Last fall I invited an energy auditor into my house. He admired its high ceilings, circa 1875, and sunny, south-facing exposure, but that was just the top layer of a very meaty criticism sandwich.

“I could put the blower in the door,” he said, referring to the main weapon in the energy auditor’s arsenal, a powerful fan that tests how airtight homes are (or are not) and when combined with infrared technology, helps reveals every leaky nook and cranny in the home’s envelope. “But just looking at it, I can tell you that you are losing about 50 percent of your heat.”

The attic was the most obvious place, but the cellar was highly suspect as well, and all the walls needed blown-in insulation, he said. These old houses, he went on, shaking his head, are like sieves. I began to wilt. It’s demoralizing to be told about invisible flaws; it feels like scolding. But I almost passed out when his written proposal to fix the problems arrived a couple of weeks later: $22,850, minus the $1,500 rebate I’d get through Efficiency Maine for being a dutiful weatherizer. If I did all this, the proposal said, the projected reduction in my heating load would be 55 percent, and I’d be paid back (in savings) in 8.3 years.

I did nothing.

I’ve been thinking about the reasons. I love my house and am quite comfortable there, even with the thermostat never going above 62 degrees. It’s cool in the summer and cozy in the winter. Being told it essentially sucks (in the cold) and blows (out the warm) wasn’t fun.

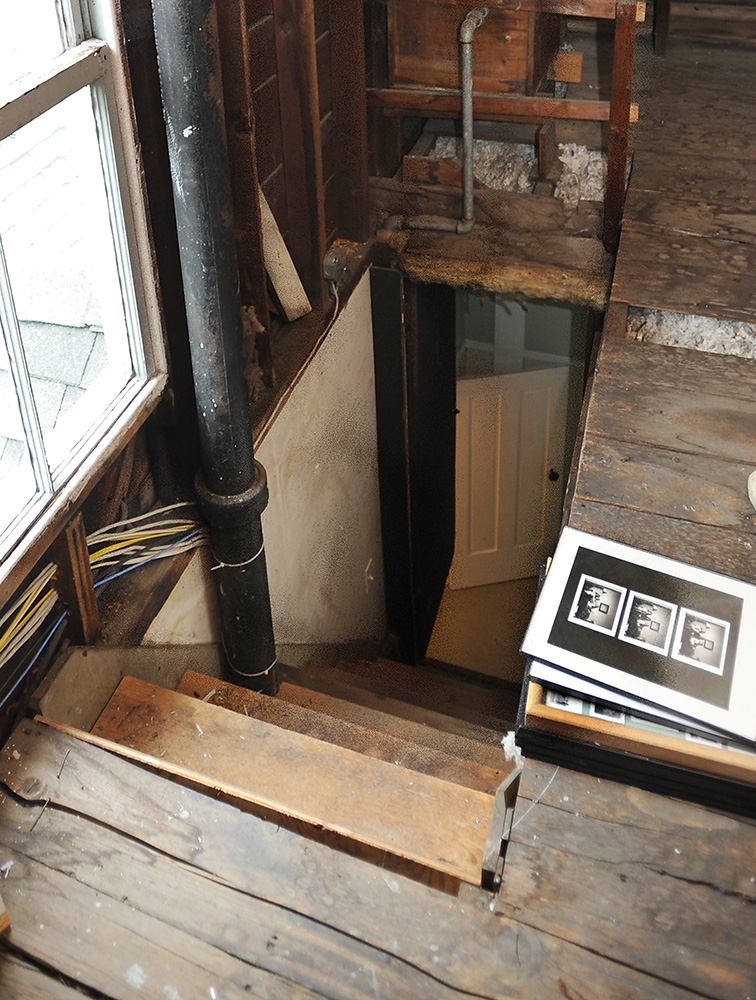

Moreover, I don’t have that kind of money – we’re talking $4,710 just for the cellar work – and if I did, using it for a kitchen remodel would feel much more delicious and life-altering than spraying insulating foam all over the walls of a cellar that, quite frankly, is already only suitable for shooting horror films and/or exercising the cat (there are mice).

However, weatherizing is not meant to be delicious. Weatherizing is one of those sensible, practical things that we do so that we can save money on heating costs and, if we’re sustainably inclined, feel better about our carbon footprint. It should be a Yankee’s dream task.

Except that most Yankees harbor the quiet suspicion that they’re being ripped off and a $22,850 price tag for something that you don’t entirely understand (“kraft-faced insulation” – is that, like, a cheese?) and in most cases, won’t see, would be enough to make even Pope Francis suspicious. Especially after I ran into a friend who used the same company, is still paying her loan off and feels as though her house is cold and her heating costs haven’t dropped radically. But another friend had raved about this company. Confusing, right?

Many, many people, when confronted with a confusing option and the status quo will pick the status quo. My status quo has been coming up with the money for approximately 1,200 gallons of No. 2 fuel oil in an average winter, plus 230 gallons of propane for the supplemental gas stove to warm the chilly kitchen.

To keep the house at 62 degrees. My status quo is appalling. I needed to take action.

The first action had to be clearing up some of the confusion.

I sought second, third and fourth opinions on what I should do, including visiting Efficiency Maine itself to talk through both the global issue of weatherization and a few specifics about my own home with Executive Director Michael Stoddard and Dana Fischer, the nonprofit’s residential program manager.

This experience felt a bit like being in an episode of “What Not to Wear” except it was my house that was getting the makeover, and mostly I was being told What it Should Wear (cellulose, rigid foam, spray foam, and so forth). Unsurprisingly, this is the busiest time of the year for weatherizing, but Stoddard and Fischer assured me it’s never too late to get started.

I told everyone I talked to that I was working with a budget of between $5,000 and $6,000 and wanted to do the best I could with that money. Here are the eight most important and useful things I learned, all of which can apply to your homes as well.

DON’T SKIP THE BLOWER DOOR TEST

Fischer kindly pulled out a blower door and explained how it works, sucking air out of the house – so powerfully that one blower door works on even a big house (mine is 3,200 square feet) – and lowering the air pressure inside. That pushes the air from outside into all the places where air is usually moving in and out of the house without us noticing, and a camera that spots heat shifts can track exactly where the leaks are.

My guy skipped the blower door test, which means he didn’t do a true energy audit of my home. He didn’t charge me anything, so it’s not like he cheated me. But without that, I wouldn’t be eligible for any of the rebates Efficiency Maine offers for weatherization. The blower door test, when done in conjunction with at least six hours of air sealing by a contractor on Efficiency Maine’s “approved” list, gets you a $400 rebate. The cap for Efficiency Maine rebates is $1,500 per home (not per year, which for a brief while was my happy misconception), so keep in mind, that leaves you with $1,100 more potential savings in rebates.

My guy didn’t have to work hard in assessing my house as losing 50 percent of its heat through leaks, because that’s the average in Maine. Ouch. We don’t measure up well, unless it’s in a contest for most-Swiss-cheese-like-housing-stock. Efficiency Maine just did a residential baseline study and concluded that Maine, which has about 500,000 homes, has the leakiest housing stock in the New England region. That’s partly because we have older homes and partly because some Maine homes were originally built as camps and cottages. Maybe they’ve been converted to year-round use, but that’s not the same as being built to provide shelter 365 days a year in the first place. Also, we’re further north and our homes take a beating from wind and weather. “They’re doing hard duty,” said Stoddard, Efficiency Maine’s executive director. The rankings are complicated – the number reflects how many times in an hour, under a pressure test, the air in a home will go through a complete exchange with outdoor air – but on a scale on which Vermont homes average a 7.8 in terms of heat loss, Maine is at 11.2.

“A 7 is OK,” Stoddard said. “A 3 is awesome.” Anything above a 7 is “just wasting energy.”

“Our goal is to get everyone to a 7 by 2030,” he said. Which would save $200 million in energy costs a year just in Maine. You could see why Efficiency Maine would be pushing weatherization.

QUESTION YOUR HEATING SYSTEM

When I got my estimate for weatherizing, I was dealing with a cracked and dying oil furnace – and fuming because it was only eight years old – and considering replacement systems. I had a fantasy about renewable energies like a geothermal system, which would have cost me nearly a year’s salary but get me off the fossil fuel teat. I also sought an estimate for heat pumps, which are becoming vastly popular. Since July 1, Mainers have installed 1,200 heat pumps, which transfer thermal energy and work on the same model as refrigeration systems, except instead of sending heat outside, they bring it inside.

Efficiency Maine is thrilled about that. (Even the governor has a few in Blaine House.) But Stoddard and Fischer both expressed concern that some Mainers are not getting the maximum benefit from the heat pumps that they should or could. That Yankee parsimony tends to keep people from turning the thermostat on the pumps high enough. Sometimes they even turn the heat pumps off altogether. Even if a heat pump is being used as a supplemental or secondary heating source, it should lead the overall system.

“You need to turn it up as much as you need to make yourself comfortable,” Fischer said. “This makes people nervous because they think they are going to get a huge electric bill.”

Case in point: Fischer kept his heat pump’s thermostat at 78 throughout February in order to achieve an overall temperature of 68 degrees in his 1820s Cape. His electric bill for that brutally cold month was only $100 higher than usual.

“It really is exciting what this technology offers our state,” Stoddard said,

But on the advice of everyone who saw my gloriously ornate and huge radiators – one as long and about as heavy as a piano – I decided to stick with my forced hot water system but switch to a high-efficiency propane boiler, which makes that 62 degrees extend farther without burning more fuel.

START AT THE TOP, WITH THE ATTIC

Did your mother shriek at you when you went out without a hat? (In my house, it was my father and he growled it.) Indisputable fact: heat rises. And if you’ve got a lot of holes in your thermal envelope, that heat is going to exit the attic.

Everyone I consulted said that I should start in my attic.

My proposal called for $3,275 worth of work in the “primary” attic, i.e., non-crawl space. I’ve got an attic you can stand up in, and I’ve even dabbled with the thought of finishing it someday (like maybe 2030). But I also have “attics” above the dining room ($1,125 for that) and the sunroom side of the kitchen ($875) as well as the ell attic ($1,605). That’s a grand total of $6,880. I could blow my whole budget on the attic and be done, although Efficiency Maine wouldn’t jump for joy over this approach (see below). But I could also try to get that number down in various ways, including doing some of the work myself. Some rolls of insulation, a staple gun, some foam insulation and using the leak locations identified by the blower test.

“A flat attic might cost you $700 to do,” said Brunswick energy auditor DeWitt Kimball, “where if you go to a good company, it will cost you $3,500. It’s not because they are ripping you off, but they have got insurance and workers to pay for and so on.”

But, as he observed, “most attics are disgusting,” which explains why most people don’t opt for this route. Kimball wishes Efficiency Maine would add a provision to let DIY residents get rebates too; that would be motivating.

GET MULTIPLE BIDS

Stoddard pointed out that even experienced homeowners who might be on their second or third such project tend to do the default: ask a friend for a recommendation of someone they used that they liked, get a bid from that person and if they seem like a decent person (my guy was smart, charming and easy to talk to) proceed with the work. We’re all busy and this takes the least amount of time, but it truly doesn’t make the most sense.

“What we have found is if you find two or three people to give you a bid, the prices will come down,” Stoddard said.

There are a lot of contractors on the Efficiency Maine website, and they’ve all filed the basic paperwork to get there, including signing a contract agreeing to working within the group’s standards. But maybe you know and trust someone and believe they can give you a better price that in the end will save you as much as the $1,500 rebate.

Or maybe you are not comfortable with the Efficiency Maine route because it steers you toward working with the person who points out your problems and benefits from selling you solutions. Then you could hire an independent auditor, who isn’t giving you a proposal for work he or she would do, but rather work that you should do. Paul Kando, a Damariscotta resident with the nonprofit Midcoast Green Collaborative, does energy audits but he’s not a contractor. “I am not there to sell something,” Kando said.

“I have been disagreeing with Efficiency Maine’s approach to this issue from the get-go,” Kando added. “For an energy audit to be worth its value, it should be independent.” An energy audit, he said, if done well, should be an educational tool. Among the things you might learn? What you could do on your own and what you need a professional for. Kando told me that in his experience, a woman who is the head of a household, as I am, tends to be upsold on weatherizing services. I’m not going to be that woman.

LOOK AT YOUR BASEMENT

A big proportion of my proposal’s cost revolved around insulating the cellar, including spray foam up the walls, a vapor barrier on all exposed floors, foam insulation on the rim joists and top 5 feet of all main walls. (The spray foam application mysteriously required removing some interior bricks, which I was welcome to do or which they’d do for me at a rate of $35 an hour. Not happening.) That estimated cost was $4,710, and that was before we even touched the crawl spaces (more on that below). Why so much on a place that houses the boiler, water heater and a motley collection of abandoned paint cans that pre-date my ownership?

“We do find that most people get the message and know that when they go outside they should be putting on a hat and they should be insulating the attic,” Stoddard said. “What most of them don’t have is anything in the basement.”

Efficiency Maine’s studies have determined that “a very high percentage” of Maine’s housing stock have little or no insulation in the basement. Wool socks, if you will. But it is one of the most effective means of weatherizing one’s home, he said. Cold air sneaks in around sills and chimney chases and is drawn in through the ground. All of it travels upward into the warm house and then onward to the attic, where it is lost.

My cellar has a dirt floor, hence the inclusion in my proposal for a vapor barrier, which would reduce the air flow coming into the basement, as well as harmful gases (like radon, which I don’t have a problem with). But DeWitt Kimball said with the limited budget I’m working with, he’d suggest focusing cellar work on air sealing the rim joist pockets and quickly to improve my cellar situation by installing a dehumidifier to ensure that the rising air won’t be moist air (to keep down the possibility of mold). “That might add $9 to the monthly electricity bill,” Kimball said. That’s triage, he said, while I focus on the most important work, namely the attic. The more moist air that gets into the attic, the more likely I am to have ice dams.

My ice dams, by the way, are epic.

SEALING THE THERMAL ENVELOPE

If you go the Efficiency Maine route, the first thing you’ll do is some air sealing. To qualify for a rebate, with the blower door test you immediately get six hours of air sealing work done, which should cost about $600. “We pay $400 incentive toward that, makes an immediate difference and helps inform the consumer,” Fischer said.

The warmed air exits through the attic, but it’s just as important to identify where the air is coming in. Some of the obvious spots a contractor might be hitting in those six hours? Openings around oil fill lines or wiring. Or maybe it’s a door that isn’t thick enough or has settled in a way that creates a gap. I’ve got a lot of those (the proposed cost for improving them was to be $875).

Unless you’ve got broken panes of glass or obvious gaps in the caulking, window work is unlikely to be a priority.

“People often think, ‘I just replaced my windows so now my house must be energy efficient,'” Fischer said. Sorry, not the case: “The payback for energy savings on windows is measured in decades.” It shouldn’t be your first choice or even your second choice on a weatherizing to-do list. If you have terrible windows (I have a few), by all means replace them, but don’t expect a payback, he added.

If replacing them isn’t an option, reusable plastic framed interior storms are a good alternative (and community groups often sponsor building days for those who need them). “Those can be cost-effective,” Fischer said. “But it becomes a seasonal activity.” (Unless you are really lazy and don’t take them down.) There’s also the tried-and-true method of taping them over with bubble wrap or the plastic wrap that comes in kits at the hardware store. Just don’t blow your money on gorgeous new wood-framed windows for energy reasons.

ZIPPING UP THE COAT

The bulk of my house is on a foundation, but like many old Maine homes, there are jerry-rigged additions, like the bathroom built into the barn and the kitchen that straddles a dirt crawl space. It’s a nasty place, and I am highly suspicious that it is home to various animals, including the skunk who recently sprayed the dog. The bill to wrap plumbing lines in insulation, spray foam insulation on the bottom of all the floorboards and put rigid foam between the joists would be $2,730. Because this is the coldest room in the house, I’d be tempted to blow some of my budget on this, or a variation of this, and skip the cellar work or at least put it off.

If I were aiming for that $500 rebate on cellar insulation, I’d have to do both at the same time though, because the Efficiency Maine incentive is for doing the entire perimeter. Otherwise, “It’s like putting on a coat without fully zipping it up,” Fischer said. “It’s good but not as helpful as zipping it up.”

This is when he reminds me that Efficiency Maine gives unsecured loans of up to $15,000 over 10 years at a 4.99 percent rate.

LAYERING WITH BLOWN-IN INSULATION

The biggest single ticket item on my proposal was for $7,665 to remove parts of my siding, drill into the walls and blow in 2 inches of dense-pack cellulose, then put the siding back on.

Blown-in insulation is, to my mind, the most fearful component of weatherizing. A house the age of mine could very well have nothing in its walls but old newspapers or weird items people wanted to get rid of (a friend’s house in Rockport had walls full of old shoes – apparently a cobbler’s idea of insulation). But thanks to a bathroom remodel, I knew that insulation had been blown in at some point. It had definitely settled, but who knows to what extent? While Efficiency Maine encourages this as an important part of the overall plan, I’m not making it a priority now.

That’s partly because I have a lottery-winning fantasy (I am a Mainer after all) whereby I will remove the ugly shingles, restore the clapboards underneath and in the process, wrap the whole exterior in Tyvek, a moisture barrier that would make future paint jobs last longer and give my house a cozy cloak.

It’s also because I’ve absorbed the lesson that my hat (attic), feet (basement) and unzipped zippers (air holes and doors) should be my winter priority.

Moreover, there’s no cookie-cutter method for weatherizing, experts say. Or time frame. It makes a big difference to do it all at once and would be ideal for consistent heat throughout the house, “But you can do these things in stages,” Fischer said.

That 1820s Cape of his? He’s been working on its energy efficiency for a decade now and has reduced his energy impact by 75 percent over that time frame. Slow and steady can win the race.

Send questions/comments to the editors.