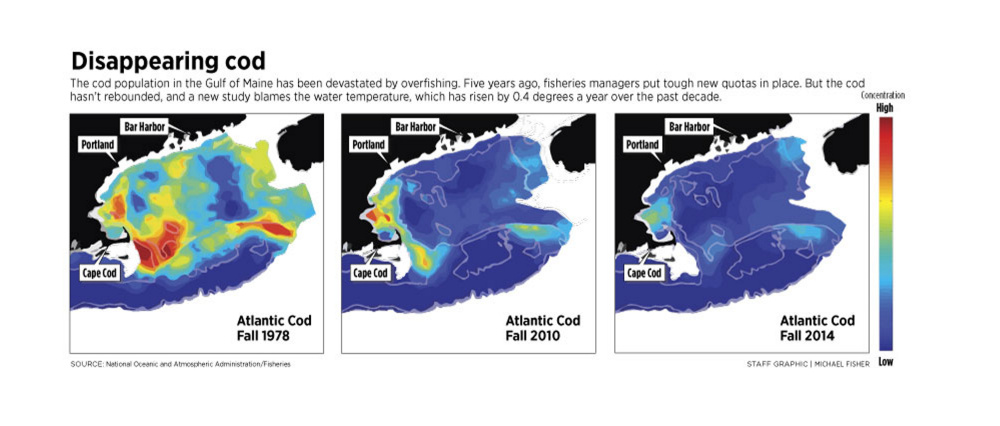

The rapid warming of the Gulf of Maine over the past decade is largely responsible for the surprising failure of the Gulf of Maine cod stocks to rebound from overfishing, according to a new study.

Five years ago, federal fisheries managers put tough fishing quotas in place to protect the region’s cod until their populations could rebuild from the devastating effects of decades of overfishing. To their surprise, the Gulf of Maine cod stock continued to decline, prompting a near-closure of the fishery. The size of the adult stock – an estimated 3,000 metric tons – is just 4 percent of what would be needed to support an optimal fishery.

The study by Andrew Pershing, chief science officer at the Gulf of Maine Research Institute, and 11 colleagues from that and three other research institutions found that warming-related stresses accounted for much of the discrepancy between what managers thought would happen to the stock and what actually occurred. The study was published Thursday in the journal Science.

“Managers kept reducing quotas, but the cod population kept declining,” Pershing said in a written statement. “It turns out the warming waters were making the Gulf of Maine less hospitable for cod, and the management response was too slow to keep up with the changes.”

The Gulf of Maine – which extends from Cape Cod in Massachusetts to Cape Sable at the southern tip of Nova Scotia, and includes the Bay of Fundy, the offshore fishing banks and the entire coast of Maine – has been warming rapidly as the deep-water currents that feed it have shifted. Since 2004, the gulf has warmed faster than anyplace else in the world’s oceans, except for an area northeast of Japan, and during the “Northwest Atlantic Ocean heat wave” of 2012, average water temperatures hit the highest level in the 150 years that humans have been recording them.

“You can see the influence of temperature on the cod stock in a variety of ways, including the failure of the young to survive as they get older and the loss of more older fish along the way,” said co-author Katherine Mills of GMRI. “When we’re looking at rapidly warming systems, we need to change the way we do things and incorporate these effects into stock assessments.”

The scientists from GMRI, the University of Maine, the Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences, Stony Brook University and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Earth System Research Laboratory recalculated population projections from the official federal stock assessments of the past 10 years, this time taking into account the deleterious effects of warmer water.

The result: Instead of predicting the growth in numbers that managers had expected, the projections indicated the stock would decline, which is in fact what happened out in the water. “They were overestimating the stock because the assessment models did not incorporate the temperature changes,” Mills noted.

The warmer temperatures increased the metabolic demands on the juvenile fish, she said, requiring that they find more food to grow and survive. Warmer waters also increased predation by extending the hunting season of spiny dogfish and other species that eat small cod.

Michael Fogarty, chief of the ecosystem assessment program at the National Fisheries Service’s Northeast Fisheries Science Center in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, says the study is an important contribution, and mirrors results of a study he and his colleagues published in 2008 that predicted warmer temperatures would harm cod stock recovery.

That 2008 study analyzed warming data through 2004, just before the record-breaking recent temperature spike began. “The results they got are quite similar to the ones we had before, but the temperature increased much faster than we thought it would, so the time frame was very different,” Fogarty said. “I can tell you nobody expected the kind of increase we saw in 2012 based on the measures we had” in 2007 and 2008, he said.

Over the past decade, average sea surface temperatures increased at the shocking rate of about 0.4 degrees Fahrenheit per year, dwarfing the 30-year warming trend of 0.054 degrees a year. Scientists do not expect that enhanced rate of warming to continue, but long-term projections for our region by Canadian government scientists predict a rate of 0.1 degree per year through 2065, which would make 2012-like temperatures the “new normal” by mid-century.

Send questions/comments to the editors.