DEER ISLE – Jane McCloskey wrote a love letter to her father with her first book. This time around, she wrote a love letter about his art.

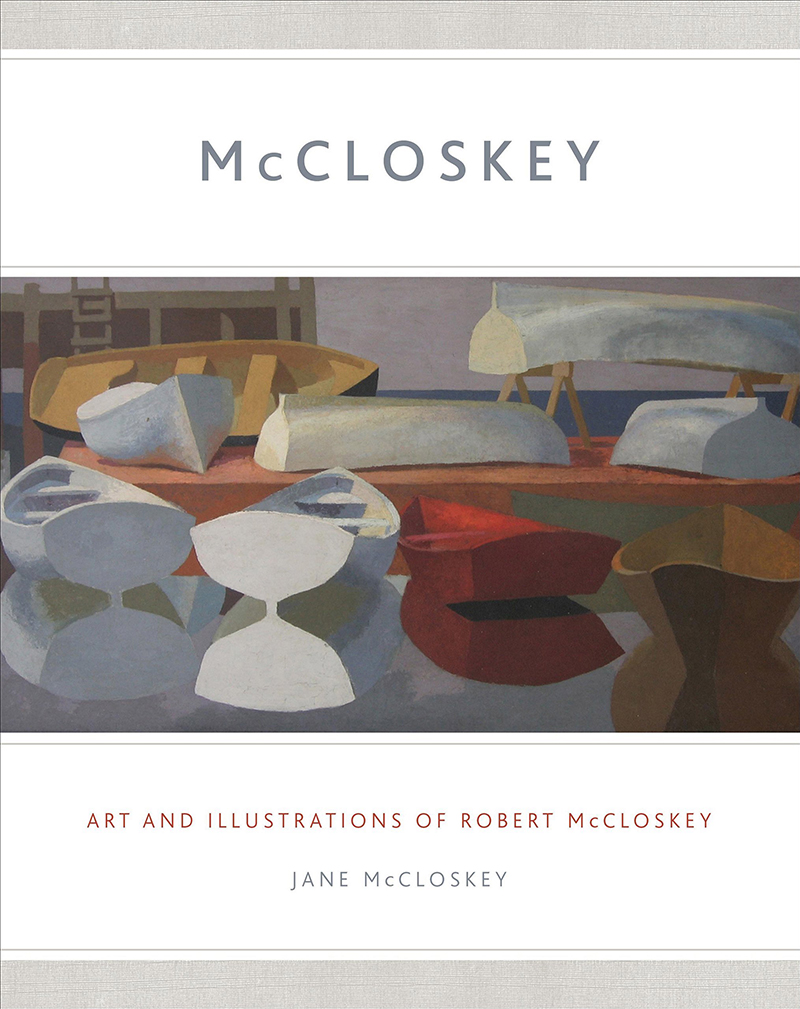

“McCloskey: Art and Illustrations of Robert McCloskey” focuses on the paintings that the book author and illustrator made for himself and for the pure joy of artistic expression.

Jane McCloskey wrote a little about her father’s private paintings in her first book, which was published in 2011. The new one expands on that earlier effort and offers new insight into the man who is beloved for writing and illustrating “Blueberries for Sal,” “Make Way for Ducklings” and “One Morning in Maine.” Intensely private and distressed by the intrusion of fame, McCloskey rarely showed his other work to anybody. After their father died in 2003, McCloskey and her sister, Sally, found paintings stashed in closets, under stairs and hidden in nooks and crannies throughout his Deer Isle home. It was almost as if he didn’t want people to find them, she said.

“Most people know my father for his books,” she said. “But these paintings are very different from his books. They’re angular, simplified and spare. I wanted to highlight his art and compare the sketches that were found in his sketchbook with the illustrations that were published. I think people might be surprised by what they see.”

She certainly was.

McCloskey spent the past few years going over her father’s paintings, trying to understand his technique while learning about art history. She’s not an art critic and freely admits the visually creative gene “skipped a generation.”

“He’s a hard act to follow. When I was 4 or 5, I thought I might be an artist. But no,” said, laughing.

Now 66 and living in Deer Isle not too far from the island home where she and her sister spent summers with their parents, McCloskey hesitates analyzing her father’s work too much from a critical perspective. Instead, she introduces it, explains it and provides context. The book also includes sketches and reproductions of illustrations McCloskey made for his children’s books, which earned him two Caldecott Medals and legions of dedicated fans.

McCloskey rarely talked about his art, his daughter said. During his career as an illustrator, he never referred to himself as an artist. “He never sold anything, and never really tried,” she said. “It was all about the books.”

Though he didn’t talk about art much, he did teach his daughter how to look and how to see. Most people do not know how to observe, he told her when she was 8. They allow their idea of the world to prevent them from seeing the world as it really is, he explained. When people draw, they draw their perception of an object or what they think it should look like, and not what it actually looks like.

“For example, when I was 8 and was drawing a girl, I drew her eyes about one third of the way down from the top of the oval that was her head, because I thought of eyes as being in the upper part of the head,” she writes in the book. “Looking at my drawing, my father said that in fact, eyes are almost exactly half way down the head oval.”

After finishing her first book about her father, McCloskey delved into the second. Her editor was keen for follow-up, but McCloskey worried about repeating herself. To prevent that, she learned as much as she could about how her father worked during his early days in Ohio through the time he moved East and eventually bought a summer home on an island in Maine.

Robert McCloskey published “Make Way for Ducklings” in 1941, and the family began coming to Maine in 1946. “Art and Illustrations of Robert McCloskey” traces his career chronologically and geographically, highlighting changes and evolutions in his art as he matured and moved from the Midwest to Boston, New York and Maine, and later to Mexico and the Caribbean. Jane McCloskey dedicates two chapters to art theory and his practice, including his interest in design and a concept known as dynamic symmetry that guided much of his work. Using illustrations from her father’s books, she demonstrates how he employed the concept, which is a proportioning system rooted in rectangles and driven by mathematics.

McCloskey was generally aware of her father’s obsession with math and its relationship to art while he was working, and she learned about it firsthand when she began building her home. She showed her father an early design for the cabin, at 24-by-16 feet, or a proportion of 3 to 2. He suggested she alter is slightly, building it 26-by-16 instead and resulting in a proportion of 1.6 to 1. That nearly exactly matches the proportioning system her father employed in his art.

Robert McCloskey painted his environment. The book is filled with images of boats, gulls and island homes. He used bright colors and worked in a range of media, including pencil, charcoal, watercolor, oil, acrylic and casein. Later, he made puppets.

Learning about her father’s art and writing about it has helped McCloskey reconcile a difficult and challenging relationship. She got along well with her father when she was young, but they drifted as adults. She attributes part of their schism to a nervous breakdown she said he suffered when the family lived in Mexico.

She’s never understood what happened to her father and speculates in her book that it might have been professional crisis. He had achieved fame and was widely recognized for his work, but might have feared reaching the pinnacle of his professional life at age 44. There was no way to go but down, she writes.

Regardless of the cause, her father began to withdraw. And so did she. “My father turned inward, and I turned inward,” she said.

Later, when she was diagnosed with chemical sensitivities and mercury poisoning, the relationship became more strained. “My father thought I was crazy,” she said. “He was ashamed of me. It was very difficult.”

They reconciled in the years before his death, for which McCloskey is grateful.

Her father never embraced his fame, she said. As a young girl, she witnessed the effect of fame on the family. One spring in the late 1950s, they had just come to Maine from Mexico, where they had spent the winter. When they arrived at Deer Isle, fans were waiting for them. “Time of Wonder,” which featured their Deer Isle home and environs, was McCloskey’s latest book. People were able to locate the family home based on the illustrations, McCloskey said.

Her father was horrified. “He just wasn’t comfortable with fame, and I believe that was one of the reasons he went underground,” she said.

As an older woman, McCloskey is able to look back at her father fondly. For one thing, she’s come to respect the aging process and how people navigate end-of-life journeys. McCloskey plays guitar and sings, and lately has joined a hospice group that performs songs to people who are dying. It’s one of the most humbling things she’s ever done, she said.

“When people are dying, it’s an honor to be there,” she said. “It’s a way of coming to terms with my end of life. The golden years, they become precious.”

In many ways, she’s gotten to know her father better now than ever, because she understands his art in ways she didn’t before. And making art, she said, whether for his books or for pleasure, was central to his existence.

Send questions/comments to the editors.