CLARK COVE, WALPOLE — One farmer wore waders, the other was holding hundreds of 5-week-old seedlings in one hand. Their “tractor” was afloat. It was November and planting season at Maine Fresh Sea Farms was in full swing, in spite of a dungeon of fog that made the farm, a football-field-sized area of the Damariscotta River estuary, hard to see.

Seth Barker drove the boat while Sarah Redmond did the planting, which in the case of seaweed farming looks akin to casting on in knitting. That is, if instead of needles one used a thick hank of marine rope strung horizontally between moorings and substituted a 200-foot-long spool of twine covered with tiny bits of seaweed for a skein of yarn. As Barker chugged slowly through the water, Redmond played the twine out, twisting it around the marine rope.

Planting was over in less than 10 minutes, and the new crop, alaria escultenta, or “winged kelp,” was ready to flourish in the cold water. Next to it were ropes of sugar kelp and dulse in various stages of development.

The methods are not brand new, but three things made this crop of special interest. The seedlings had been certified organic by MOFGA, the Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners Association. They were of an edible variety still in the experimental stages of cultivation. Maine Fresh Sea Farms, which is funded by grants from NOAA (the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) and the USDA, is trying to extend growing seasons to harvest crops year-round, or at least nine months of the year. Winged kelp, like most seaweeds, is a winter crop, gathering nutrients from cool ocean waters when the micro algae of spring and summer have cleared out and the light can reach them. As every ambitious farmer knows, being able to deliver crops consistently throughout the year is a key component of building a business, and Maine Fresh Sea Farms wants to sell not just the more traditionally packaged dry seaweed, but fresh.

Redmond, who collaborates with Maine Fresh Sea Farms but works as an extension agent with Maine Sea Grant, began dreaming of being a seaweed farmer at age 15, shortly after the Maine Seaweed Council was formed. Now based at the University of Maine’s Center for Cooperative Aquaculture Research, Redmond is well aware that there are big questions about how well seaweed can be mainstreamed. (Just last month, The New Yorker published an article about seaweed cultivation headlined “A New Leaf,” with the subhead “Seaweed could be a miracle food – if we can figure out how to make it taste good.”)

Still, Redmond is seriously optimistic. She leaned backed on the gunwale and began listing off the crops Maine is famous for, potatoes and blueberries being the most obvious. Then she made a promise.

“We’re going to be known for kelp pretty soon,” she said.

FROM THE DEEP

Mainers have been harvesting both red and brown seaweeds – the latter the kind that tend to make small children squeamish about going in the water – for more than a century. Ten Maine seaweeds are harvested or cultivated commercially. All are edible and nutritious, although some more than others have been favored as food. These seaweeds, or “sea greens” as the branding experts would them known, have been used for everything from fertilizing gardens to animal feed to perhaps most consistently, in a financial sense, as a thickening agent for foods like puddings and ice creams. Irish moss, a red algae that yields carrageenan when processed, was driving the economy in Rockland back in the post-World War II years. (It remains an important part of Rockland’s economy, but the company that processes it uses imported seaweeds now.)

That’s the wild stuff. Seaweed has also been successfully cultivated, or farmed, worldwide for years; in 2013, after years of research, the Portland-based company Ocean Approved released a manual on how to grow kelp from spores. Redmond helped develop that manual, which is oriented toward New England waters.

Maine Fresh Sea Farms uses that manual, but they’re already going beyond it.

Those alaria seedlings Barker and Redmond planted were organically produced in the nursery – Redmond grew them naturally in filtered sea water in a tank at her lab in Franklin, but without feeding them the typical synthetic nutrients. (Barker uses fertilizers like fish emulsions for what he has been growing at the Darling Marine Center and because Maine Fresh Sea Farms is not certified organic yet, the final crop won’t be organic.) Kate Newkirk, the assistant director for processing and handling for MOFGA’s organic certification process, laughs when she’s asked if it was a challenge to determine how to determine what organic seaweed farming constitutes. She had to get up to speed on a whole new kind of farm. “Oh yeah,” she said. “It took a lot.”

Ultimately, the criteria focus on the ecosystem. An organic seaweed farmer shouldn’t disrupt natural beds or overtax the ecosystem, Newkirk said. Nor can they farm near fish farms because antibiotics are often fed to those fish. Any processing must be contaminant free. But perhaps the most important component of organic certification is what farmers do to protect the natural resource.

There’s a frontier feeling to this whole enterprise. Seaweed management is itself new; Maine’s Department of Marine Resources is in the process of developing its first plan, focused on management of rockweed, which is not generally eaten but represents more than 95 percent of seaweed landings in Maine.

Simply put, no one wants to deplete seaweeds. These plants protect shorelines, house and feed wild species and are being shown to improve human health. They can even perform what Peter Arnold, one of the founders of Maine Fresh Sea Farms, calls “environmental services.” In one study, seaweed planted right outside a sewage outfall not only thrived, but tested fit for animal feed.

“The indication is the plants don’t pick up the nasty stuff,” Arnold said. “They pick up the nutrients.”

ON THE ROAD

When Arnold called to talk, he was on his way to snowbird it in New Mexico. While his seaweed crop grows in Clark Cove, he’ll be working to expand the market for consumers. He had a 10-pound bag full of kelp (“like the biggest garbage bag you can imagine”) in the back of the car and planned to cut it into “noodles” and other shapes that might work for the home cook.

Arnold’s first job was harvesting Irish moss on the Maine coast in 1964. Later he went into the Peace Corps and landed in Chile, where he worked in marine algae development. After he retired from Chewonki, where he was the sustainability director, he and Barker and their third partner, Peter Fischer, who holds their acquaculture lease and started what is now the Pemaquid Mussel Farm, started talking about seaweed as a business.

The two NOAA grants Maine Fresh Sea Farms have won include Small Business Innovation Research grants to explore markets for locally grown seaweed. “They (NOAA) are thinking about, ‘How do you feed the world?'” Arnold said. “The land is pretty tapped out.”

“NOAA has chosen us to be at the vanguard of sea vegetables,” he said. “It is both a real honor and also very serious, because it is so important. Ocean farming is going to be a really big deal.”

The grants they’ve received have given Maine Fresh Sea Farms time to test markets. They’re considering ways to freeze and dry their product and sell it wholesale, like a mid-sized farmer. Demand is growing along with awareness – the Maine Seaweed Festival is already planning its third annual event in South Portland – but it’s not exactly a mainstay.

It’s Arnold’s task to figure out whether consumers will care about the organic component. And to persuade Maine restaurants and food producers to think of seaweed the way they think of land-based greens. Or spices and salt. Not that long ago, he showed up at Head Tide, a seasonal bakery in Damariscotta, pouches of seaweed in hand. He presented them to baker Anna Jansen and asked her if she could experiment. She tried adding the chopped-up dried kelp to her sourdough. “I really hit it big when I started making rolls,” Jansen said. “You get a depth of flavor. It’s richer.”

Chef Andrew Taylor of Hugo’s and Eventide in Portland uses dried sugar kelp as the base for stocks and chowders at both restaurants. He’s looking forward to playing with the fresh seaweeds when the harvest comes in, maybe pickling some of it. “We’ll probably make purees out of the dulse,” he said. He thinks his customers are plenty ready for it. “People have gotten used to it over the last decade or,” he said.

But he needs consistency. “They don’t really have much product right now,” he said. If Maine Fresh Sea Farms’ plan to increase their harvest from 2,000 pounds to 20,000 this year succeeds, Taylor should get that. He’ll also get more variety, including some even the most innovative chef might not have heard of.

Like “skinny kelp,” a longer and thinner form of sugar kelp. Redmond will seed it this month. “It tastes different,” she said. “But it is really good. Very mild, good consistency.” (As you might guess, she does not hold with The New Yorker’s opinion of seaweed as food.) It should be ready to harvest in May, and like so many local foods, has a level of intrigue that should prove useful in marketing; its parent plants can only be found on ledges in Harpswell.

FOSTERING GROWTH

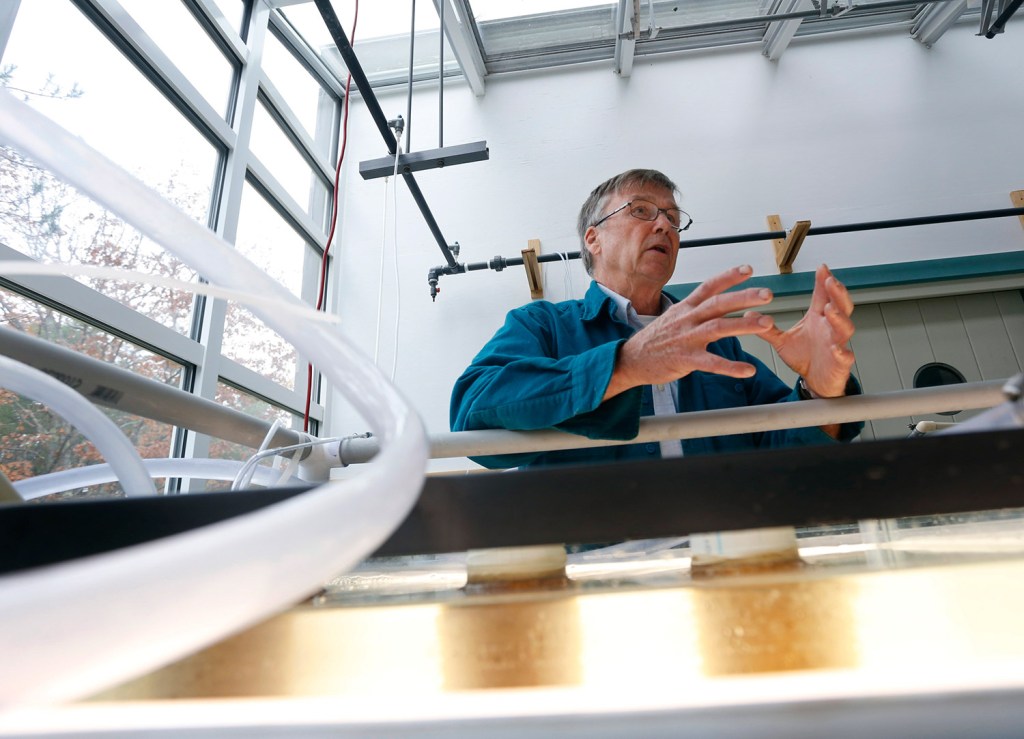

“Welcome to the nursery,” Barker says, opening the door onto a room at the Darling Marine Center’s Aquaculture Business Incubator in Walpole. Light streams through the walls of windows and into a few mid-sized tanks in the middle of the room. Sitting in each are pieces of PVC pipe wrapped with twine and tiny seedlings, the same kind of arrangement Redmond had used out in the fields. Maine Fresh Sea Farms set up the nursery in July and by September had their first five-week old kelp seedlings ready to plant. A second crop was in the water by October. The third round of seedlings were already in good shape to plant although to the uneducated eye, they looked mostly like an amber fuzz on the twine.

Maine Fresh Sea Farms will turn two in January, but they’d tested the waters for a few years before that. There have been some wins and some misses. Redmond successfully grew laminaria digitata (horsetail kelp) in a tank, but it didn’t take well at the Clark Cove location. Arnold theorizes that it needed faster currents to thrive. Since horsetail kelp is in high demand, Maine Fresh Sea Farms will seek out other places to plant it.

Barker is a longtime marine biologist who worked for the Department of Marine Resources for 29 years. Like Arnold, he’s come full circle. His very first job in Maine was in the 1970s at Darling, where he did environmental research on Maine Yankee’s impacts. In the 1980s he grew rope-cultured mussels with Ed Meyers, Maine’s original mussel farmer, in Clark Cove.

Unlike Redmond, Barker is not a big consumer of seaweed, a fact he shares predicated by a bashful, “I’ll be honest…” He’s more of a beginner, sprinkling dried dulse (a red algae said to have a bacon like flavor) on popcorn or pizza. But he sees the potential, especially now that he has access to fresh farm-raised product. “You can take a taco and shred some seaweed on it.”

Like cabbage. Like radishes. Or anything else at the farmers market. This farm has bigger dreams for aquaculture in the middle – not too big and commercial, not too small to make money, but Barker would still like to pass one traditional signpost of a farmer’s worth.

“When we can go to a farmers market and see sea kelp for sale, then we’ll know we are there,” he said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.