Gov. Paul LePage’s habit of sending colorful, blunt and occasionally perplexing handwritten notes to legislators and constituents has been portrayed as yet another facet of his distinctive, controversial style of governing.

But on top of being highly personal, the governor’s method of communicating is also highly perishable.

Neither LePage nor his staff apparently makes copies of his letters – even when the topic at hand involves state policy or other matters of public interest connected to his official duties as Maine’s chief executive.

For example, LePage’s threat to strip Good Will-Hinckley school in Fairfield of $530,000 in state funding if it hired House Speaker Mark Eves as its next president was communicated in a handwritten note from the governor to the school’s board chairman, Jack Moore. Moore has said he may have discarded the note, and a copy was not among the documents the governor’s office released to the Portland Press Herald last week in response to a Freedom of Access Act request for all records related to the Good Will-Hinckley matter.

The administration has taken the position that LePage’s handwritten notes are not subject to the public records law because they are personal communications, not official business.

But current and former state archivists disagree, as do experts on the Freedom of Access Act.

Disputes about LePage’s notes illuminate weaknesses in compliance and enforcement of Maine public records law and archiving program.

The deficiencies – some of which were detailed in a report this year by the Legislature’s watchdog agency – are sweeping and longstanding, leaving gaps in the historical record and the public’s understanding of how its government works and how decisions are made. In some instances, the state’s spotty adherence to record retention policies has led to the destruction or loss of records that might explain or resolve controversies and hold elected officials and their subordinates accountable.

“These handwritten notes are on the governor’s stationery and they are dealing with public business,” said Sigmund Schutz, a board member of the New England First Amendment Coalition and an attorney who represents the Portland Press Herald in cases involving FOAA. “As a general matter, if they’re not real personal – a birthday card, something like that – and they’re responding to constituent inquiries or communications, they’re public records.”

David Cheever, the Maine state archivist, said the governor should have copies of his notes.

“When you get into certain positions, like the governor, gubernatorial correspondence is generally considered to be archival,” Cheever said.

SOME NOTABLE NOTES

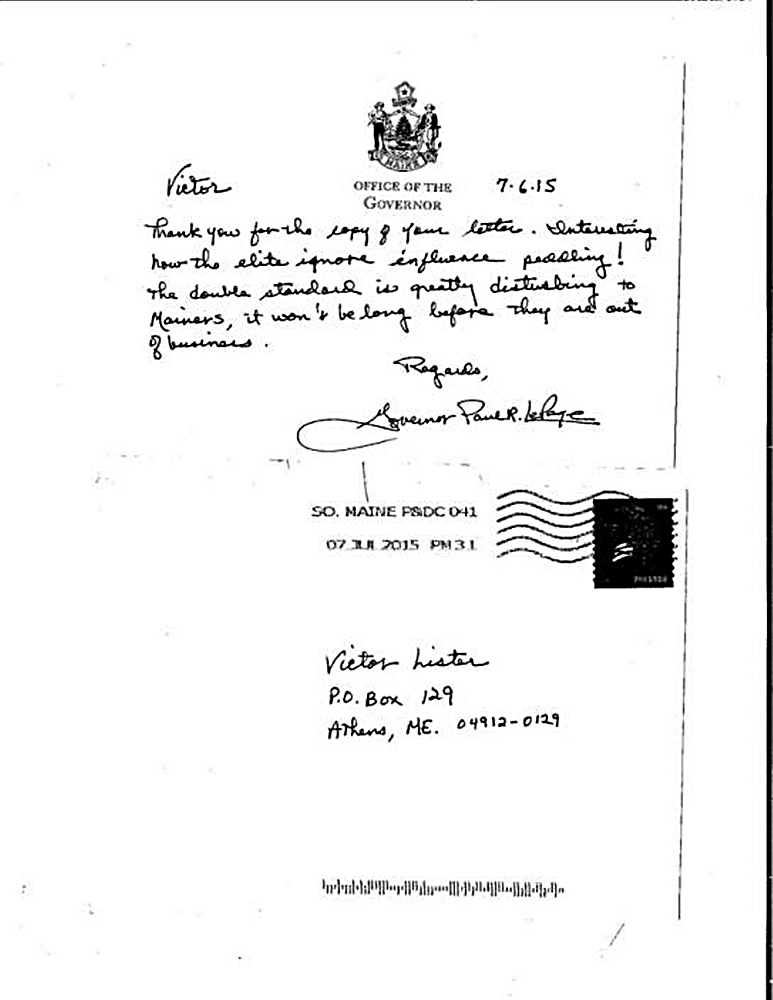

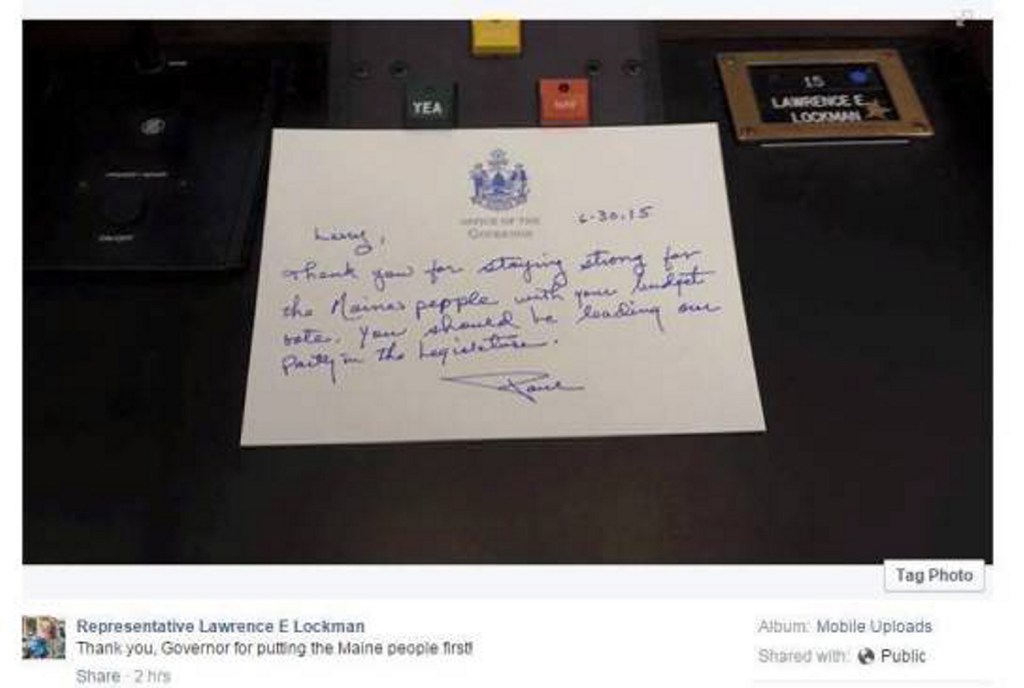

LePage has been sending handwritten notes to lawmakers, constituents and lobbyists since he took office in 2011. Sometimes the missives stay secret. Sometimes they make headlines.

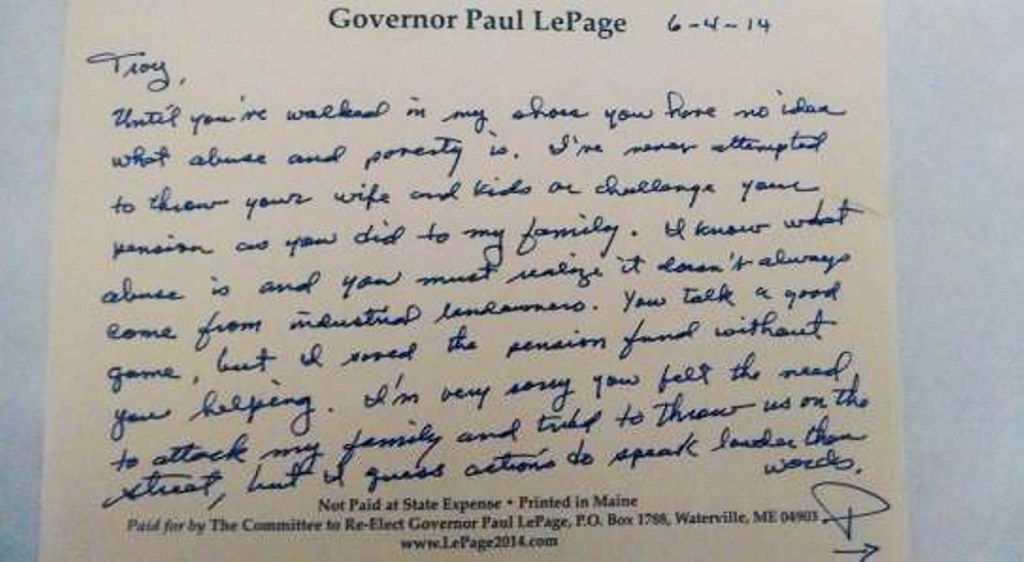

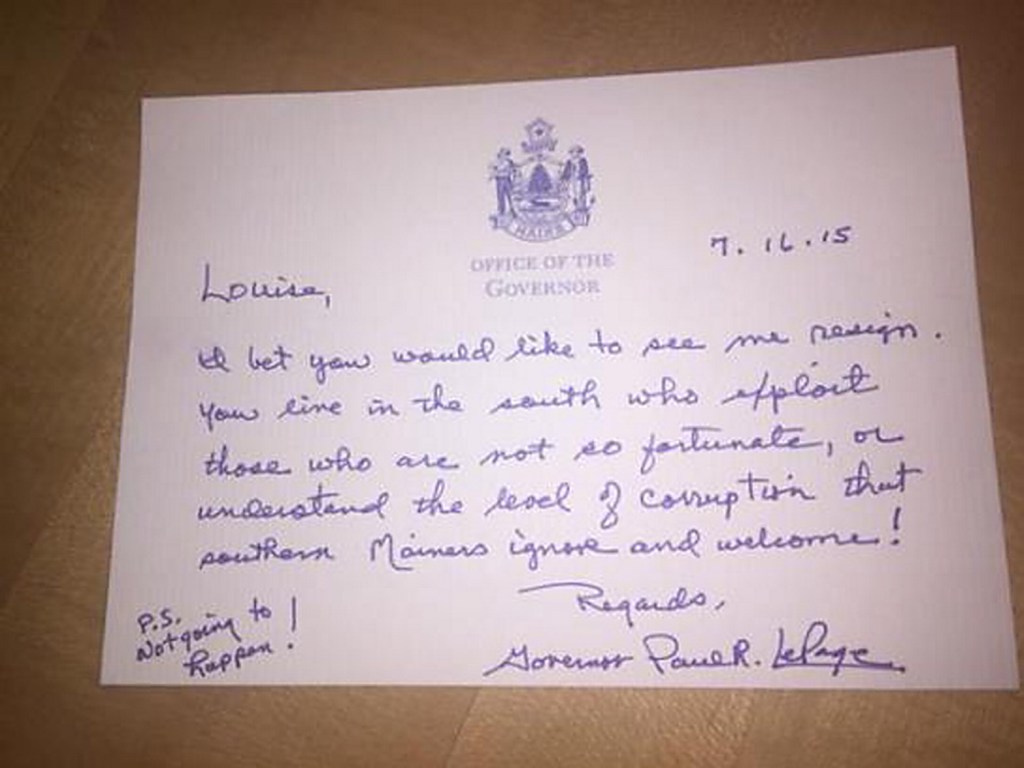

Last month the governor was widely criticized for a note he sent to Louise Sullivan, a retired librarian from Cape Elizabeth. Sullivan had sent a letter to LePage urging him to resign. The governor fired back with a sharply worded note on his official stationery accusing Sullivan of exploiting “those who are less fortunate” and failing to understand “the level of corruption that southern Mainers ignore and welcome!”

As for Sullivan’s call for LePage to resign?

“Not going to happen!” the governor wrote in a postscript.

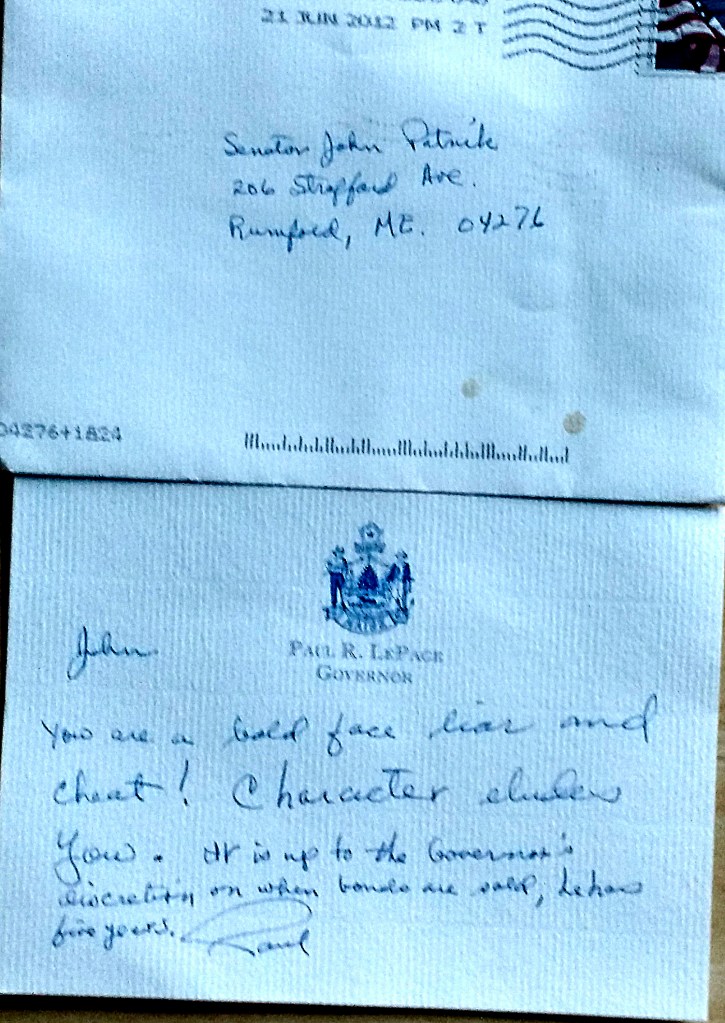

In 2012, Democratic state Sen. John Patrick received a mailed postcard from LePage at his home in Rumford. Patrick and other Democrats had been critical of the governor’s refusal to sell voter-approved bonds.

“You are a bold face liar and cheat!” LePage wrote. “Character eludes you. It is up to the governor’s discretion on when bonds are sold, he has five years.”

The letter to Patrick is posted on a progressive website under the heading, “Notes from the Edge.” The collection of notes range from the governor’s letter to loyal Republican lawmakers to an editorial cartoon that he had his education policy adviser forward to Maine school principals.

Officials in the LePage administration describe the notes as the governor’s fulfilling his desire to interact with Mainers.

“We have a governor who is very in tune with Mainers and is very concerned with their suggestions,” said Adrienne Bennett, the governor’s spokeswoman. “He does feel like it’s his responsibility to respond.”

Although the governor’s notes can be dismissed as another quirk in his complex, and sometimes polarizing, public persona, they may also reveal his view of the state’s public records law. As a gubernatorial candidate in 2010, LePage vowed to become the most transparent governor in state history. However, he was quick to sour on the state’s public records law after taking office.

At one point he called FOAA requests “a form of internal terrorism.” He has since publicly acknowledged that he has instructed staff to avoid conducting too much state business over email. In 2014, when asked by a liberal activist to respond to a FOAA request, LePage warned that the resulting documents would be written in a coded shorthand that only he understands.

It’s unclear if LePage’s prolific letter writing is designed to skirt the state’s FOAA law. Bennett could not explain why the governor writes letters.

“I don’t think he’s ever turned on a computer in his office,” she said.

Current and former state archivists say LePage should be keeping copies of his handwritten notes.

“Handwritten or not, it’s a public record,” said Jim Henderson, who was state archivist between 1987 and 2007. Henderson said that the notes should go to the archives, either on an annual basis or when LePage completes his second term.

State archiving rules require governors to designate a record-retention officer in his office to ensure that correspondence such as letters and emails are preserved. However, it’s unclear if Jennifer Tarr, the governor’s retention officer, or other members of his staff have even seen LePage’s handwritten letters before they’re sent, much less afforded the opportunity to copy them.

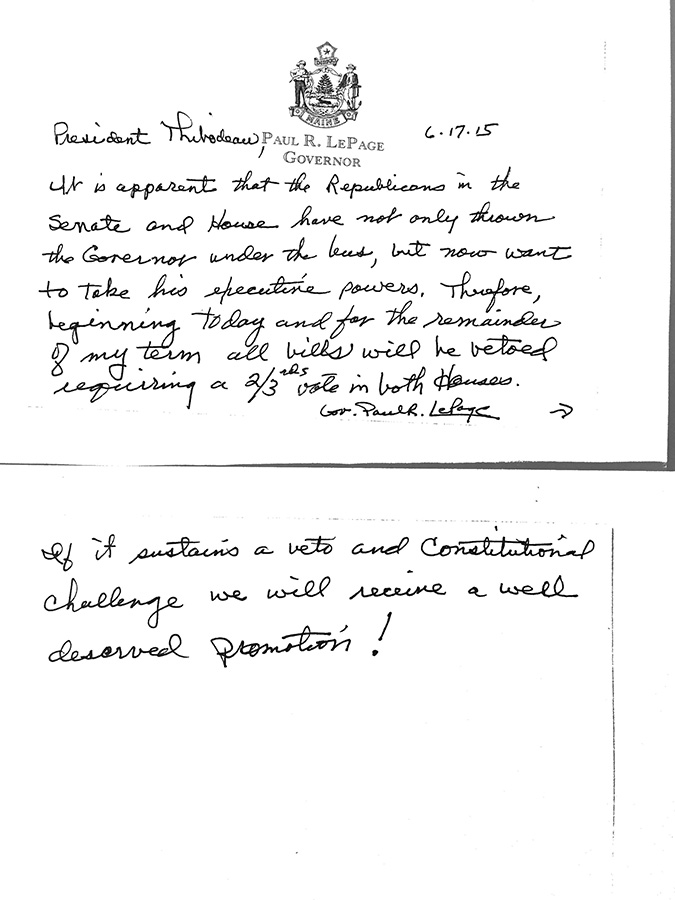

In June, the Press Herald requested a handwritten letter from LePage to Republican Senate President Mike Thibodeau. Thibodeau’s office turned over the note, which contained the governor’s vow to veto all bills through the duration of his second term. It also contained references to Republican lawmakers wanting “to take his executive powers” and getting “a well deserved promotion” if bills survived a veto and “constitutional challenge.”

When asked to clarify the meaning of the note in June, Peter Steele, the governor’s communications director, shook his head. He had never seen it before.

LePage isn’t the only governor to fire off handwritten notes.

In 1975, Gov. Jim Longley sent a letter to Arthur Ochs Sulzberger, president and publisher of The New York Times. Longley, another prolific letter writer with whom LePage is often compared, was concerned about an incoming “hatchet job” by a reporter from New York Times Magazine. The governor, in an attempt to persuade Sulzberger not to run the piece, assailed the reporter’s reputed sources, including Shep Lee, a longtime Democrat.

Lee, Longley wrote, “played the political game for his ego and self-serving prestige purposes.”

Longley’s notes were legendary. But most of them can’t be found in the Maine State Archives, which is charged with collecting and cataloging state records, including gubernatorial correspondence. Longley’s letters would not have been made public if not for the efforts of Willis Johnson, a former State House reporter who collected them for a book, “The Year of the Longley.”

Longley’s decision not to turn over his letters is consistent with many other governors, Cheever said.

It’s also consistently against the state’s archiving policy.

Schutz said it’s a longstanding problem.

“What gives?” he said. “This stuff isn’t being retained. It’s the obligation of the state archives to enforce these rules and to protect and preserve these records for posterity, for historical use, for official use.”

He added: “If the governor is writing these letters and he’s not retaining a copy of them, or not even retaining a record of having sent them, it raises a lot of questions. If it’s a legal problem, it’s really up to the state archives to address and enforce, I think. It’s also a policy issue. How does the governor even keep track of who he communicated with and what he may have said to them? It becomes a question of good governance.”

BROKEN RECORD-KEEPING

Public record retention shortcomings aren’t confined to the governor’s office. It’s a problem that cuts across many state agencies.

In April, a working group formed by the Legislature’s Government Oversight Committee found that the state’s record-retention program is in shambles. More than half of state agencies and departments did not have staff assigned to ensuring that public records are safeguarded and cataloged – even though the agencies are required to by law.

The State Archives Advisory Board, which advises state and local agencies on record retention policies, is littered with empty seats and members whose terms have expired. Record retention schedules established in the 1980s when Cheever, then-spokesman for Gov. Joseph Brennan, was working with an IBM Selectric typewriter and the Office of Attorney General used a Wang computer system, have not been updated.

“The intent of the Freedom of Access Act … is that the people’s business should be conducted openly and government records should be open to public view,” the working group report began. “While FOAA does not expressly identify the documents that must be retained in order for the public to be able to see how government agencies transact business, its purpose cannot be achieved without adequate documentation and retention.”

The record retention report was spurred by controversy. In 2013, officials at the Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention shredded documents used to justify the distribution of $4.7 million in public grants. The destruction of the documents was never disputed, but lawmakers on the Government Oversight Committee and the Office of Program Evaluation and Accountability were unable to draw definitive conclusions about who was responsible and why it happened because of the vanished paper trail.

In 2005, an investigation by Attorney General Steven Rowe found that officials within the Department of Environmental Protection unlawfully destroyed records used to justify a controversial cleanup plan in the Androscoggin River.

Former DEP chief Dawn Gallagher resigned over the controversy, which the Baldacci administration attributed to a misunderstanding of the state’s FOAA law. Gov. John Baldacci later called for additional FOAA training.

In June, the Government Oversight Committee issued a similar call to the LePage administration. A June 1 letter to the governor’s legal counsel said there are “systemic weaknesses” throughout the state’s records retention and management system. The committee requested a response from the administration by June 30. However, the administration has not yet responded, according to Beth Ashcroft, the director of OPEGA.

It’s unclear how the governor will reply, or if he will break with his predecessors and retain copies of his handwritten notes for posterity.

“It always has been a problem with governors,” said Henderson, the former state archivist. “Not every one, but some, just thought, ‘I’m the governor, I’ll destroy this or delete that.’ Oftentimes they just kind of got away with it.”

If LePage decides to follow suit, he may get away with it, too.

Cheever said the Maine State Archives doesn’t act as an enforcement agency.

“If he elects to eschew archiving his correspondence because he believes it to be incidental, we don’t have an enforcement authority to say, ‘Hey, you’re supposed to give us a copy.'”

He added: “So we don’t know what we’re missing. That’s been the case since time immemorial.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.