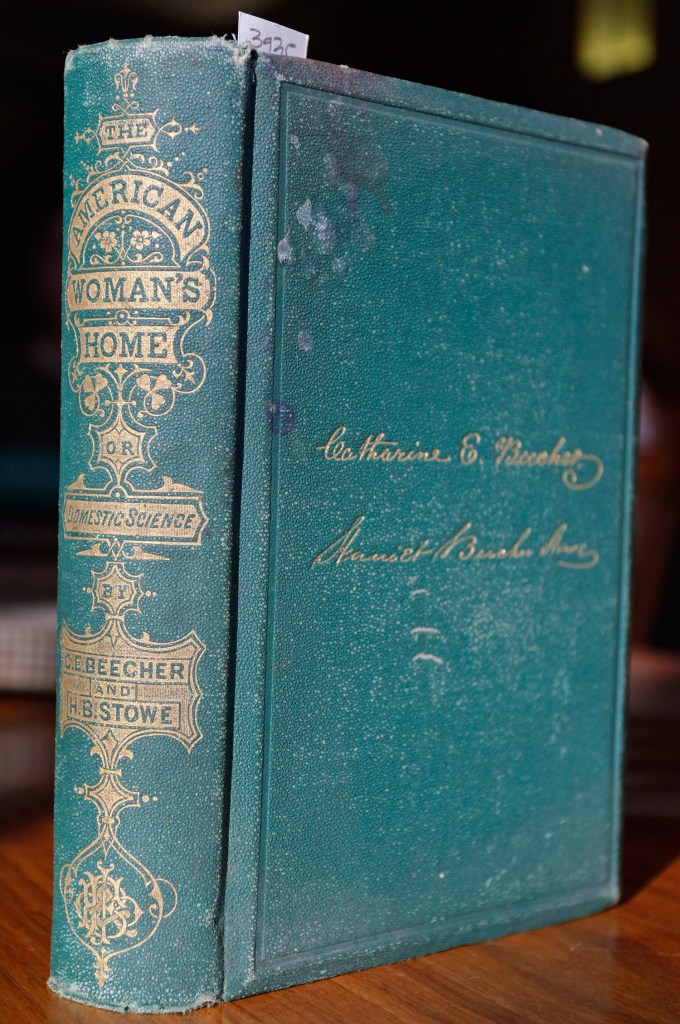

“The Frugal Housewife” is one of more than 700 American cookbooks – and the oldest – in The Esta Kramer Collection of American Cookery, which was donated to Bowdoin College last fall. The collection will be featured in an exhibit that opens next week at the college’s Hawthorne-Longfellow Library, and it is already being used by professional and amateur culinarians to explore the history and evolution of American food.

“We have had food writers coming in and looking at historic recipes and then creating dinners out of those historic recipes,” said Marieke Van Der Steenhoven, outreach fellow for the George J. Mitchell Department of Special Collections & Archives, who is overseeing the exhibition.

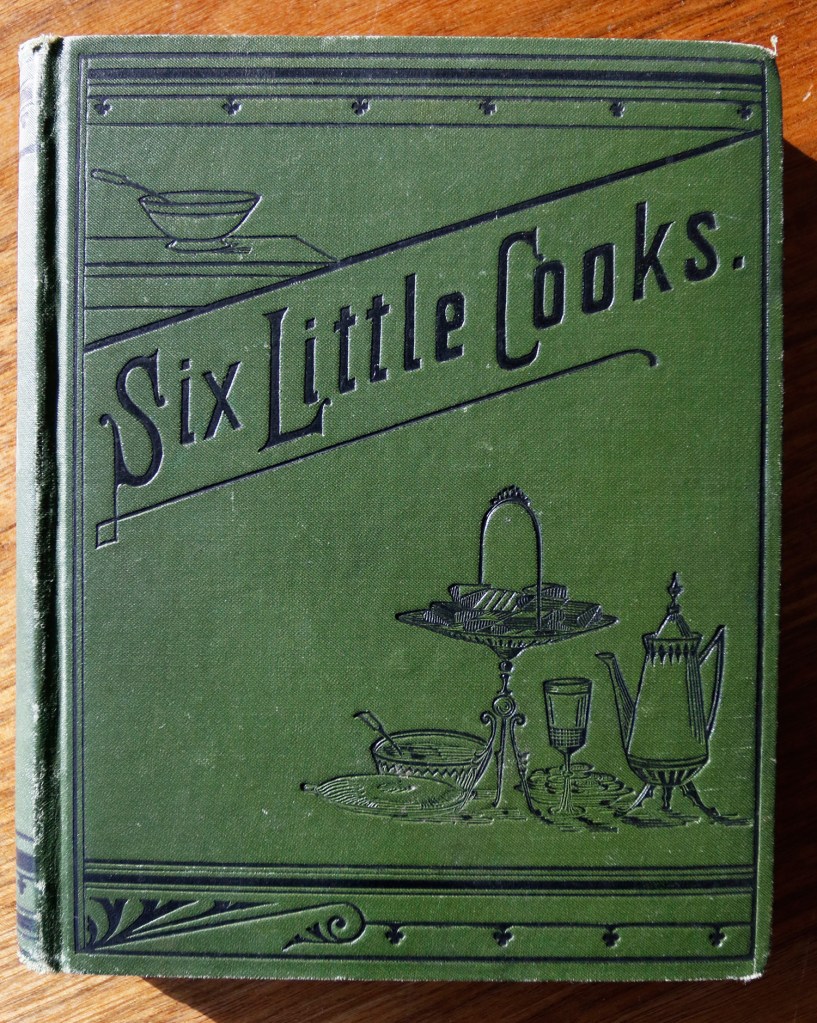

Last semester, a Bowdoin history class, while studying the concept of community, requested some of the community cookbooks – those put together by churches or charities to benefit particular causes, such as “Housekeeping in the Blue Grass,” edited by the ladies of the Presbyterian Church in Paris, Kentucky.

“We have an incredible array from all over the country, including Maine’s first known cookbook, which was published in 1877,” Van Der Steenhoven said. “We presented that to the class, and we talked about the different kinds of community you can find in a cookbook beyond just the recipes. You can look at the local advertisements (old community cookbooks often contain advertisements), and that will tell you what the cookbook was supporting, what it was trying to raise funds for, and a lot of times there’s a lot of incredible information available in the preface.”

A class on public health and the history of medicine examined how these cookbooks handled alcohol – was it medicinal, something to be avoided, or a pleasure to be enjoyed?

The cookbooks are stored in a locked facility, in a climate-controlled environment. As with most archival collections, visitors must leave coats and bags outside the reading room, and a library staffer will fetch the books you ask for. Taking notes is OK as long as the visitor does so in pencil.

OYSTER ‘GOMBO’ WITH CHICKEN, HAM

I spent several hours with about 20 of the books in the collection. As a writer, I loved stumbling across unusual spellings such as “colliflower,” “scate,” “artichoaks” and “poulenta.” In “La Cuisine Creole,” published in 1885, I found lots of “gombo” recipes, including Oyster Gombo with filee. Ingredients: “a grown chicken, 50 oysters and a half-pound of ham to flavor the Gombo.”

I reacquainted myself with long-ago measurements like “a piece of butter the size of a walnut” and a gill (a quarter pint). I learned that in the 18th and 19th centuries, a chocolate cake often meant that the recipe was for a cake to eat while drinking chocolate, not a cake with chocolate in it. I puzzled over the term “Plebian Gingerbread.” Is that what they fed common folk before dragging them to the stocks in the town square?

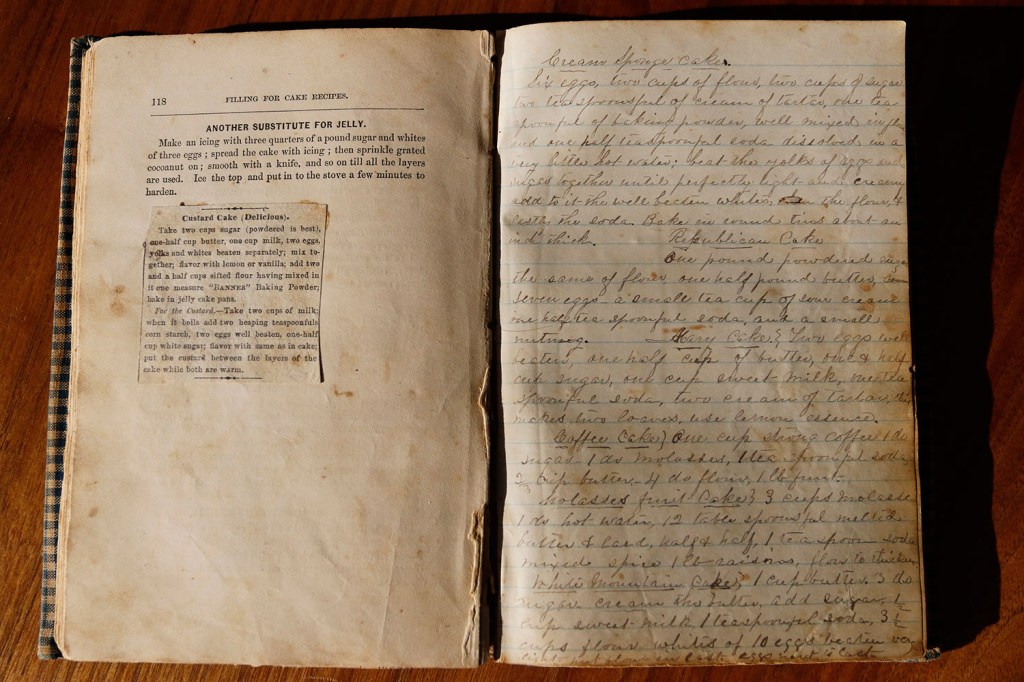

The heart of the collection ranges from Colonial times through the 1800s. Some of the cookbooks contain blank pages where the owners have handwritten their favorite recipes, and more than one owner tucked away a favorite recipe from the local newspaper.

Most recipes are in the narrative style, but the collection does contain the first known cookbook to print a list of ingredients above the directions for a recipe, which is standard today. Its author, Eliza Leslie, published “Seventy-Five Receipts for Pastry, Cakes, and Sweetmeats” in 1828 and went on to write nine other cookbooks, Van Der Steenhoven said, “and did not use that style again.”

I found some recipes I wanted to cook, especially in Mary Randolph’s “The Virginia Housewife,” considered the first regional and the first southern cookbook. Randolph introduced the rest of America to the delights of okra and catfish – even though she does so through the vehicle of catfish soup. Her apricots in brandy and sweet potato pudding sound delightful. And I loved the romantic description of her mint cordial, which requires one to “pick the mint early in the morning, while the dew is on it, and be careful not to bruise it.”

But Randolph also published what is possibly the most revolting recipe ever, for oyster cream, a savory ice cream. Strain the oysters from that leftover oyster soup and freeze. Try not to gag.

I found some great market tips from Hannah Glasse, a hugely popular British cookbook author in the 1800s. In “The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy,” she advises checking the middle of the butter to be sure it’s fresh, and “you cannot be deceived.” If visiting the cheese monger at the market, Glasse writes, “beware of little worms or mites.”

“If it be overfull of holes, moist, or spungy, it is subject to maggots.”

To ensure fresh eggs, she says, hold “the great end” to the tongue, and “if it feels warm, be sure it is new.” To keep them fresh, “pitch them all with the small end downwards in fine wood ashes, turning them once a week end-ways, and they will keep some months.”

I also marveled at the ambition of Thomas F. De Voe, author of the 1866 edition of ” ‘The Market Assistant,’ containing a brief description of every article of human food sold in the public markets of the cities of New York, Boston, Philadelphia, and Brooklyn.” That’s not even the whole title, because he’s not kidding. This book is like a dictionary for a big city farmers market. You’ll discover that saltwater terrapin were best in November, December and January, and that plaintains and pineapples were available from the Caribbean. Artisans of the day marketed their birch brooms, basketry and beeswax.

‘NEVER CAUSES BLINDNESS’

The cookbooks also veer into the art of using food as medicine. “Invalid cookery” was the precursor to modern-day chicken soup to fight a cold or flu. I found remedies for boils (rub the skin of a boiled egg on them), dysentery, chilblains, warts and bad breath.

I even found – alert the New England Journal of Medicine! – a three-day cure for smallpox in Maine’s first cookbook, “Fish, Flesh and Fowl: A Book of Recipes for Cooking Compiled By Ladies of State Street Parish”: “One ounce cream of tartar dissolved in a pint water, drank at intervals when cold, is a certain, never failing remedy. It has cured thousands, never leaves a mark, never causes blindness, and avoids tedious lingering.”

As the country marched into the 20th century, Americans started taking a more scientific approach, and the claims of such miracle cures were less frequent, Van Der Steenhoven said.

Other changes, too, can be tracked through the cookbook collection. When the “The Frugal Housewife” was printed in Boston in 1772, it was still basically a British cookbook that contained lots of British ingredients. Over time, more American ingredients begin appearing.

“At first there’s not any accommodations being made for the fact that (a cookbook is) being printed in an entirely different country that has an entirely different foodscape,” Van Der Steenhoven said. “But then you have later Hannah Glasse.”

Glasse’s “The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy” was printed in Virginia in 1805 as the “First American edition.” Amelia Simmons came along in 1815 with “American Cookery, or, The art of dressing viands, fish, poultry, and vegetables; and the best modes of making puff-pastes, pies, tarts, puddings, custards, and preserves. And all kinds of cakes, from the imperial plumb to plain cake. Adapted to this country, and all grades of life.”

Simmons’ book includes the first published examples of use of corn, and an early example of pairing cranberry sauce with turkey. The small, simply-made book was published originally in 1796, and by 1830 there were dozens of printings.

“It’s so tiny,” Van Der Steenhoven said. “It’s clearly meant to be tucked into an apron pocket.”

Over the years pheasants became less common in recipes, replaced by the all-American turkey – though the cooking method might still seem odd to those of us living in the 21st century.

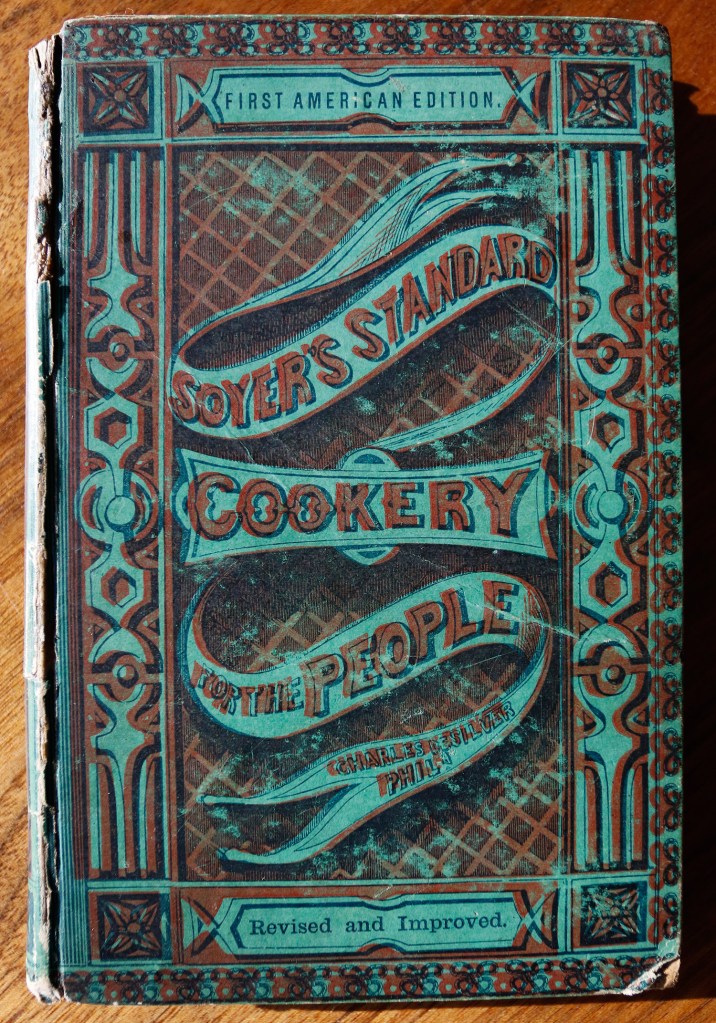

In the first American edition of “Soyer’s Standard Cookery for the People: Embracing an Entirely New System of Plain Cookery and Domestic Economy,” published in 1859, the author describes boiling a stuffed turkey for an hour and a half.

“A turkey done in this way is delicious,” he wrote.

We’ll take his word for it.

Send questions/comments to the editors.