David Bowie, the self-described “tasteful thief” who appropriated from and influenced glam rock, soul, disco, new wave, punk rock and haute couture, and whose edgy, androgynous alter egos invited fans to explore their own dark places, died Sunday. Bowie had turned 69 on Friday, the same day he released his latest album which was entitled “Blackstar.”

The cause was cancer, said a representative.

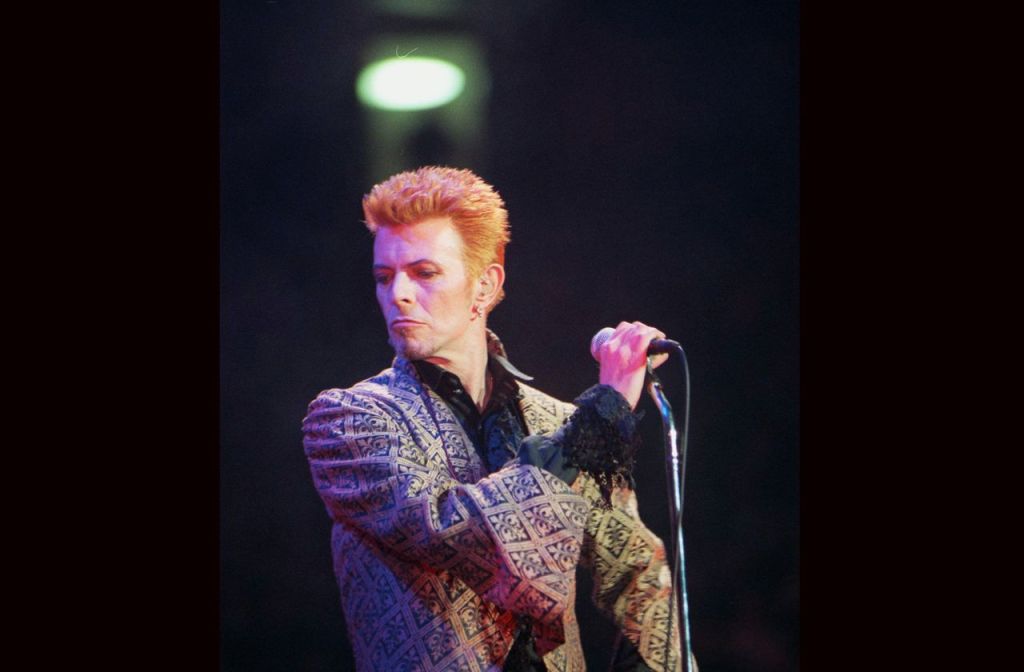

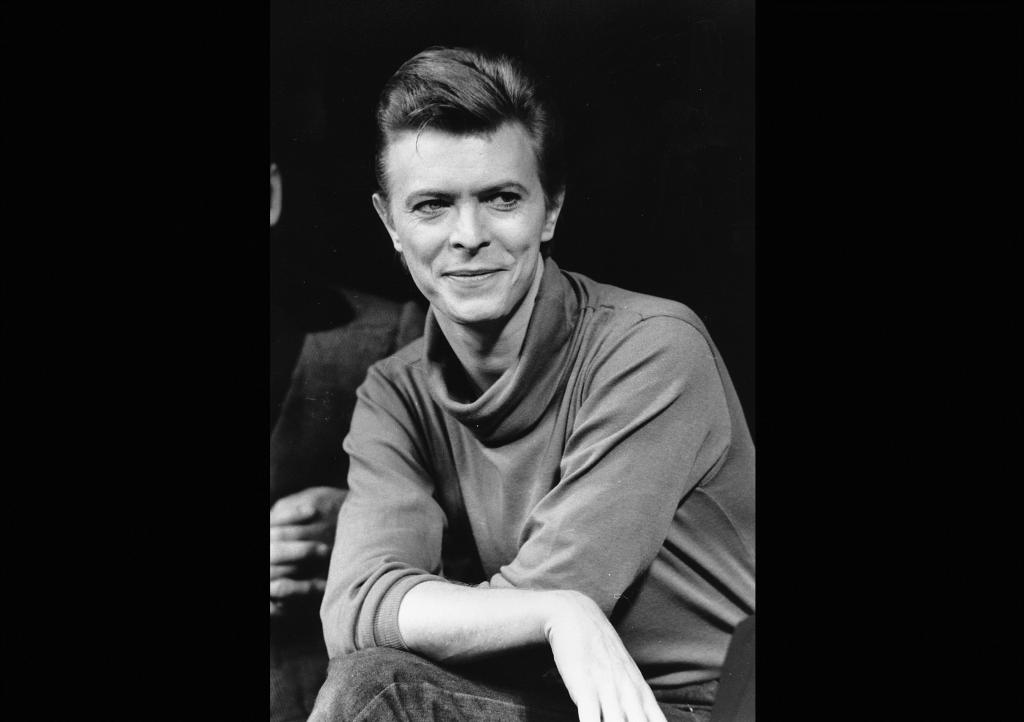

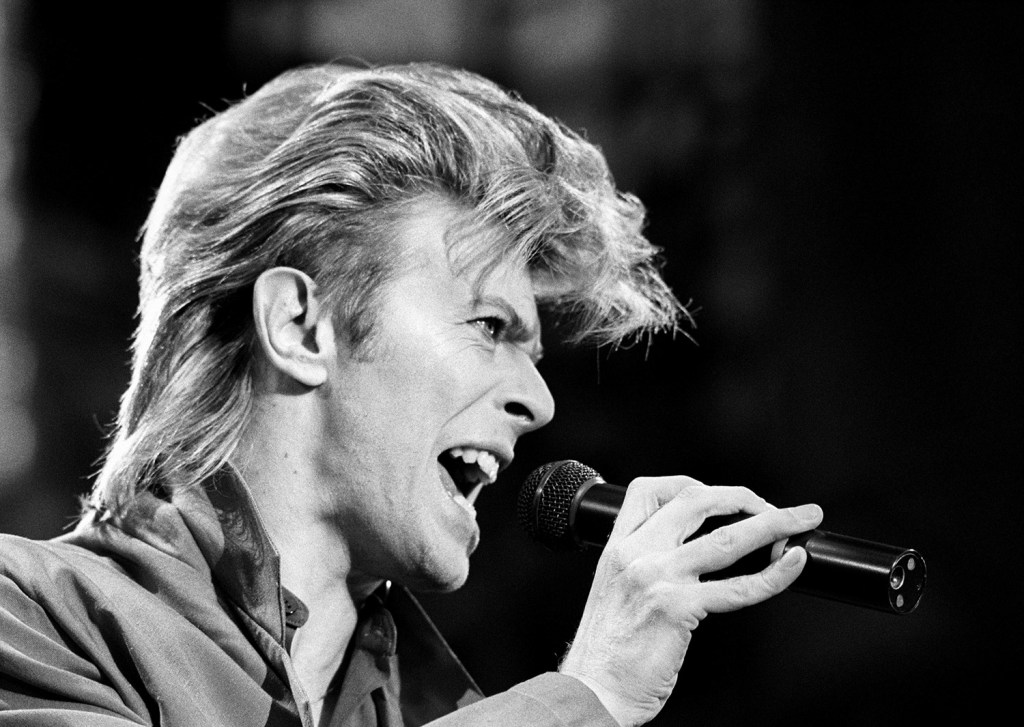

With his sylphlike body, chalk-white skin, jagged teeth and eyes that appeared to be two different colors, Bowie combined sexual energy with fluid dance moves and a theatrical charisma that mesmerized male and female admirers alike.

Citing influences from Elvis Presley to Andy Warhol – not to mention the singer Edith Piaf and writers William S. Burroughs and Jean Genet – Bowie was trained in mime and fine arts, and played saxophone, guitar, harmonica and piano. A scavenger of musical and visual styles, he repackaged them in striking new formats that were all his own, in turn lending his dramatic, gender-bending aesthetic to later performers such as Prince and Lady Gaga.

With “a melodic sense that’s just well above anyone else in rock & roll,” the singer Lou Reed once wrote, “David Bowie’s contribution to rock & roll has been wit and sophistication.” His output between 1969 and 1983 made up “one of the longest creative streaks in rock history,” according to Rolling Stone magazine.

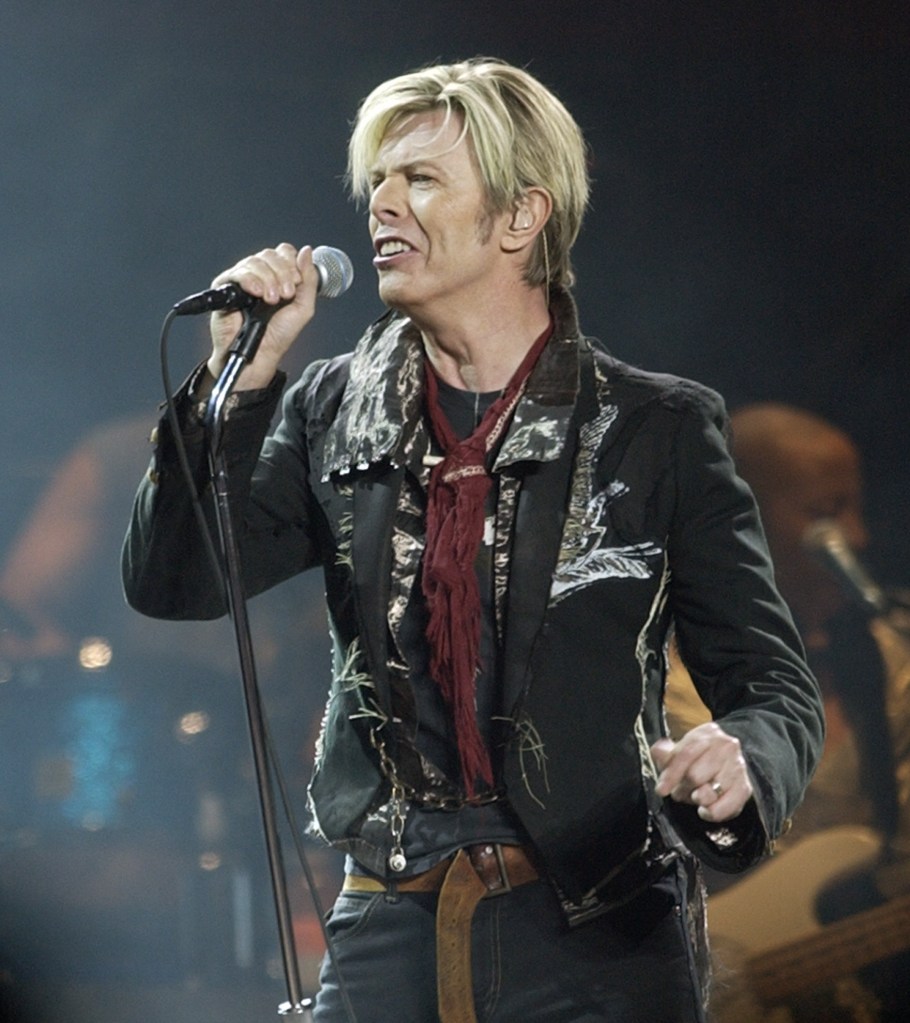

By the height of his fame in the early 1980s, Bowie had enacted his own death repeatedly, in the form of characters and ensembles he would create, inhabit and then discard. “My policy has been that as soon as a system or process works, it’s out of date,” he said in a 1977 interview. “I move on to another area.”

The practice, which extended to friendships and professional partnerships, could be jarring. The Spiders From Mars, his band during his glitter-rock Ziggy Stardust years, learned that they were being fired when Bowie announced it onstage at the end of a 1973 tour.

To fans as well, Bowie’s rapid transitions could feel like whiplash. In the space of five years he was a curly-haired folk singer; a Lauren Bacall look-alike in an evening gown; a vampiric creature with a red mullet, shaved eyebrows and a skintight, multicolored bodysuit; and a coked-up dandy in a tailored suit, suspenders, fedora and cane.

Some of these looks had alter egos associated with them, such as Ziggy Stardust, a fictional rock star who is ultimately ripped to pieces by his fans, or the Thin White Duke, a spectral, disaffected figure dressed impeccably in cabaret-style evening wear who throws “darts in lovers’ eyes.”

As much curator as inventor, Bowie lifted melodic motifs from blues, funk and standards and presented them in such a way that many fans had no idea that the catchy “Starman” was a version of “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” or that the melancholy “Life on Mars” was “My Way” in disguise. Other musical borrowings were more obvious, such as the opening bass line of “Jean Genie,” taken from “I’m a Man,” or the “On Broadway” reference at the end of the title track of the album “Aladdin Sane.”

Stardom gave Bowie his pick of talent. He hand-selected virtuoso session players to help define each musical phase: Mick Ronson’s guitar solos, Mike Garson’s dissonant piano improv, Carlos Alomar’s funky rhythms, and the techno sounds of guitarists Adrian Belew and Robert Fripp that permeated his work in the late ’70s and set the stage for the European electronica of the 1980s.

Bowie’s voice was similarly labile – gliding between ragged cackle and haunting croon as he sang about decaying cities and alienated rock stars. Fellow musicians marveled at his ability to seduce a crowd with a look or a gesture.

“He’s the total artist,” said Nicholas Godin of the duo Air. “The look, the voice, the talent to compose, the stage presence. The beauty. Nobody is like that anymore. Everybody is reachable; he was unreachable.”

David Robert Jones was born on Jan. 8, 1947, in Brixton, a working-class south London neighborhood scarred by World War II bomb blasts.

His father, a publicist for a children’s charity, was a failed music hall impresario; his mother was a former waitress and model. An older half-brother, Terry, was diagnosed with schizophrenia and institutionalized when Bowie was a young man. For many years the rock star worried about his own mental health, and the theme of insanity runs through his early songs.

“I used to wonder about my eccentricities, my wanting to explore and put myself in dangerous situations, psychically,” he told Esquire magazine in 1993. “I was scared stiff that I was mad, that the reason I was getting away with it was that I was an artist, so people never knew I was totally bonkers.”

His family moved to the middle-class suburb of Bromley, where young David attended Bromley Technical High School and found a mentor in art teacher Owen Frampton, father of the future pop star Peter. At 14, in a fight with a friend over a girl, David was punched in the eye, resulting in a permanently dilated left pupil that would add to the otherworldly appearance he would later cultivate.

After a few lessons on a plastic saxophone purchased on a payment plan, he began playing in local bands, finding that he liked singing and the female adulation that came with it. To avoid confusion with Davy Jones of the Monkees, he renamed himself after the 19th-century American frontiersman and the hunting knife associated with him.

Fascinated by musical theater, Bowie joined a mime troupe led by the dancer (and, briefly, his lover) Lindsay Kemp, who taught him the extravagant, stylized movements he would later bring into his own stage performances.

Although his first two albums received little notice, in 1969 Bowie had his first hit single with “Space Oddity,” a song about a disaffected astronaut who decides to remain “sitting in my tin can, far above the world,” rather than return to life on Earth. Released five days before the Apollo 11 launch, it reached No. 5 in Britain.

That year he also met Angela Barnett, with whom he would enter into a 10-year marriage and have a son, Duncan Zowie Haywood Jones, born in 1971. A shrewd manager of her husband’s early career, Barnett tolerated his blatant philandering and gave him the spiky-on-top, long-in-the-back haircut that would become his signature look through the early 1970s.

The hairdo – and the accompanying glittery bodysuits, platform boots and face paint – was intended as a statement against the peace-and-love, denim-clad hippie imagery dominating rock culture at the time. Bowie instead presented fans with cut-and-paste lyrics about the end of the world, and shocked them by dropping to his knees to perform mock fellatio on Ronson’s electric guitar or telling an interviewer he was bisexual (though he would later say that was just an experimental phase).

“We wanted to manufacture a new kind of vocabulary,” Bowie told NPR’s Terry Gross in 2003. “And so the so-called gender-bending, the picking up of maybe aspects of the avant garde and aspects of, for me personally, of things like the Kabuki theater in Japan and German expressionist movies, and poetry by Baudelaire . . . it was a pudding of new ideas, and we were terribly excited, and I think we took it on our shoulders the idea that we were creating the 21st century in 1971.”

His ever-changing, outrageous personae also served to mask the painful shyness and insecurity of his younger years.

“I didn’t really have the nerve to sing my songs onstage,” he told Musician magazine in 1983. Referring to the various personae, he said: “I decided to do them in disguise so that I didn’t have to actually go through the humiliation of going onstage and being myself. I continued designing characters with their own complete personalities and environments. I put them into interviews with me! Rather than be me – which must be incredibly boring to anyone – I’d take Ziggy in, or Aladdin Sane or the Thin White Duke. It was a very strange thing to do.”

Along with his own music, he promoted the careers of lesser-known musicians such as Iggy Pop, Lou Reed and Mott the Hoople, whose signature hit, “All the Young Dudes,” was written by Bowie. In 1974 he moved to Los Angeles, whose hyped-up, drugged-out music scene – the “Fame” and “Fascination” immortalized on his album “Young Americans” – took a toll. Extensive cocaine use made him jittery and paranoid, even as it enabled him to be creatively prolific.

Seeking calm and anonymity, Bowie spent much of the late 1970s in West Berlin, where in collaboration with Brian Eno he produced three albums that experimented with ambient sound and presaged the synthesizer-heavy music of the 1980s.

Returning to live in New York City, he began expanding his range as an actor. Having starred in the 1976 Nicholas Roeg film “The Man Who Fell to Earth,” in 1980 he played the lead in a stage production of “The Elephant Man,” for which Variety praised his “charismatic personality . . . suggesting springs of passion beneath the severe physical handicaps of the character.”

In both roles he played sensitive freaks misunderstood by the society around them, a theme that had also permeated much of his music. He also starred in “Just a Gigolo” with Marlene Dietrich (1978), in the Tony Scott vampire film “The Hunger” with Catherine Deneuve (1983) and as a rebellious prisoner of war in “Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence” (also 1983).

Bowie’s commercial musical pinnacle also came in 1983, with the blockbuster album “Let’s Dance.” It blasted him into international superstardom, though critics complained that it lacked the depth of his earlier work. Its unexpected success threw Bowie into a creative tailspin. Having planned to follow it with more esoteric material, he instead tried to duplicate the “Let’s Dance” success with albums that were critical flops.

“I suddenly felt very apart from my audience,” he told Live magazine in 1997. “And it was depressing, because I didn’t know what they wanted.”

Bowie regularly released albums through the 1980s and 1990s, although none approached the success of his previous output. But he continued to innovate, in 1996 becoming the first musician of his stature to release a song, “Telling Lies,” exclusively via the Internet. He caused a sensation when he was the first to sell asset-backed bonds, known in his case as “Bowie bonds” and acquired by Prudential, tied to the royalties on his back catalogue.

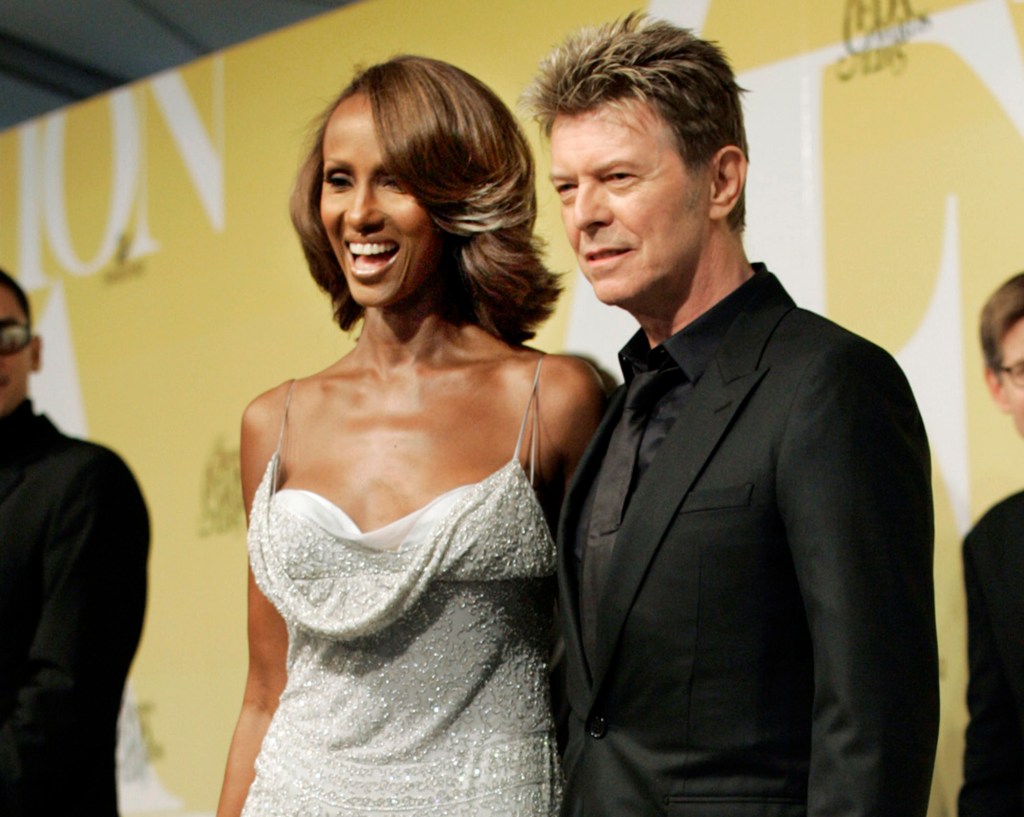

By the eve of the century he had once aspired to create, Bowie seemed to be finally settling down. He fell in love – a condition his younger self had pooh-poohed – with the model Iman Abdulmajid, whom he married in 1992 and with whom he had a daughter, Alexandria Zahra Jones, in 2000. After suffering a heart attack backstage during a tour in 2004, he stopped producing albums or touring for nearly a decade, devoting himself to family life. He even got his vulpine teeth capped, to the disappointment of some fans.

But in 2013, the same year an elaborate retrospective of his visual legacy began touring the world, the 66-year-old Bowie released a new album, recorded in secret, called “The Next Day.” His first album in a decade and the 24th of his career, it was praised by critics, who called it innovative even as it hearkened back to his early music.

That Bowie was still reinventing himself in his seventh decade could not have surprised those who knew him. “David’s a real living Renaissance figure,” Roeg told Time magazine in 1983. “That’s what makes him spectacular. He goes away and re-emerges bigger than before. He doesn’t have a fashion, he’s just constantly expanding. It’s the world that has to stop occasionally and say, ‘My God, he’s still going on.’ “

Send questions/comments to the editors.