EAST MACHIAS — The building once defied salmon, sheltering the turbines of a dam that long hindered the fish from proceeding up the East Machias River.

Now it’s being used to power an effort to restore the endangered, failing fish to this Washington County river – an effort that, if successful, carries the promise of heading off the extinction of U.S. salmon populations and the sport angling they once supported.

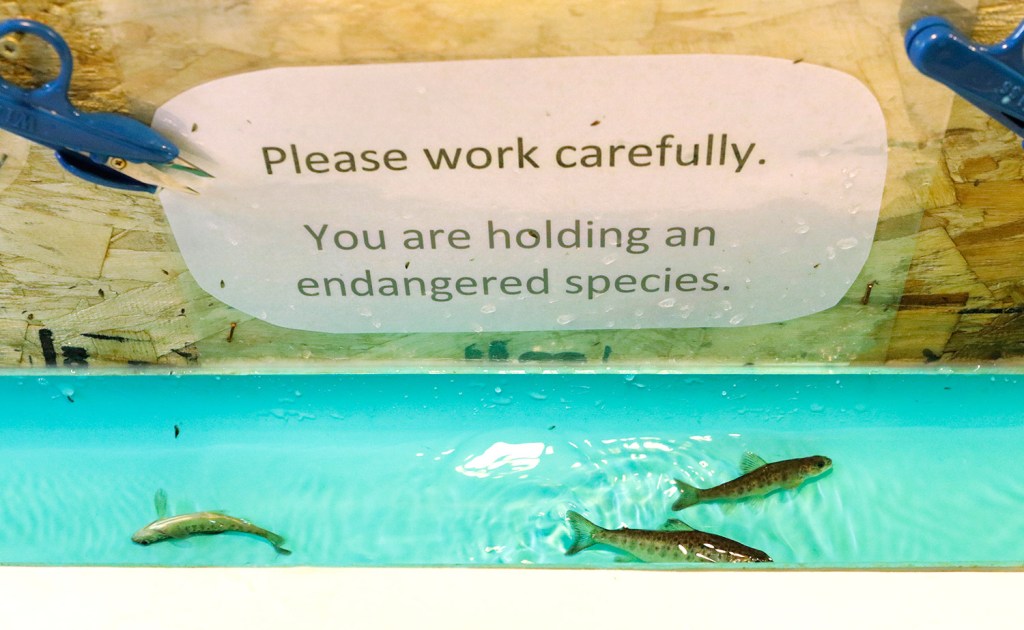

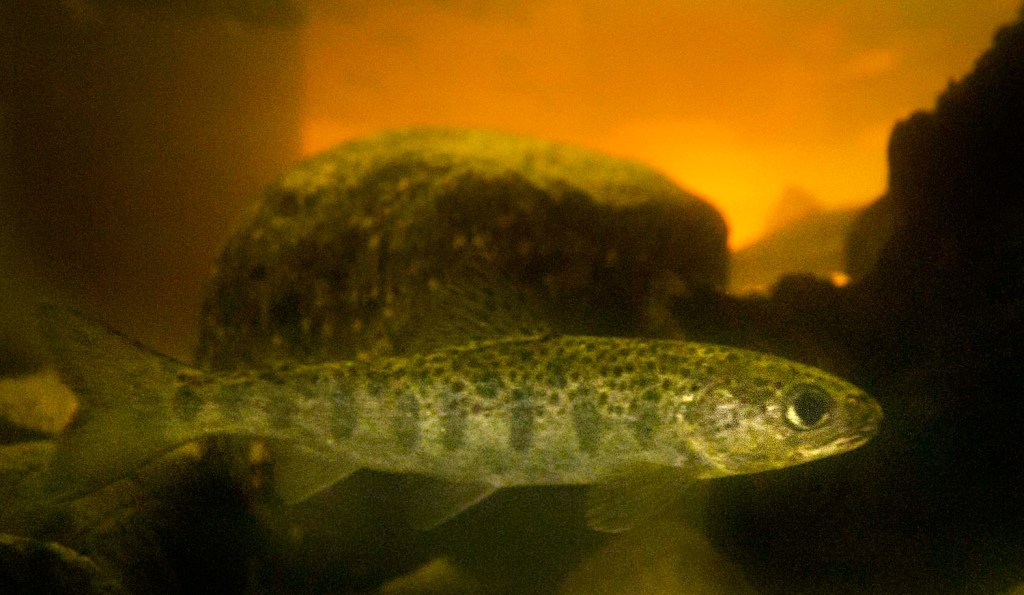

Early this summer 300,000 baby salmon swam in the special growing tanks inside the once-derelict building, now a hatchery engaged in an innovative project that aims to jump-start the recolonization of the river. This month the hatchery’s fish, each 4 to 5 inches long and carrying the genetic inheritance of this very river, were released in locations throughout the watershed, as they have for four years running.

“We’re taking dam removals and river restoration to the next logical step, which is to work with the fish themselves,” says Dwayne Shaw, executive director of the Downeast Salmon Federation, which owns and operates the hatchery. “It’s one thing to take the dam out, but then to take the blighted sites in the middle of these villages and turn them into research centers and hatcheries made sense.”

Supported by Icelandic funding, Scottish experience and know-how, and local initiative, the East Machias project aims to rescue an iconic fish that has lately seemed destined to be extinguished from Maine in the face of past pollution and dam building, present-day overfishing in Greenland, and the ongoing warming of the climate in New England, which is at the southernmost part of their range. The Greenland fishing issue has become so contentious in the rarefied world of fisheries diplomacy, it may endanger Icelandic funding of the Maine project.

“We have to try different approaches, because clearly conventional stocking doesn’t seem to be working on the Down East rivers,” says Andrew Goode, vice president for U.S. programs at the Atlantic Salmon Federation, an international conservation group based in Chamcook, New Brunswick. “We’re cautiously optimistic about its success.”

The approach, which turned a blighted river on the Scotland-England border into one of the greatest salmon angling locations in the British Isles, focuses on growing fitter fish. Pioneered over four decades by the late Peter Gray, the Scottish manager of a hatchery on the River Tyne, it hatches and raises baby fish in on-river hatcheries using local, unfiltered water and a variety of techniques that more closely mimic the natural environment of early life-stage salmon.

Gray, who visited East Machias multiple times before his death two years ago, showed that his fish – “young athletes,” he called them – could succeed where conventional stocking efforts had not. Salmon rod catches on the River Tyne, which had fallen to just 70 fish in 1965, now exceed 5,000, even as the overall population has hit record levels: more than 40,000 this year, according to the United Kingdom Environment Agency.

RESTORATION EFFORTS HIT HEADWINDS

Meanwhile, wild Atlantic salmon populations in the United States – almost entirely found in Maine – have plummeted, with the fish listed as an endangered species in 2000. Federal scientists had discovered that each Maine river had a genetically distinct population evolved to spawn and survive in its particular conditions. Under the rescue plan they developed, brood stocks from each of eight river systems are maintained at the federal hatcheries in East Orland, producing the eggs and fry that are supposed to recolonize their respective rivers.

Despite the stocking, removal of dams and ongoing efforts to improve habitat, the salmon have not rebounded.

Atlantic salmon typically spend their first two years in their native rivers, then two years out in the ocean, with those in Maine traveling to Greenland, Labrador and the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Last year the number returning to their native rivers hit the lowest level on record: just 450 in the United States, two-thirds of them in the Penobscot River, according to the Atlantic Salmon Federation. In the Saint John River, which starts in northern Maine and ends in the New Brunswick city of the same name, returns were also at historic lows last year, and fish counts in the more northerly and pristine Miramichi saw steep declines.

Nobody knows exactly why, but suspects include rising water temperatures – which broke historic records in the Gulf of Maine in 2013 – and the reopening of commercial salmon fishing and fish processing in Greenland, a move sternly opposed by much of the salmon conservation community.

Federal and state authorities have tried all sorts of approaches to boost the number of fish in Maine’s rivers: carefully planting salmon eggs in riverbeds; stocking adult, egg-bearing females near likely spawning habitat; stocking hatchery-raised fry, parr or smolts, life stages roughly analogous to human toddlers, school kids and teenagers. The efforts often succeed in their immediate aims of boosting a fresh cohort of a certain stage of fish, but in the broader picture salmon populations are failing to recover.

“The hope is that through restoration and habitat improvement you can transition away from reliance on conservation hatcheries,” says Peter Lamothe, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s manager of the hatchery operations in Maine. “We’re not at the point where we could rely on the rivers to maintain these populations.”

AN INTERNATIONAL PARTNERSHIP

This is where the East Machias hatchery comes in.

The Downeast Salmon Federation purchased an abandoned building a decade ago and in 2011 completed a $1.25 million renovation to create the East Machias Aquatic Research Center, an on-river hatchery, research facility and community center modeled on its headquarters in another former dam building in Columbia Falls, on the Pleasant River.

“The focus is on fish, but there’s so much more to it,” says Kyle Winslow, the hatchery’s supervisor. “We host movie nights, art displays and school groups, and even run an alewife smoking operation.” Each year local college and public school students help mark thousands of juvenile fish before they’re released.

Just as the hatchery was completed, the federation was approached by the North Atlantic Salmon Fund, a conservation organization based in Reykjavik, Iceland, that had been looking for just such a location to try to repeat Peter Gray’s successes in the River Tyne in North America.

“I sent my experts to visit some areas and hatcheries and he came back to me and said, ‘Orri, I think this is it. I think this is our best bet,’ ” recalls the North Atlantic Salmon Fund’s founder and chairman, Orri Vigfusson.

The result: The fund agreed to underwrite the lion’s share of the cost of the initial five-year project, whereby hundreds of thousands of native East Machias strain eggs hatched at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s East Orland facility are grown on-site using Gray’s methodology. A key element: The fish are born and raised in water pumped directly from the adjacent river, with all the natural temperature, mineralogical, food supply and pathogenic conditions, presumably resulting in a hardier, more fit fish.

Instead of keeping fresh hatchlings in large tanks, they live in incubation boxes that mimic their natural nests: a thick layer of gravel they can hide out within. When their egg sacs are used up, they swim out and enter larger tanks.

Many hatcheries use clear grow tanks, but here they are black because the baby fish take on the color of their surroundings. “In a clear tank, they start to turn blue, and when you first put them in the river they’re kind of a glowing sign against the background” – an easy mark for predators, Winslow notes, gesturing to a tank filled with more than 30,000 fry. Throughout, water flow conditions are geared to mimic natural conditions.

Instead of releasing fry – which are just a few months old – Gray’s approach uses year-old parr and huge numbers of them. “You have a lot of vacant habitat in a river like the East Machias, and a lot of non-native fish like bass,” says the Atlantic Salmon Federation’s Goode. “How can you overrun the habitat and the predators with high stocking densities?”

SUCCESS UNKNOWN

It’s too early to tell whether the approach is working. This month, project staff released their fourth annual cohort of salmon parr – more than 300,000, in this case – and any fish from the first year wouldn’t be expected to return from the open ocean to spawn until next year.

Initial indicators of how many year-old parr are surviving to become 2- to 4-year-old smolts are mixed. Smolt numbers were up a year ago, but preliminary results from this year’s survey are discouraging.

“We went from around 1,000 or so to only 300 to 400, so something happened,” says Larry Atkinson, a Department of Marine Resources fisheries scientist who was involved in the survey. “It was a weird winter, but it also may be that we just put too many out.… There’s no clear pattern right now.”

It’s also unclear whether the North Atlantic Salmon Fund will continue supporting the project after 2016 because of the organization’s frustration with unrelated aspects of U.S. salmon conservation policies. Vigfusson says he is upset with what he sees as the State Department’s and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s failures to put adequate pressure on Greenland to close its commercial salmon harvest, which he says is putting restoration efforts at risk.

“I am now reviewing my participation in this project, because I think the USA is not living up to what it should do,” he says.

That said, it’s not a reflection on the East Machias project itself, which he thinks is the best chance for Atlantic salmon. “This is our best project, although one of my concerns is with rising temperatures,” he adds. ” If we fail here, I think the game is over for wild salmon in Maine.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.