Friday is not only the first day of a new year, but also the day when some of Maine’s lowest-paid workers get a raise.

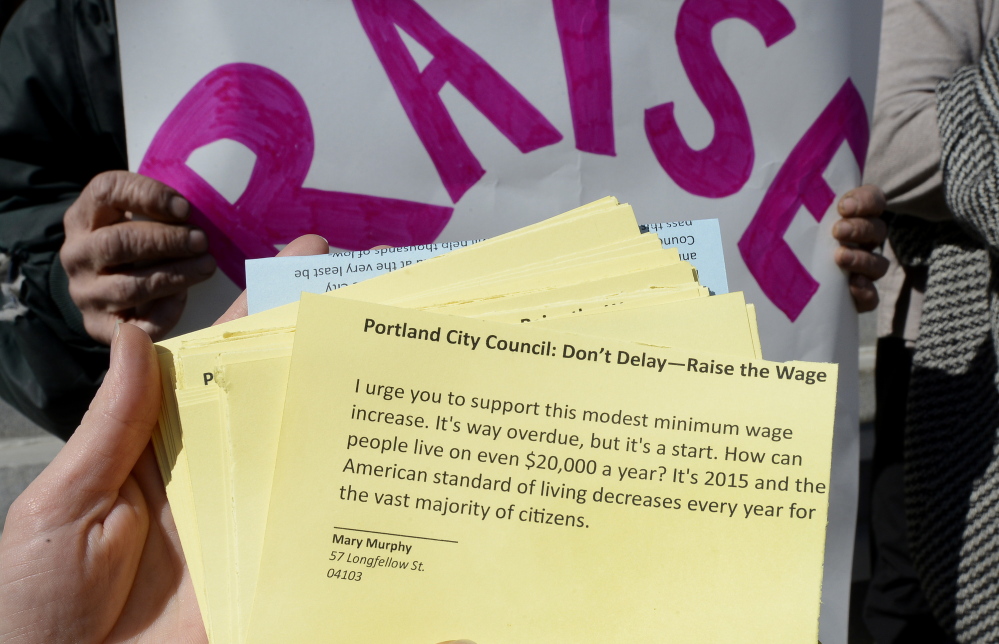

In 2015, the Portland City Council passed an ordinance that bumps up the city’s wage floor from $7.50 an hour to $10.10, effective Jan. 1. It may not have gotten as much attention as the citizen-initiated $15-an-hour citywide minimum-wage proposal that was ultimately defeated at the polls in November, but it is a solid step toward economic justice in Maine’s biggest city. And it should explode some myths about the dangers of a higher minimum wage just in time for voters to go to the polls to approve a statewide $12 minimum wage next fall.

The minimum wage was created by federal law, and keeping it in line with the cost of living used to be a job for Congress. But starting in the 1980s, the minimum wage was allowed to decline in buying power, and the partisan divide in Washington has made meaningful increases politically impossible.

The situation has become intolerable during the last few years: Soaring productivity and declining unemployment rates did not drive up wages, which are flat or falling against inflation.

At an increasing rate, cities like Portland have stopped waiting for relief from the federal government and passed their own minimum wages. Two cities raised their own minimum wages in 2012, five in 2013, 12 in 2014 and 14 in 2015 – including not only Portland but also Bangor, where the increase is contingent on the statewide minimum-wage vote next fall. If the statewide initiative fails, then Bangor will increase its minimum wage by 75 cents each year for three years, beginning Jan. 1, 2017.

The word from the early adopters has not borne out the predictions of minimum-wage naysayers. In Seattle-Tacoma, Washington, the first area to implement a $15 minimum wage in the hospitality and travel industries, unemployment hit a eight-year low of 3.6 percent, significantly lower than the state jobless rate of 5.3 percent. The Puget Sound Business Journal reported that in the first six months after the city of Seattle separately raised its minimum wage (for all workers), starts of new restaurants exceeded the same period a year earlier.

There is no evidence that it was the minimum wage that boosted the local economy, but there is also none for the warnings that businesses would close, relocate and shed employees.

If Portland mirrors the national figures assembled by the Congressional Budget Office, an increased minimum wage will put money into the hands of people who need it most.

Far from being a starting wage for teenagers with after-school jobs, the majority of minimum-wage workers are adults who work full time, with about two-thirds older than 25. More than half are women, and more than a quarter have children. Nearly 40 percent of working, single mothers earn the minimum wage.

Money put into the hands of these workers will be spent on food and rent, which would be good for local businesses. It will also reduce pressure on state and local social services. And raising the minimum wage will put upward pressure on wages that are close to the new minimum.

Portland’s ordinance is not perfect: It keeps the tipped wage at the state level of $3.75. Servers will still be covered by the new minimum wage, but it will be up to them to prove to their employer that their tips and hourly wage did not add up to an average of $10.10 an hour.

But the city has taken a positive step in the right direction, and the whole state should consider following.

Send questions/comments to the editors.