FARMINGDALE — An invasive pest is on Maine’s doorstep and forest health experts are stepping up efforts to detect the destructive bug as soon as it crosses the border.

Last month, Belknap County became the latest county in New Hampshire to begin restricting the movement of firewood and other wood products. The quarantines are aimed at slowing the spread of the emerald ash borer, a small green beetle that has killed tens of millions of ash trees across the U.S.

Maine has yet to record any infestations of the emerald ash borer, but the beetle’s rapid spread throughout the U.S. and its presence in New Hampshire just 20 to 30 miles from the Maine border mean it is only a matter of time before the borers arrive in Maine.

“We are trying to prepare for the inevitable,” Dave Struble, chief entomologist at the Maine Forest Service, said recently. “I would like to think that it is not inevitable, but it is.”

First documented in Michigan in 2002, the emerald ash borer has since spread to 24 states and at least two Canadian provinces, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. In New England, infestations have been reported in New Hampshire, Massachusetts and Connecticut.

A native of Asia, the beetles lay eggs on all species of ash trees that occur in the United States. The larvae then tunnel under the trees’ bark, with infested trees typically dying within three to five years. Although there are methods to control the spread of the emerald ash borer, experts have yet to devise a way to eliminate the pests once they are established.

Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry Entomologist Colleen Teerling shows samples of the Emerald Ash Borer in Augusta. Whitney Hayward/Staff Photographer

That reality is forcing forest managers in Maine and throughout the country to try to respond to new infestations as quickly as possible to contain the beetles.

Kyle Lombard, a forest entomologist with the New Hampshire Division of Forests and Lands, said he and his colleagues feel “pretty happy” that the pest has only spread to roughly 10 towns in four counties since it was first discovered 2-1/2 years ago in a tree along Interstate 93 near Concord.

“Since 2013 when we first found it, we have not seen it spread throughout the state,” Lombard said.

A VALUABLE RESOURCE THREATENED

Although Maine has lower densities of ash trees than other states, ash is an important niche wood used by traditional basket weavers within Maine’s Indian tribes as well as by manufacturers of furniture, baseball bats, canoe paddles, snowshoes and other products. An estimated $140 million in ash is harvested in Maine annually. Ash trees also dot many main thoroughfares and parks throughout the state.

To detect the emerald ash borer, Maine foresters and entomologists have deployed special purple kite-like traps hung in trees that emit pheromones attractive to the beetles. They also create “trap trees” by stripping some bark in order to stress the trees, which makes them more attractive to any beetles in the area. Crews then cut down the tree during the winter to check for any larvae.

But emerald ash borers’ diminutive size make them difficult to find, even with their iridescent armor. So biologists also turn to an expert beetle hunter to do the work for them.

‘WASP WATCHERS’ LOOK FOR BEETLES

Late Tuesday morning, Maine Forest Service entomologist Colleen Teerling headed to a seemingly unusual place to look for a beetle threatening Maine forests: a baseball field at Hall-Dale High School in Farmingdale just a few miles from the State House.

Armed with her well-trained eyes and a bug net, Teerling scanned the dirt between first and second base for a type of wasp that preys on an iridescent-brown beetle relative to the emerald ash borer – and the borer itself when it is present. Once a visitor knew what to look for, it was easy to spot the half-inch to three-quarter-inch wasps lumbering toward their individual underground nests lugging a freshly paralyzed beetle.

Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry Entomologist Colleen Teerling examines a Cerceris Fumipennis, or the Smokey-winged Beetle Bandit, a type of wasp whose hunting is currently being monitored to see if they catch Emerald Ash Borer beetles. Whitney Hayward/Staff Photographer

Teerling and other “wasp watchers” try to collect or at least inspect 50 preyed-upon beetles from each site during a visit. If there are no emerald ash borers in the batch, that means there’s not likely a borer infestation in the area because otherwise the wasps would have noticed the bright green beetles.

“If we find even one beetle, then we would know that we have an infestation around here,” Teerling said. More detailed surveys would follow until the infestation site is found. The response team would then decide how to manage the site. Options include cutting down all ash trees in the area for more severe infestations or removing the larger trees capable of hosting the larvae.

“If we don’t do something, we know we can lose all species of ash throughout North America,” Teerling said.

NEW HAMPSHIRE FIGHTS THE SPREAD

Although the emerald ash borer does expand its range on its own, more often than not it is believed to get human help by hitching a ride on firewood, ash wood-products and ash nursery trees. That is why Maine bans the importation of firewood into the state, except if it has been heat-dried by a USDA-certified facility. Those restrictions are also intended to stem the movement of another invasive pest, the Asian long-horned beetle, that is spreading in New England.

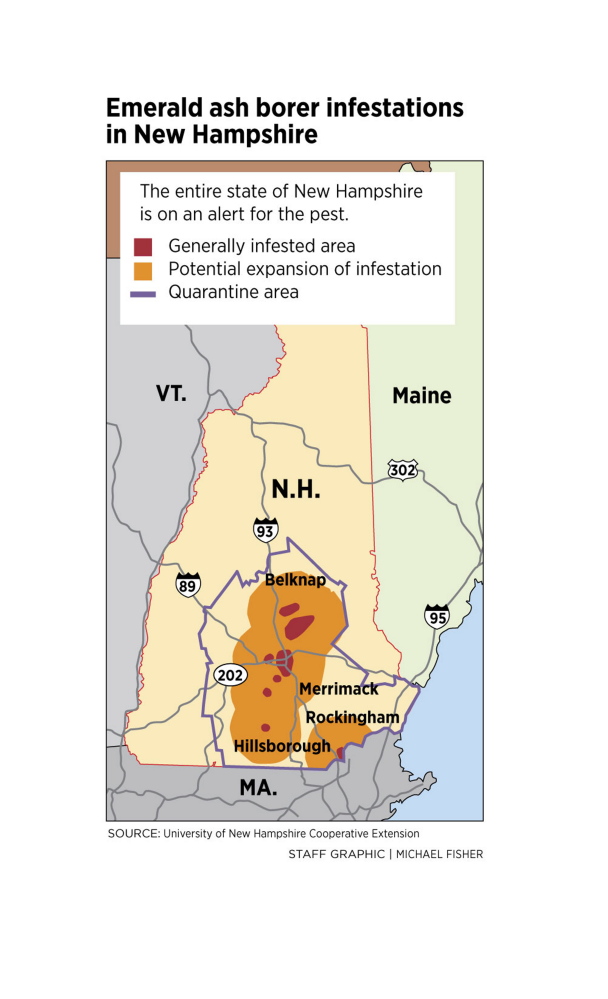

In New Hampshire, officials now ban the movement of firewood and other “regulated materials” out of the four quarantined counties of Belknap, Rockingham, Hillsborough and Merrimack, all located in the southern portion of the state. New Hampshire and Maine entomologists also work together, along with their federal counterparts at the USDA and the U.S. Forest Service, to collaboratively monitor and control the beetles.

New Hampshire also has a three-tiered management system intended to guide landowners living within or near infestation areas. But a big part of the focus in both New Hampshire and Maine is on outreach and education, which Lombard acknowledged can be a challenge at first.

“People are very busy these days. And talking about trees and insects, it can be very difficult to get people’s attention,” Lombard said. But once they learn about the threat posed by the pests and the steps they can take to reduce the spread, most people seem to go along with the plans, he said.

KEEPING AN EYE OUT

Back in Maine, the Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry is training volunteers on how to monitor for the emerald ash borer and other invasive pests, as well as how to help educate others about them. There are current training sessions scheduled for Aug. 25 at the University of Maine Farmington and for Sept. 15 at a yet-to-be-determined location in York County.

Forester Jeff Wiegert of the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation points out the markings left from emerald ash borer larvae on an ash tree at Esopus Bend Nature Preserve in Saugerties.

Forest and insect specialists have deployed about 900 special emerald ash borer traps around the state in order to detect the bugs and have spent the summer doing “biosurveillance,” monitoring of 20 to 30 sites with the smokey-winged beetle bandit wasp.

“At this moment we haven’t found any in Maine,” said Struble, chief entomologist for the Maine Forest Service. “I’m not convinced they aren’t here yet, but (the infestation) is sufficiently low that it has escaped detection.”

For more information on the emerald ash borer in Maine, go to www.maine.gov/dacf/php/caps/EAB/index.shtml

Send questions/comments to the editors.