Mike Duddy has heard the eerie sound of winter moth caterpillars ravaging the leaves of oak trees during springtime hikes on Cape Elizabeth’s greenbelt trails.

If Duddy is correct about the potential impact of recent warm December days, that sound could be more noticeable next spring in many coastal Maine communities, especially in Cumberland County, where the non-native moth defoliated more than 10,000 acres last spring, according to the Maine Forest Service.

First identified in Maine in December 2011, winter moths appear to be back in full force this season, with increased sightings reported in Cape Elizabeth, on Casco Bay islands and elsewhere, officials say. Thousands of the small, tan moths have been spotted after dark in recent weeks, fluttering near lighted windows, doorways and lampposts, possibly lending credence to Duddy’s concern.

The chorus of crunching breaks out in May and June, when the caterpillars hatch from eggs laid by moths the previous winter. Duddy, Cape Elizabeth’s tree warden, was walking his dog when he heard the distinct sound as he passed through an infested area. It stopped him in his tracks.

“I’m not joking,” Duddy said. “If you stop along the greenbelt trails and listen, you can hear them munching. Millions of them. It’s a subtle background noise, like light rain falling on leaves.”

A licensed forester and arborist, Duddy worries that the recent stretch of temperatures in the 40s and 50s will rev up the winter moth’s mating season and result in a widespread defoliation next spring.

Duddy saw significant defoliation in the spring of 2013, after a relatively mild December 2012. Less defoliation in 2014 and 2015 followed stormier Decembers in 2013 and 2014 that brought freezing temperatures and measurable snow.

“My fear is that this December has been so warm and mild, it’s a great weather for the moth to flourish and result in great caterpillar activity next spring,” said Duddy, who’s also a health care lawyer.

Duddy admits his concern is based on anecdotal evidence rather than research, but entomologists are still learning about the nondescript moth that was introduced into North America from Europe in the early 1900s. Duddy also notes that it’s unclear what impact the recent introductions of parasitic flies, which feed on winter moths, will have on future infestations, although any related reduction in the moth population is expected to take years.

“We don’t know everything there is to know about this insect,” said Colleen Teerling, a state forest entomologist. “The ground isn’t frozen yet, so they can still emerge and fly and mate.”

RECENT ARRIVAL, GROWING PEST

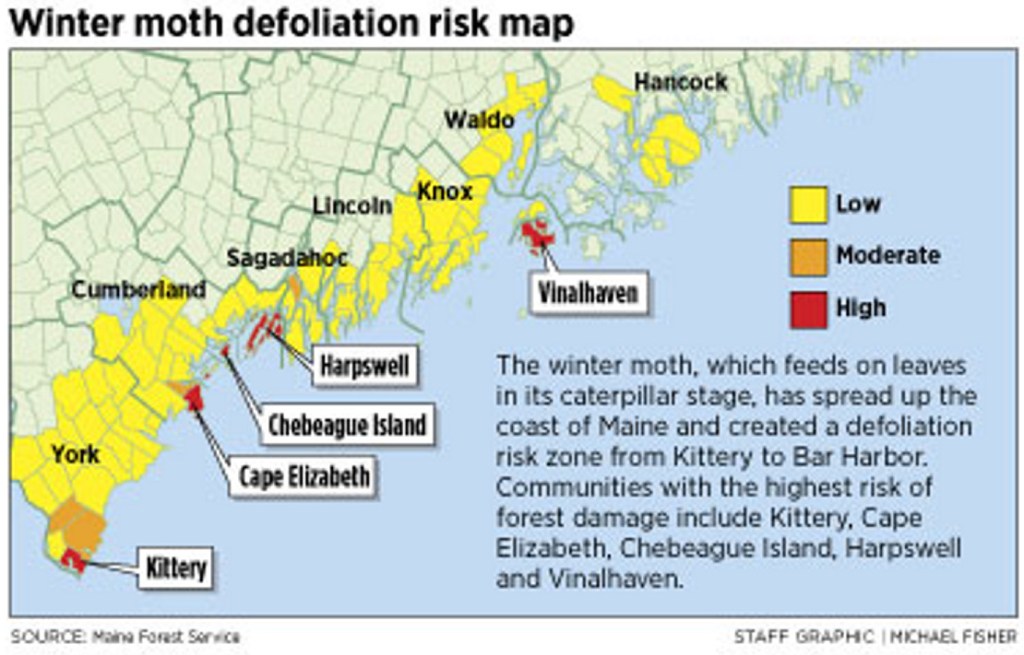

Winter moth infestations were first seen in Nova Scotia in the 1930s and then in the Pacific Northwest – British Columbia, Oregon and Washington – in the 1970s, according to the Maine Forest Service. The moths arrived in Massachusetts in the early 2000s and have spread south into Rhode Island and north along the Maine coast, from Kittery to Bar Harbor.

Entomologists believe the moths may have been brought into Maine by Massachusetts residents when they transplanted perennial flowers and shrubs from infested gardens in that state to homes here.

Winter moths typically emerge from the ground from late November to January, leaving the pupal state to mate and lay eggs. The moths seen flying around are male. The females have vestigial wings and are flightless, so they crawl up tree trunks and lay their eggs in crevices in the bark. They prefer oak trees, but also will infest maple, cherry, apple and aspen trees and blueberry bushes.

The moths die soon afterward. The eggs can survive the harshest winter weather. Defoliation follows the next spring, when the green, hairless caterpillars hatch from the eggs and feast on leaves before dropping to the ground to begin the pupal stage and form cocoons.

Aerial surveys conducted by the forest service have mapped moderate to heavy defoliation in the Cumberland County towns of Cape Elizabeth, Scarborough and Harpswell, as well as Chebeague Island and Peaks Island in Casco Bay, the forest service reported. On the ground, light to heavy defoliation has been seen in scattered locations from Kittery to Bar Harbor, from York County to Hancock County.

Heavy defoliation for several consecutive years leads to branch dieback and tree mortality, threatening an $8 billion forest industry that employs 38,789 Mainers, according to the forest service.

BATTLING THE BUGS – WITH BUGS

The forest service is taking steps to control and reduce winter moth infestations, and there are things that homeowners and others can do to help.

Funded by the federal government, the forest service has released parasitic flies in several locations in recent years, hoping to repeat successful moth population reductions achieved in Nova Scotia, said Teerling, the state forest entomologist.

Thousands of flies were released in Cape Elizabeth and Harpswell in 2013, Kittery Point, Harpswell and Vinalhaven in 2014, and Cape Elizabeth and Peaks Island in 2015.

“It’s going to be a while before we see any results,” Teerling said.

The service also has asked the public to report moth sightings through an online survey that drew more than 700 reports last year. Portland officials are seeing a spike this year in reports from residents on Peaks, Cliff, Great Diamond and Little Diamond islands, said Jeff Tarling, city arborist.

And the service set up more than 70 pheromone traps from Kittery to Bar Harbor, using the chemical excreted by female moths to capture and count male moths. Thousands have been trapped in Cape Elizabeth, Harpswell, South Portland and Kittery.

A pheromone trap is set up again this year at Scarborough Town Hall, said Town Manager Tom Hall. Thirteen moths were caught in the winter of 2013-14 and none were caught in 2014-15, according to forest service reports.

MOTH STRATEGIES FOR HOMEOWNERS

For homeowners concerned about protecting trees in their yards, Teerling said there’s likely little to worry about if you’ve only seen a few moths in recent weeks. If you’ve seen a lot of moths, there are some things you can do to stave off defoliation next spring.

One option is to spray a mineral-based horticultural oil, available at garden centers, on trunks and branches in late winter or very early spring, before leaves begin to bud, Teerling said. The oil smothers the caterpillars.

Bacteria-based pesticides also may be used to kill the caterpillars, although they may harm other moths, butterflies and bees, according to the University of Massachusetts Center for Agriculture, Food and the Environment. In the fall, some people wrap tree trunks in sticky bands, also sold at garden centers, that trap the female moths as they climb.

One of the best things that people can do to prevent the spread of winter moths is to avoid moving landscaping material – dirt, perennials, shrubs – from an affected area. Soil in a yard where a tree has been affected by winter moths will likely contain the insect in the pupal stage.

This warning would apply to homeowners who move from one neighborhood or town to another and to gardeners who like to swap plants with friends or sell them at yard sales or fundraisers.

“If you’ve got winter moths, you don’t want to share your plants with anyone,” Teerling said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.