KENNEBUNK — A Kennebunk electric utility is weighing whether to remove the three lowest dams on the Mousam River or face potentially costly upgrades to restore fish passage to a river that once hosted large runs of spawning fish.

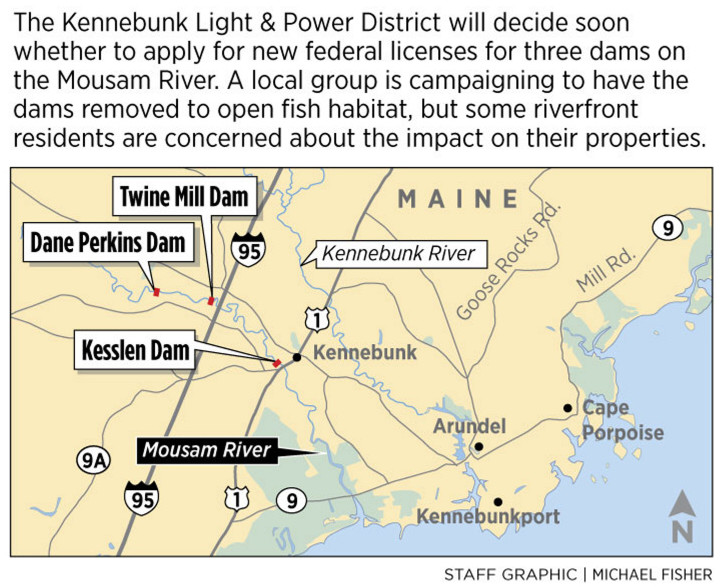

Trustees at Kennebunk Light & Power District have until March 2017 to decide whether to seek federal relicensing of three dams that the nonprofit utility owns on the Mousam River or propose several alternatives for the facilities. One option under serious consideration – and being pursued by local conservationists and sportsmen – is the removal of some or all three of the dams, including the large Kesslen Dam located in the heart of downtown Kennebunk.

The Mousam River is the only major river system in Maine emptying into the Gulf of Maine that lacks any methods for fish such as American shad, alewives or Atlantic salmon to bypass the dams, effectively blocking them from accessing more than 300 miles of watershed. Removing the three dams would allow the lower 9 miles of the Mousam River to flow freely – although an additional 12 dams remain on the upper stretch of river – and is part of an intense river restoration push in Maine.

“It’s become very clear that the dams on the river – and particularly the three dams in Kennebunk – are having a dramatic impact on everything from water quality to fisheries” and other wildlife habitat, said John Burrows, a member of the Mousam and Kennebunk Rivers Alliance and New England program director for the Atlantic Salmon Federation.

MUCH CHEAPER TO REMOVE DAMS

After two years of review, Kennebunk Light & Power released a 90-page draft assessment that concluded that relicensing the Kesslen, Twine Mill and Dane Perkins dams would cost between $8.8 million and $11.7 million. Much of that cost would be consumed by installing fish ladders or other methods of fish passage that are currently absent under the dams but likely would be required in order to receive a new license from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission.

Surrendering the licenses and removing the dams, by comparison, was estimated to cost $2.3 million and would carry fewer long-term obligations for the utility. But Kennebunk Light & Power would need to replace the estimated 600 kilowatts of electricity generated by the facilities – typically just a small percentage of the utility’s electricity supply – likely by purchasing it from other sources. And riverfront homeowners have raised concerns about how the lower water levels at impoundments will affect their property values, about the release of contaminated sediments and whether the changes would worsen flooding risks.

“Many factors are being taken into consideration as part of the board’s decision-making process,” Kennebunk Light & Power’s board of trustees said in the October report. “The board is weighing environmental, economic and financial factors in order to make the decision that is in the best interest of our ratepaying customers.”

A utility official could not be reached for comment Monday. The next step in the process is expected to occur Jan. 12, when the board solicits additional feedback on the options.

RESIDENTS DIVIDED ON DAM REMOVAL

On Monday, Kennebunk resident Bill Grabin stood near the third dam, the Dane Perkins facility, located on a quiet stretch of water about 3 miles upriver from downtown Kennebunk. Water cascades over the 10-foot-tall, 50-foot-wide dam and gently flows through a landscape lined with trees but few houses. Although the smallest of the three lower dams, the Dane Perkins creates an impoundment that extends more than 7 miles upriver to the much-larger Old Falls Dam, which is not owned by Kennebunk Light & Power.

An active member of the Mousam and Kennebunk Rivers Alliance, Grabin talks excitedly about the prospects of a free-flowing river below the Old Falls Dam and believes the removal of all three dams makes sense from economic, environmental and recreational standpoints.

“Many people are thrilled with the idea of being able to go from Old Falls to the sea,” Grabin said.

Kennebunk Light & Power received more than 90 pages of written comments from dozens of local residents on the issue, the vast majority in support of removing the three lower dams. One of the top concerns raised by property owners near downtown Kennebunk, however, was that the removal of the 14-foot-tall dam and spillway that stretch for more than 100 feet across the river at the site of the Kesslen Mill building would harm property values by eliminating the impoundment behind the dam.

That concern has been raised before with other dam removal projects in Maine – such as Augusta’s Edwards Dam and the historic Penobscot River restoration north of Bangor – and with projects elsewhere around the country. While supporters often point to studies showing that free-flowing rivers often increase property values over impounded rivers, they acknowledge that is not always true. And numerous property owners along the Mousam near downtown Kennebunk expressed fears that the changes would hurt their home’s value.

Among them was Stuart Bowen, who also raised concerns that an unimpeded river would “scour” and undermine the soft soils in the embankments that form part of his backyard and those of several neighbors on Pleasant Street. He also said he does not see how removing the impoundment so clearly visible from his backyard could benefit his property value.

“Every homeowner knows what aspects of their property and surrounding area contribute to the asset value of their property,” Bowen wrote to the utility trustees. “There is no question that my value would decrease. I would expect that all of my neighbors, and perhaps others, would feel the same way.”

EXAMINING THE ECONOMICS

Several riverfront landowners have urged the board to remove the Twine Mill and Dane Perkins dams while decommissioning – but not removing – the Kesslen Dam.

Burrows said the economics don’t support building fishways around the dams and predicted that his organization, and others, would be able to raise money to help remove the dams, thereby further lowering the financial impact on utility ratepayers.

“I don’t think a lot of people are going to want to spend millions of dollars to keep an obsolete dam so a few people can have mill ponds behind their homes,” Burrows said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.