M

unjoy Hill is like the lobster of Portland neighborhoods, explains Anne Rand, a 69-year-old lifelong resident of Portland’s easternmost neighborhood.

Like the crustaceans crawling around the floor of nearby Casco Bay, “the Hill” was once consigned to the poor who couldn’t afford anything better, and is now considered precious. Yet, in Rand’s view, little has changed besides the perception.

“I was always very proud to be from the Hill,” said Rand, who once also represented the community in the state Legislature.

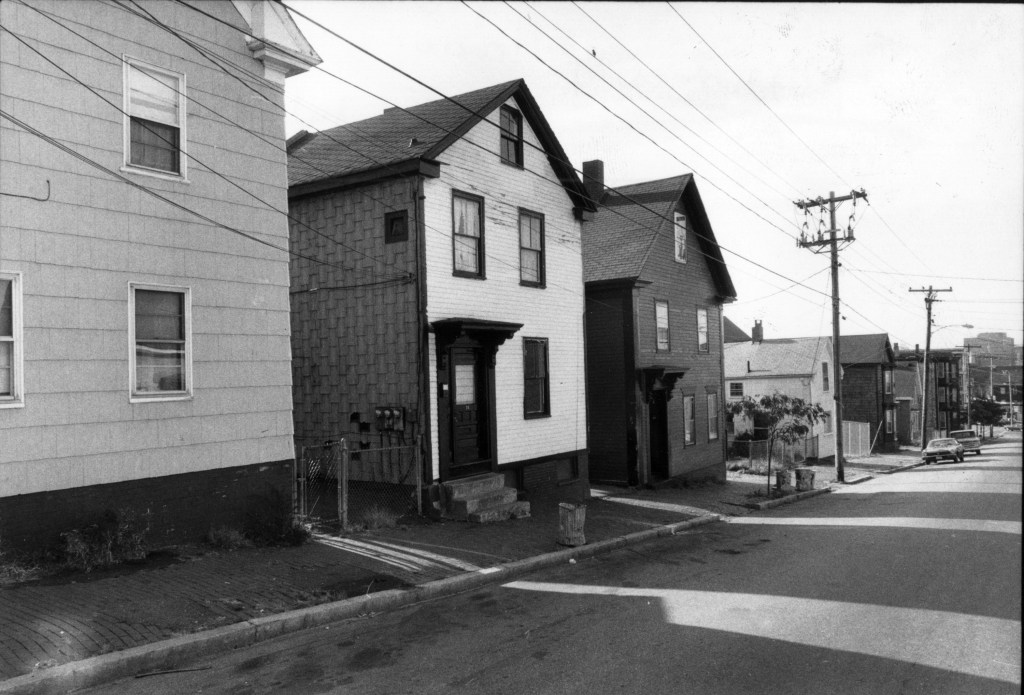

That change in perception over the past decade or two is now driving other shifts in one of Portland’s most historic and storied neighborhoods, where million-dollar condos are rising among the aging two- and three-story houses squeezed together along narrow side streets.

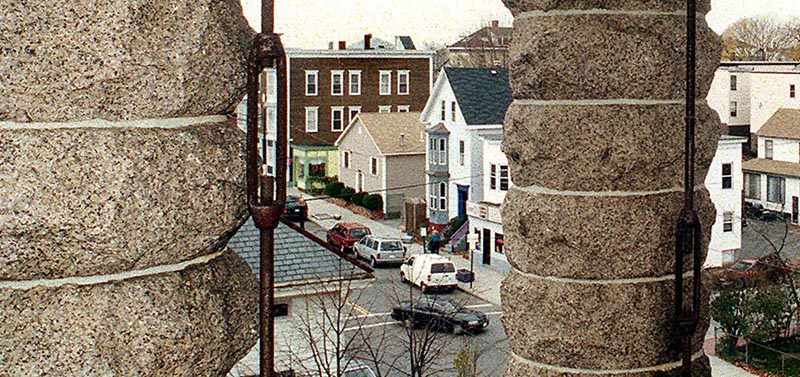

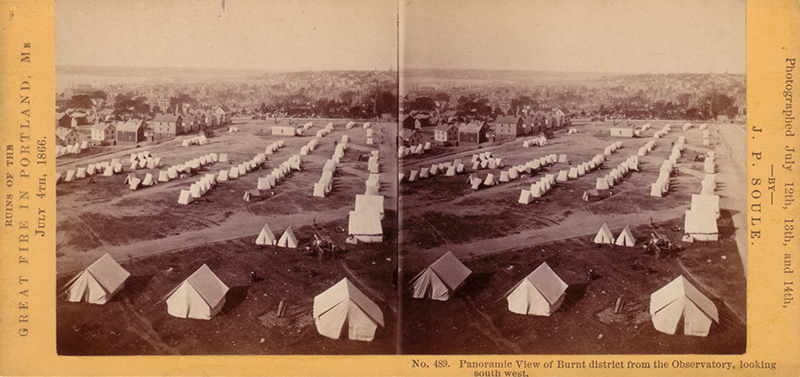

Bound to the west by Washington Avenue and Mountfort Street and on all other sides by Casco Bay, the coastal hill overlooking downtown Portland had built up as an enclave for immigrant workers and their families and in recent years has become the city’s most sought-after place to live. The increase in popularity has brought a fast and dramatic rise in rental costs and property values, leaving little breathing room in the packed-in neighborhood for the average Portland resident.

The gentrification of Munjoy Hill is evident in high-end produce markets and trendy restaurants that have replaced the corner stores of Rand’s childhood. It’s also evident in U.S. Census data showing some of Portland’s biggest increases in rental and sales prices, as well as demographic shifts. The Hill is now the city’s most educated neighborhood, with about two-thirds of residents holding bachelor’s degrees, compared with less than half of Portland’s population as a whole. In 1980, it was one of the less educated neighborhoods, with 13 percent to 17 percent holding bachelor’s degrees compared with 19 percent citywide.

And, once the home of the highest concentration of black residents in the city, it is now the least diverse neighborhood on the peninsula.

When Rand was a kid there, everyone on the Hill was either poor or lower middle-class, mostly from Italian, Irish or Jewish families, although they made no distinction between them.

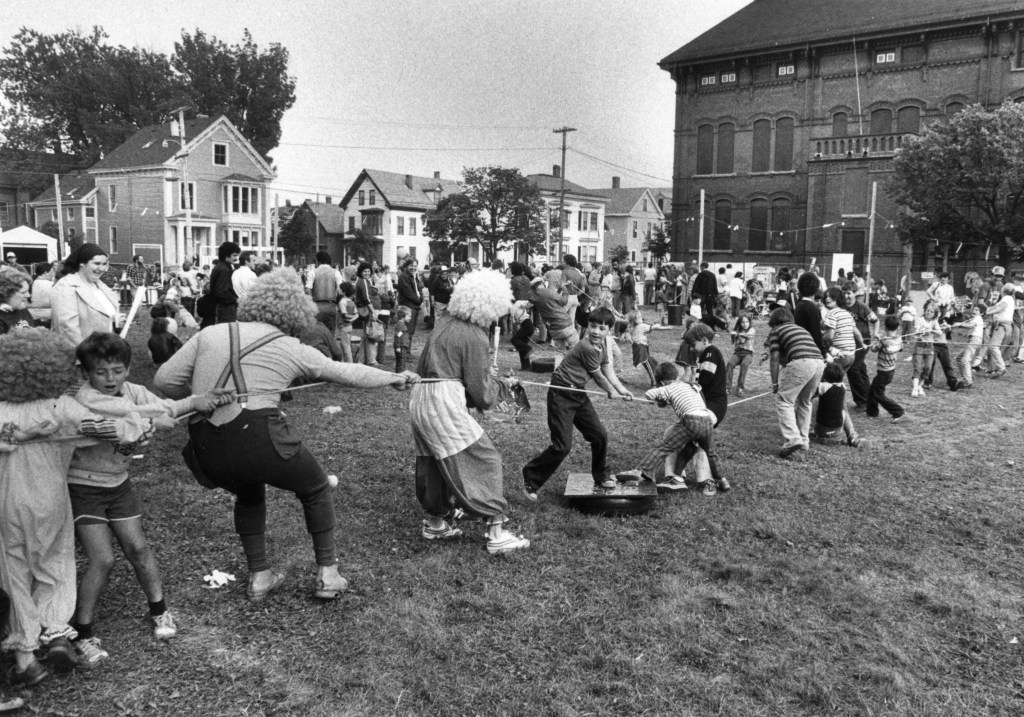

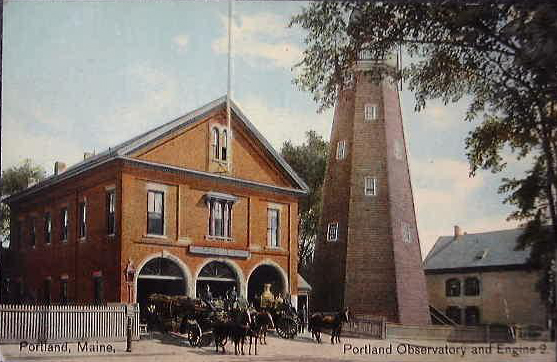

There were so many kids that no one needed to go far beyond their block to find friends to go ride bikes, walk on fences, jump in the ocean and play hide-and-seek until the 9 p.m. whistle blew from behind the fire barn. Later, she met her future husband in front of the store on the corner of her street.

But her children didn’t have the same experience.

At some point, owning a house with a lawn became the American Dream, and Rand watched as her neighbors moved off the peninsula. Large apartments where whole families once lived were broken up into smaller units, drawing a different demographic. Schools closed and the constant sound of children playing in the streets subsided.

In the 1970s and 1980s, the Hill had a reputation among outsiders as a place to avoid. Rand remembers buying the house she lives in now and telling someone at work, who cringed when she heard where it was. People were shocked that she walked there by herself at night. She didn’t understand.

“I thought I lived in heaven, and I did, and I never wanted to leave it, and I haven’t,” she said.

The past decade has been different. Now, when people hear where she lives, they gush about how much her house must be worth. She’s also noticed the kids have started to come back.

“It’s absolutely wonderful,” she said. “They’re out playing. They’re giggling and laughing.”

The turnaround in perception clearly caught the attention of developers and speculators. Recent construction includes knocked-down houses replaced with fancy new ones, luxury town homes with roof decks overlooking the city, and condominiums going for $750,000 and up.

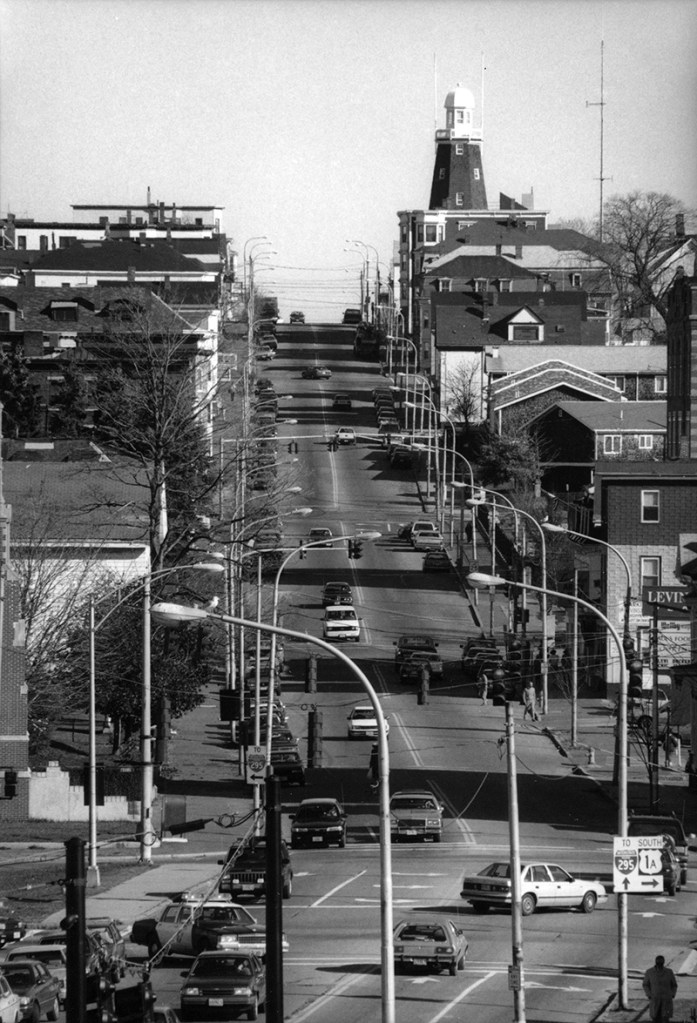

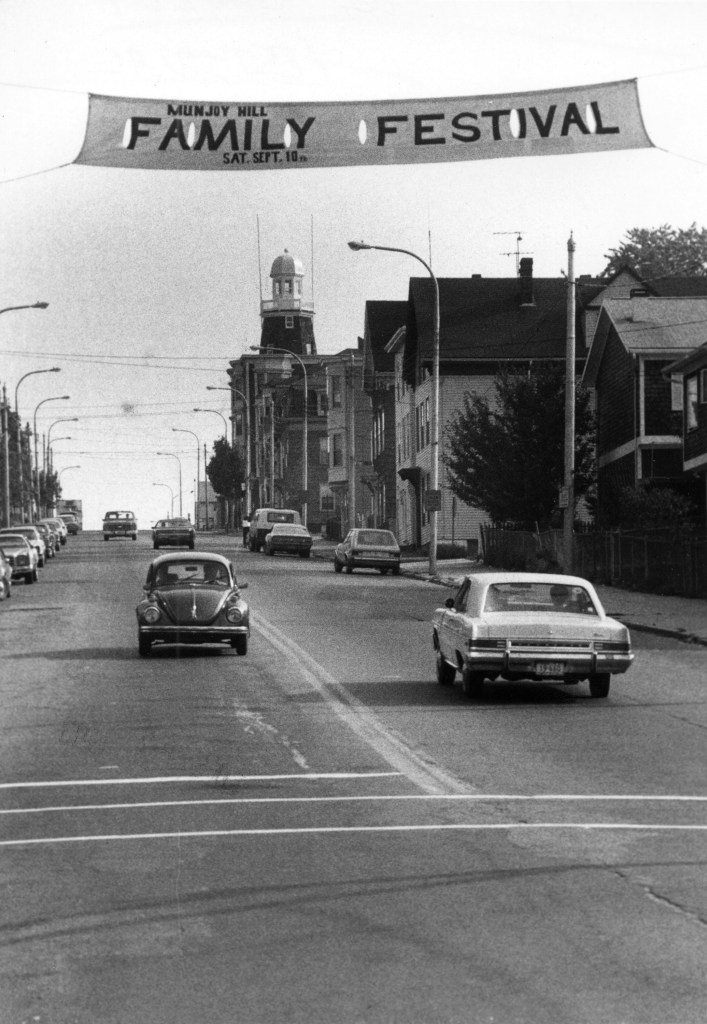

July 29, 2015, photo by Jill Brady/Staff Photographer; Jan. 25, 1990, Portland Evening Express photograph courtesy of Portland Portland Library Special Collections & Archives

Duncan Elder watched one high-priced condo project rising outside his bedroom window where there had been an empty parking lot when he moved in last year.

The 29-year-old chef was living in the finished attic of an apartment he shared with two roommates in a three-unit house. He said he feels lucky to have seen a post shared by a friend on Facebook seeking someone to move into the place. He paid $700 a month for his attic space – the limit of what he can afford, but pretty much the minimum price for a bedroom on the Hill for renters who don’t have incomes low enough to qualify for one of the neighborhood’s subsidized apartments.

Even $700 for one-third of an apartment is a lot compared with rents of the past. Elder lived in another apartment on Munjoy Hill about five years earlier and paid half as much. He also has noticed other changes.

“There were more Mainers. Now there’s more strangers,” said Elder, who grew up in Brunswick. Except for the fact that living there is harder to afford, the changes didn’t bother him.

“I think that it’s cool that the East End has become a desired place to live,” he said, noting that such a shift often translates into a cleaner, safer neighborhood. “Who wouldn’t want that?”

Although he patronized some of the new businesses in the area, such as Union Bagel Co. and the Portland Food Co-op, that have popped up since he last lived here, he was mostly drawn back to the neighborhood by the same things that had attracted him in the first place: the ocean breeze, the Eastern Promenade and the congenial community.

And, although different types of people populate Munjoy Hill now – immigrants from Africa and affluent newcomers from out of state now mix with native Portlanders – Rand believes there’s more about the neighborhood that’s stayed the same than changed.

“There’s a sense of community here, there still is,” she said. “We shovel each other’s driveways.”

Elder may have an explanation for why everyone’s so friendly.

“I think anybody who’s living on the Hill right now,” he said, “is just happy to be here.”

But Elder can no longer count himself among them. After learning that his housing costs were going up in September, he spent a couple months crashing on couches before finding an apartment he could afford — in Parkside.

Send questions/comments to the editors.