SEARSPORT — The BBC Amber is at the dock on an early August afternoon, unloading wind turbine tower segments bound for the Passadumkeag Mountain wind project in Grand Falls Township, 70 miles to the north.

At 14,000 tons, it is a relatively small vessel, drawing just 24 feet on arrival, and was able to transit the channel to the Searsport, located at the head of Penobscot Bay, without concern for the 10-foot tides or high spots, where as much as 4 feet of silt has fallen into the channel since it was last dredged a half-century ago. But on both the day before and the day that followed, two 23,000-ton oil tankers had been forced to wait for a rising tide to proceed into the port, where oil, gasoline, road salt, wood pulp and other cargo is offloaded, much of it bound for the landlocked interior.

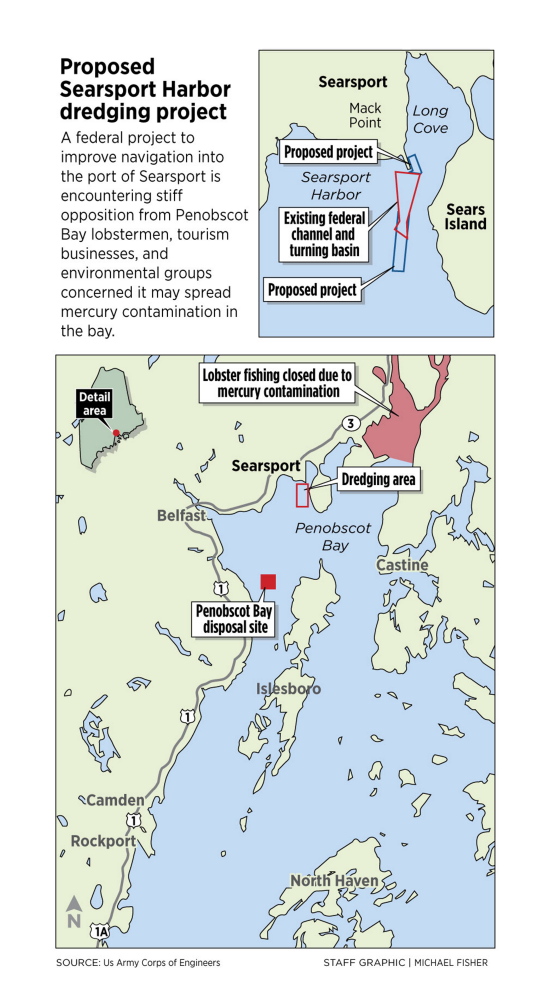

But an extensive dredging project proposed to improve and upgrade Maine’s second-busiest port has raised alarm bells up and down Penobscot Bay, where fishermen, shellfish farmers, owners of tourism-dependent businesses, and environmentalists fear it will trigger an ecological and economic catastrophe.

“If you sat down and tried to find a way to guarantee you would contaminate the entire food web with methyl mercury, they’ve come up with it,” says Kim Ervin Tucker, the Lincolnville attorney representing many of the opponents, including local lobstermen, businesspeople and the Sierra Club. “You can accomplish the project’s goals in a smarter, cheaper way that doesn’t put existing lobstering and tourism and other industries at risk.”

The port, created in 1964 when ships were smaller and safety requirements laxer, is long overdue for an upgrade, says David Gelinas, president of the local pilots’ association, who is thrilled that the Army Corps of Engineers has proposed to improve the approaches to the port, increasing the design depth from 35 to 40 feet and substantially widening the turning basin.

Anything less, Gelinas says, will compromise the long-term survival of Maine’s second busiest port. “Economically, it’s a slow strangulation,” he says. “If you’re stuck back in the ’60s, you won’t be a very competitive port very long in the future.”

BUSINESS VS. ENVIRONMENT

John Henshaw, director of the Maine Port Authority, predicts the upgrades would help attract new business to the port and the vast tracts of central and northern Maine it serves via railroad connections that run right to the bulk cargo dock. Look to the proposed wood chip plant in Prospect, he says, which would employ dozens and export its product to Europe from Searsport.

“The status quo is not a growth strategy,” he says of critics’ plans to reduce the scale of the dredging. “The shipping industry has changed a lot in the 50 years since the channel was designed and we need to accommodate those changes.”

Opponents of the project – which has to obtain permits from the state Department of Environmental Protection to proceed – question whether it needs to be as extensive as the Army Corps of Engineers has proposed, especially given the environmental risks.

At issue is the waste product: nearly a million cubic yards of material to be dredged from the port area, at least some of which is contaminated with mercury and other toxins released by polluters along the Penobscot River, the mouth of which is located adjacent to the port.

The area to be dredged is 3 miles west of the mouth of the Penobscot River, where state authorities have banned lobster and crab fishing since February 2014 after crustaceans in the area were found to have high levels of mercury in their flesh.

The lobsters and crabs had been tested as a result of a court order in a federal suit against the former owners of the HoltraChem plant in Orrington, a bleach-making facility which released large quantities of mercury directly into the river between 1967 and 1982. On Wednesday, a judge ordered the firm that owned the plant at that time, Mallinckrodt, to pay for an engineering study on how to remove the toxic heavy metal from the lower 20 miles of the river, a project estimated to cost $130 million.

Kevin Yeager, the University of Kentucky geologist who served as the court-appointed sedimentation expert in the HoltraChem case, issued a report in July 2014 taking the Corps to task for relying on faulty testing of the sediments in the Searsport dredge area. The Corps tests, he wrote “suggest these sediments are quite contaminated” but that proper testing and analysis was “highly likely” to show an even greater degree of contamination.

The Corps has argued that the sediments are suitable for disposal at the western Penobscot Bay site. Officials at its New England regional office said they could not respond to critics’ comments at this time.

Given the contamination, many around Penobscot Bay fear the proposed disposal site is not an appropriate place for it.

According to project documents, the Corps wants to remove the most contaminated material – surface material with high levels of heavy metals and polycyclic hydrocarbons – and dump them into a series of deep, cone-shaped pockmarks in the bay’s floor halfway between Islesboro and the Northport shore. They would then cover them with cleaner dredge material, sealing it away from the environment.

OUTRAGE OVER PLAN

But Joe Kelley of the University of Maine, a former Maine State Geologist who has mapped the bay’s bottom, has said these pockmarks are geologically unstable and formed by the venting of methane gas. Scouring by ocean currents would likely resuspend any material stored in them. At a June 9 hearing, he testified that the Corps in fact knew this, and in the 1990s had rejected them as a suitable place to dump dredge spoils in the 1990s.

“I was surprised by this (new) proposal in light of the prior rejection of this area … and the known risks of using this area for this purpose,” he stated. “The possibility of resuspension of buried contaminants, including HoltraChem-contaminated material, makes the use of pockmarks in this area even more dangerous, and threatens the reputation for wholesomeness of all Penobscot Bay fishing resources.”

Armindy McFadden, who manages a Lincolnville Beach restaurant and co-owns a Northport mussel farm located just 5,000 feet from the proposed disposal site, says it’s an outrageous idea. “Generations of people have been dumping stuff in that harbor and now they want to put it in a 400-foot methane hole that geologists have said for 20 years is too terrible to use,” she says.

“People aren’t going to come here if the think the bay is polluted, and if the brand name of Maine lobster is tainted in any way, shape or form, than our entire economy in Maine as we know it is going to be affected,” she added. “This is the first time the Sierra Club and the lobstermen and all these businesses have been on the same page. This is one central issue that this entire area feels strongly about.”

LOBSTERMEN FEARFUL

Steve Miller, executive director of the Islesboro Islands Trust – which is intervening against the project before the DEP – agrees. “The science is telling us the material would probably be redistributed in the water column and carried south over lobster feeding areas and so forth,” he says. “It’s an experiment, and we don’t want to be treated like a guinea pig up here.”

Belfast lobster fisherman David Black fishes the area around the proposed disposal site and says area lobstermen fear for the destruction of the fishery. “We understand that dredging is an important part of keeping working waterfronts open on the coast of Maine,” Black says. “However, we don’t like the idea of dropping a million cubic yards of dredge spoils right in the middle of upper Penobscot Bay.

“There is an alternative which is much less environmentally damaging than the one they are proposing,” he adds.

Black and the other opponents want the DEP to reject the plan, arguing the port’s needs can be met under an alternate scheme that would dredge about a tenth as much material, reducing the danger of contamination. This proposal would deepen the berth at the Searsport dock but would not expand the turning basin or deepen the channel beyond 35 feet.

They have been urging the DEP to consider the plan – created by Dawson & Associates, a Washington, D.C., consultancy focusing on Corps projects – which they say would be cheaper and would allow the port to meet current traffic needs, even if some vessels have to play the tides.

“We’re not objecting to bringing in deeper draft vessels; we say you can bring them in in a smarter, cheaper way without stirring up the mercury everyone knows is there,” says Tucker, the lawyer.

HURDLES TO CROSS

Port interests are unimpressed with the “Dawson alternative.” Henshaw, the state’s ports director, calls it “a recipe for the status quo.”

“Essentially you’re saying that you don’t even want to accommodate the existing traffic, and we’d see declines of traffic over time,” he adds.

The project requires DEP permits to proceed, and outgoing DEP commissioner Patricia Aho has said for months that she intends to hold adjudicatory hearing on the project, but has yet to announced a date. Department spokesperson David Madore said the department could not discuss the project because it would “compromise the integrity of the hearing process.”

An official at the state Department of Marine Resources said staff there were compiling a report for DEP on how the project would impact area fisheries, and that it would be completed in several weeks.

The Searsport project manager at the Army Corps of Engineer’s New England District Office in Concord, Massachusetts, Barbabra Blumeris, also said she couldn’t comment, apart from describing the process. Even if the project receives DEP approval, she said, it still had a number of hurdles to cross: approval from an internal review board and the agency’s chief of engineers, authorization from Congress, appropriation of Congressional funds, the design of the detailed engineering plan, and sending the project out to bid.

Even in the best case scenario, she said, the project was not likely to start earlier than November of 2018. “We have lots of work to do,” she noted.

Send questions/comments to the editors.