The Internet Archive is a nonprofit digital archive that houses an astonishing collection of material, all downloadable, from Grateful Dead bootlegs to Charlie Chaplin movies to random 20th century software programs. Archive.org is like a flea market in the cloud, without price tags.

Among that ephemera is a treasure trove of more than 18,000 seed and nursery catalogs dating back to the 18th century, all digitized and uploaded by the National Agricultural Library over the last two years. Eventually, the entirety of the Henry G. Gilbert Nursery and Seed Trade Catalog Collection of more than 200,000 catalogs will be available for the public to browse electronically.

These catalogs, many of them beautifully illustrated, are more than just charming – they represent agricultural history. Their pages are littered with lost varieties and clues to how and what we grew in earlier centuries. They’ve always been available to the public, but until being digitized, that meant a trip to the fifth floor of the National Agricultural Library’s building in Beltsville, Maryland, where the originals are stored in an environment carefully controlled to high archival standards.

Now anyone with Internet access can see them. But if it weren’t for a Mainer born in Brunswick in 1878, this collection might not exist at all.

FLOWERS IN THE ATTIC

That Brunswick native, Percy LeRoy Ricker, had both a bachelor’s and a master’s degree from the University of Maine by the time he was 23. By the next year he was a published author of a slim volume called “A Preliminary List of Maine Fungi,” printed by the University of Maine.

The book begins with an apology; Ricker wanted the reader to understand how incomplete it was – it includes only fungi from Cumberland, Androscoggin and Penobscot counties – but wrote that it seemed “advisable to publish it in this condition” because of the need to “call attention to this very much neglected group, and perhaps to stimulate further study.”

There are a tremendous number of fungi listed in this volume. Many, many mushrooms. It doesn’t seem that much of a stretch to suppose that Ricker’s humble apology suggests a completist – the sort of person who aims to collect or see it all. Certainly what he did next seems to indicate he was one.

After Orono, Ricker went on to a long career with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, serving as the department’s first economic botanist in Washington, D.C. His duties included visiting plant nurseries around the country, and on those visits, starting in 1904, he started collecting something other than fungi: old seed and nursery catalogs. Ricker was inspired by the librarian for the Massachusetts Horticultural Society, who had several thousand of the catalogs in his own collection and was willing to share duplicates, jumpstarting Ricker’s collection.

The catalogs represented a sort of history of cultivating plants. And more: Price and distribution trends. Landscaping developments. Hybridization efforts.

Ricker poked around in the attics of old seed companies and nurseries, looking for duplicates they wouldn’t mind giving him. In some cases, if no duplicates were available, he’d photograph the originals. When he discovered the family that started what may have been the nation’s first large-scale commercial nursery had old nursery broadsheets dating back to 1771 stashed in the family homestead, he arranged to have them photographed. He asked all the seed companies and nurseries he visited to start sending their annual catalogs to the USDA.

By 1926, he had amassed 34,000 catalogs. They took up 430 feet of shelving. By 1945, a few years before his retirement, there were 70,000 seed and nursery catalogs in the Department of Agriculture’s Library including some from Europe, South America, Asia, Australia, Africa. Percy Ricker left his mark. The collection as it stands now, about three times the size of what he collected, is named for Henry G. Gilbert, a reference librarian at the USDA’s library and the longtime curator of the collection. According to the National Agricultural Library, when the library was shifting priorities in the 1980s, Gilbert was passionate that the seed catalog collection be preserved.

Ricker wrote about the collection just before his retirement, referring to its research potential. The catalogs pose an entry point for botanists, biologists and other scientists studying plants and their commercial history. At UMaine today, the Raymond H. Fogler library has a special collection of its own, two boxes of seed catalogs, many very old, that were collected and donated by Iva Burgess, who was on the biology staff of the Agricultural Experiment Station.

Interest in that collection has increased, said special collections librarian Desiree Butterfield-Nagy. “We’ve had classes that have come in to look at invasive (plant) species to see how they were marketed initially.”

“We would love to have these scanned,” she added.

CONSUMMATE CABBAGE

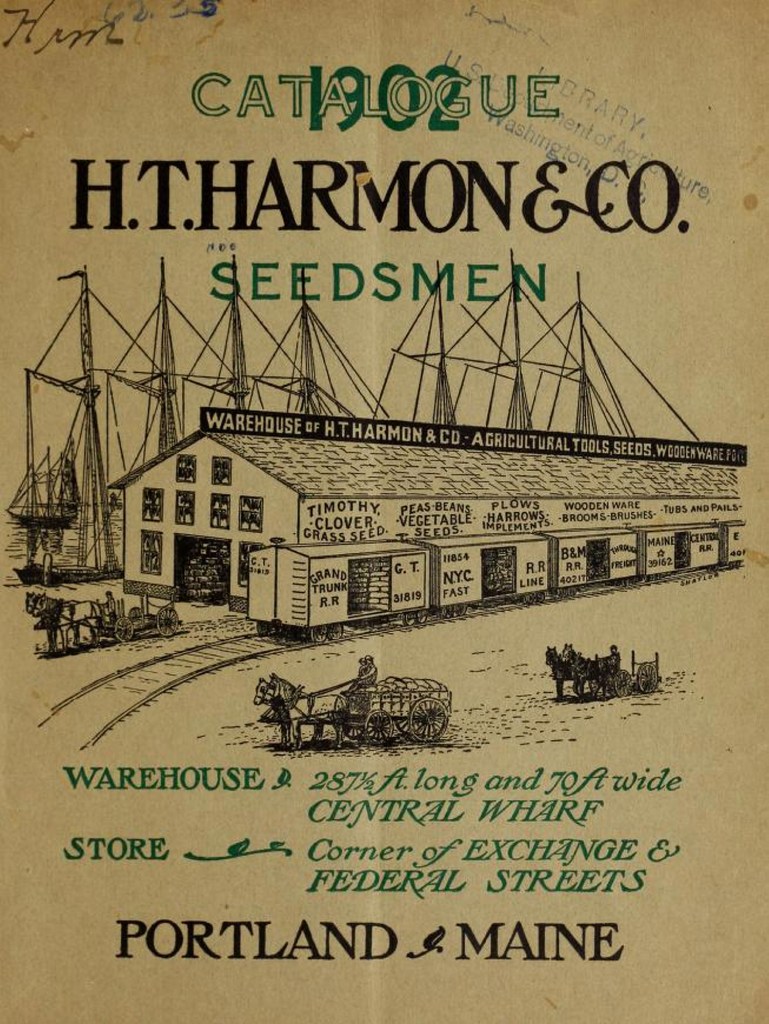

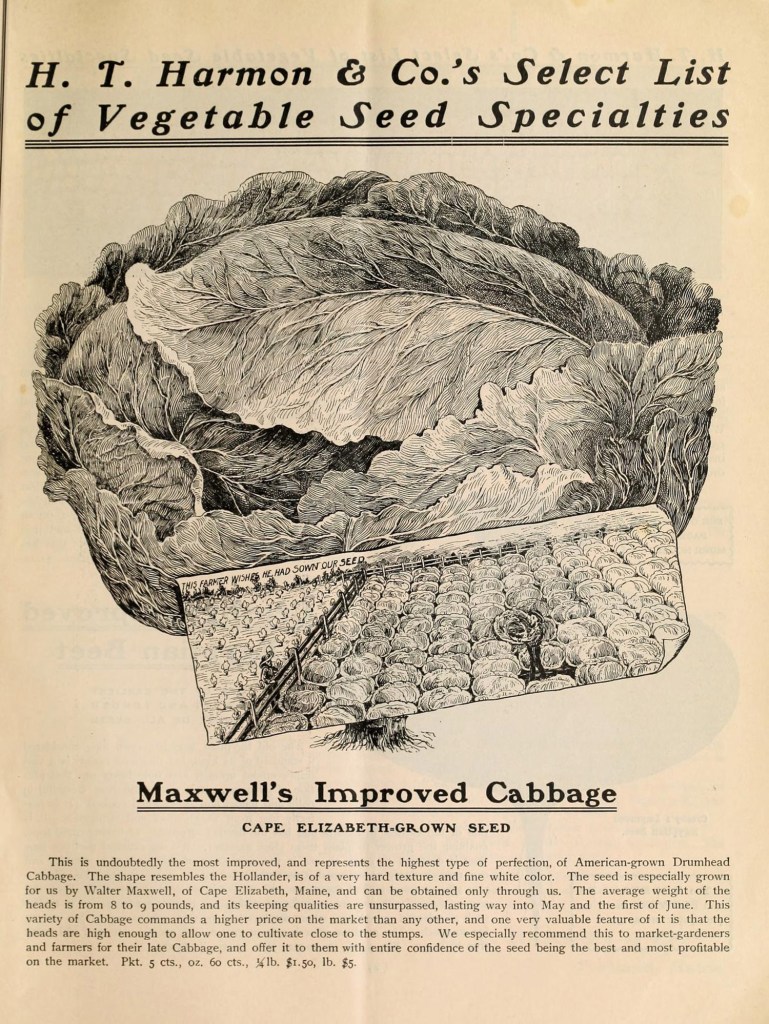

Ricker lived to be 94, but probably not long enough to even imagine how the collection he started might reach the world some day, modern technology delivering the past. Type in “Maine” in the search feature of the Henry G. Gilbert Collection at archive.org and one of the first images that comes up is Portland-based H.T. Harmon & Co. Seedsmen’s catalog of 1902. Turning over the cover electronically reveals a glowing endorsement of seed for a very special vegetable, “Maxwell’s Improved Cabbage” apparently capable of growing to nine pounds and representing “the highest type of perfection.” A pound of seed went for $5, and H.T. Harmon & Co. promised this cabbage would last in storage until the first of June. The farmer who produced this seed? Walter Maxwell of Cape Elizabeth.

There’s a picture, or rather, an engraving of said cabbage and an accompanying sketch of rows of the vaunted cabbages growing in one field while an envious farmer looks over from his sad, Maxwell-less field.

The Maxwells still farm in Cape Elizabeth. Lois Bamford, who is the sixth generation to own Maxwell’s Farm (along with her husband, Bill) said Walter was her great great grandfather. Family lore has it that he was known as the Cabbage King.

While the Bamfords no longer grow cabbage on Maxwell Farm, Lois Bamford’s father did. “We used to have cabbage stored in our cellar and they’d trim it throughout the winter,” she said. But in that era, iceberg was the trendy green in Cape Elizabeth. Until a reporter called her, she didn’t know about her forefather’s “improved cabbage” but after looking at the H.T. Harmon catalog online, she wrote to say she’d be downloading the artwork for framing.

LOST AND FOUND ARTISTS

H.T. Harmon & Co. had a warehouse on Central Wharf and a store at the corner of Exchange and Federal in Portland. There’s a sketch of the warehouse on the cover, which includes a signature, barely visible under a railroad car being loaded. It’s Shaylor, presumably for either Horace Shaylor Jr., who started an engraving company on Middle Street or less likely, his sister Luella, an artist who specialized in miniatures.

The signature is unusual – most catalogs were jammed with artwork, likely engravings, but few were signed.

“There is all this great, great line art that has been totally forgotten,” said Gene Frey, who has been designing and producing Fedco’s catalog ever since the Clinton-based company first put one out. Fedco’s catalog is the contemporary seed catalog that most closely resembles the 19th century catalogs (the other major Maine-based seed company, Johnny’s Selected Seeds, uses color photography). As such, Frey has become something of a student of the line art from the original seed company catlogs.

Rarely has Frey seen a signature in the old catalogs, but he’s seen the initials A.E. on a number of sketches. “To this day I don’t know who that was,” Frey said.

Frey became intrigued by old catalogs for highly practical reasons.

“Fedco needed cheap graphics,” he said, with a laugh. One of the best sources were images old enough for the copyright to have run out – some of which he found in old agriculture books in the Colby library. On his quest for new images, he became an eBay afficiando, snapping up old catalogs.

He built a Fedco archive, paying $30 to $50 for the catalogs. Then collectors discovered the market and “the prices started jumping.” Once prices passed into the “hundreds, I just said, ‘OK, I am out of here.’ ” These days Fedco uses about half vintage art in its catalog and half new sketches made by employees and friends – including artwork by Frey himself. He’s delighted to have a new source at archive.org, especially for Maine-related material.

“I never had a chance to go somewhere and say, ‘who are the Maine seed companies?’ ”

HOME-STATE ADVANTAGE

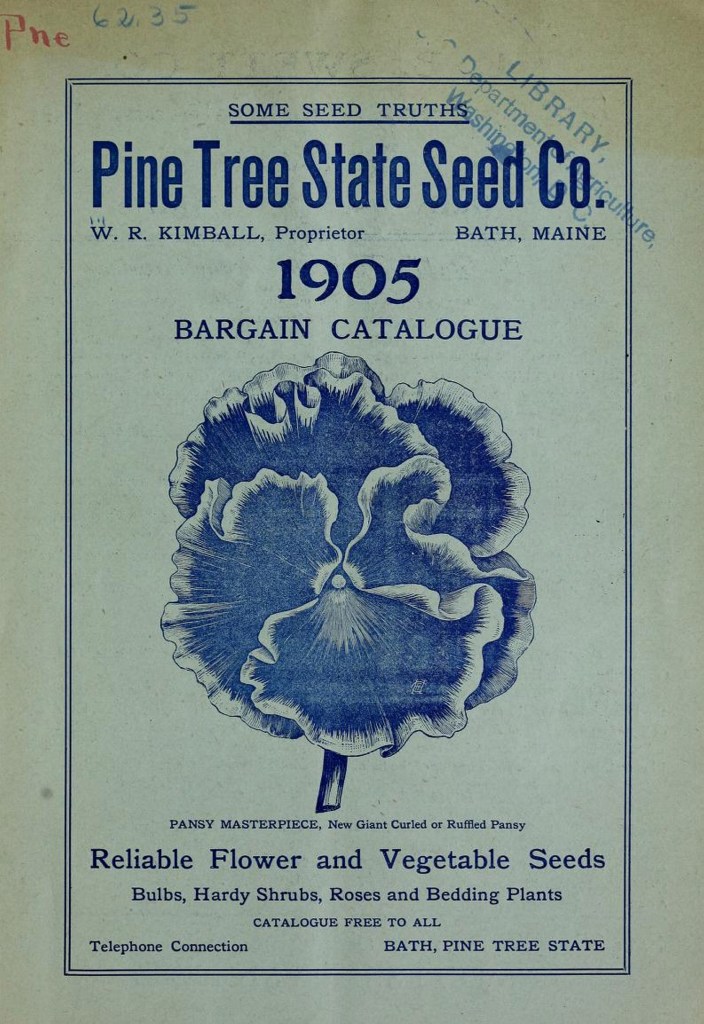

It is hard to say whether Percy Ricker collected more catalogs from his home state than from other places. The archives contain records, not all digitized yet, of Donald Chandler’s New Gloucester-grown strawberry plants and gladiolus seedlings, Houlton-based E. L. Cleveland Company’s Aroostook-grown seed potatoes of 1910 and 23 years worth of catalogs from Haskell Implement and Seed Co. of Lewiston. From Ricker’s hometown, there is Roseholme Gardens of Brunswick, which offered perennial and bulb seed, and from neighboring Bath, the Pine Tree State Seed Company’s bargain catalogs of 1904-1907.

Of those, only the last name lives on – in a way. Jeff Wright and his wife Melissa Emerson run Pinetree Garden Seeds in New Gloucester today, an entirely unrelated company. They cater to home gardeners who want smaller, packets of seeds appropriate for raised beds and small spaces.

What’s particularly fascinating about the Henry G. Gilbert collection is the window it provides into a vibrant past that has mostly disappeared. Seed sales are far more centralized today. In Maine, they are ruled by Fedco and Johnny’s, which have replaced dozens of companies whose names have been forgotten but which helped build cities.

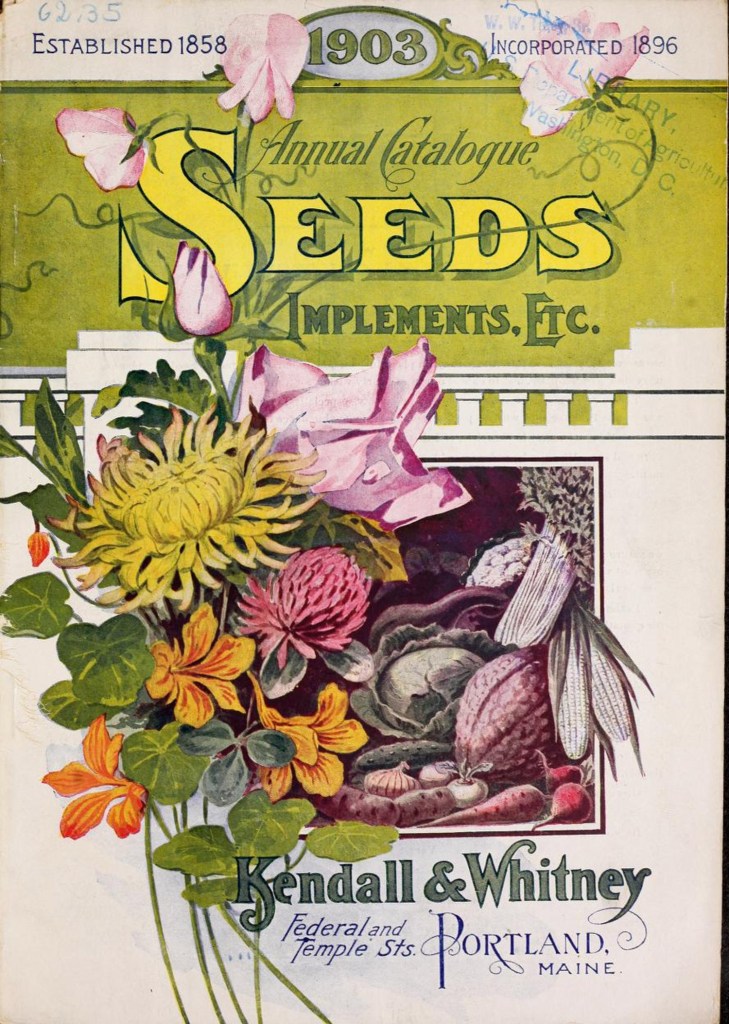

The best example of this is Kendall & Whitney, a Portland company started in 1858 by Ammi Whitney, a farm boy from Falmouth, and his partner Hosea Kendall. Of the Maine catalogs available on Archive.org, the collection of Kendall & Whitney’s catalogs is the most impressive, full color in many cases and extensive.

Whitney left Maine as a young man, trained at a Boston seed house for six years, then returned and teamed up with Kendall to open what became Maine’s largest seed and agricultural implement company. It was an opportune time to get into the business. Maine’s agricultural economy was thriving and the old method of acquiring seeds from Shaker peddlers – they invented the sale of seeds in packets – was being replaced by mail order. The two men started their business in what had been the City Hall (in what is now Monument Square).

Kendall & Whitney expanded and in 1888, built a new brick building at the corner of Federal and Temple (now the parking lot for the Post Office). Based on the spectacular still extant brick mansion Whitney built himself in the West End at the corners of Neal and Spring streets, the agricultural merchants thrived.

The cover art on these catalogs ranges from the lushly illustrated (1894) to the much more modest (1895 and 1896) then back again into brighter imagery (1897). Was this because Whitney’s partner Kendall died in 1895? Perhaps. Kendall’s name remained on the company masthead. Now all that remains of the company is old paper and the art and information on them.

Like the price of price of a packet of Forget-Me-Nots. Five cents in 1909, shipped to you from Portland, Maine.

Send questions/comments to the editors.