The painter Henry Isaacs fell asleep while driving on a New Hampshire highway on a June afternoon. His pickup truck cascaded down an embankment and rolled three times. Isaacs walked away with only a concussion, thanks largely to a burly off-duty Massachusetts police officer, who recognized leaking gas and raised the truck with his arms and body just enough for Isaacs to crawl to safety.

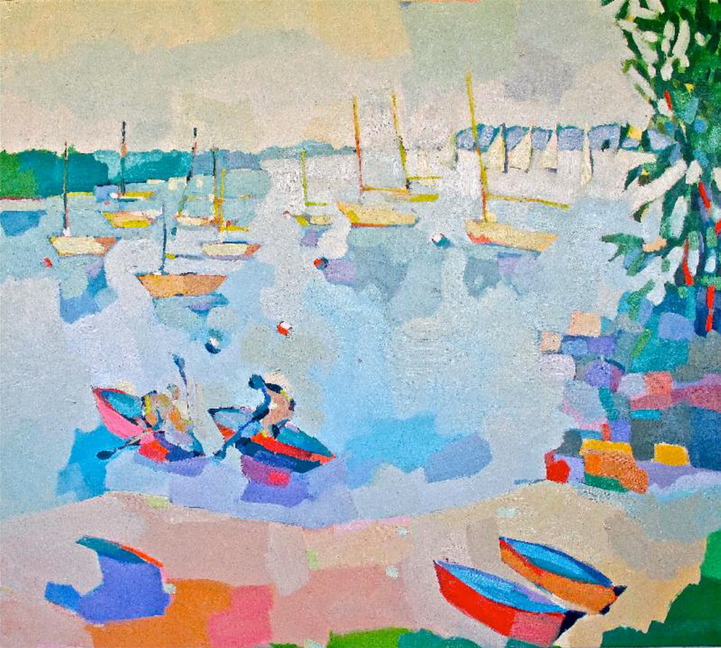

The fire that both feared never materialized, but the damage was done. In addition to totaling his truck and suffering the indignity of a foolish mistake behind the wheel, Isaacs lost much of a winter’s worth of work. He had been transporting about three dozen finished canvases – many of them large, and some sold and paid for – from his home in Sharon, Vermont, to his summer home at Little Cranberry Island. The paintings were destined for the Isleford Dock Gallery on the island and Gleason Fine Art in Boothbay Harbor, where Isaacs shows a large group of his bright, joyful canvases through September.

Many were destroyed or harmed. Isaacs fixed the paintings he could but quickly realized the finished paintings didn’t mean all that much to him, and they certainly meant more to the collectors who had already purchased them or to the galleries where the work was promised. The accident reminded him about fragility and reinforced a lesson he learned long ago from the abstract expressionist painter Jackson Pollock, who was a family friend. Isaacs didn’t realize Pollock’s lesson until the accident a few months ago: The process of painting – indeed, the privilege of painting – is far more important than the result.

“Here’s the thing about the pictures,” Isaacs said in an interview at his Portland condo, “I didn’t and don’t care. Living trumps the picture. What I am about is making pictures. The pull for me is the making of them.”

With renewed artistic vigor, Isaacs, 64, is moving forward with his career and, for the first time since he began coming to Maine 35 years ago, is focusing more of his work and home life in Portland. A landscape painter with a breezy style, Isaacs has made his life in art, early on as a teacher and more recently as a widely collected painter. He and his wife, Donna made such frequent stops in Portland on their way from Little Cranberry to Vermont that the downtown hotel they regularly stayed in honored their loyalty. This past winter, the couple bought a West End condo.

The condo comes with a bonus. Isaacs also purchased the loft of a 1797 carriage house nearby, and he plans to renovate it as his next painting studio. It will be the largest studio he’s ever worked in and will more easily accommodate the large paintings he already makes and the larger ones he has in mind.

The carriage house was part of an old estate that stretched to what is now the Western Promenade. With wide floor boards and the charred rafters of a long-ago fire, the carriage house retains stories of Portland’s past. Whether they show up in his paintings, these stories and the characters associated with them will become part of Isaacs’ future and will inform his work in ways he can only imagine, just as the characters and qualities of Little Cranberry have influenced his work since he began spending time on the island.

“I love stories about where we are, and I like uncovering stories and finding out what’s beneath the surface,” he said.

AT HOME IN PORTLAND

Isaacs is keeping his home and studio in Vermont as well as his place on Little Cranberry, but Portland is becoming the center of his artistic life. He’s always shown his work here and has outlived more Portland galleries than he can remember.

Living in Portland means less time on Little Cranberry, a decision that comes with regrets. On one hand, he misses his friends, particularly Ashley Bryan, a noted children’s book author and artist with whom Isaacs engaged in conversation and critique. They still talk nearly every day, but talking by phone isn’t the same as getting together for an afternoon cocktail to assess the day’s work. “I miss that, and I miss it deeply, because his ability to put himself in another’s artist’s shoes is extraordinary,” Isaacs said. “My paintings are filled with ideas stolen from him, especially ideas about color and pattern and flat and deep space and all of those concerns.”

On the other hand, Isaacs has Portland. It’s the largest city he’s lived in in many years and a city he has grown to love. He feels stimulated by the community of artists and the general bustle. It’s not unusual to see him walking the streets in search of ideas or painting on the Eastern Prom.

Isaacs was born to paint. His parents both painted and were interested in the arts. His mother, Charlotte, graduated from the Corcoran School of Art and later in life became a printmaker. His father, Reginald, taught urban and regional planning at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where Isaacs grew up after moving from the Midwest at age 2. One of Reginald Isaacs’ closest friends was Pollock. Though he was only 5 when Pollock died, Henry Isaacs remembers going with his father to Pollock’s studio and to gatherings with Pollock and his wife, Lee Krasner.

Isaacs grew up with Pollock paintings in his home. At one time, his father owned 17 Pollock originals. His father gave away 14 after Pollock died, including a gift to Harvard’s Fogg Museum. The other three were stolen from the family apartment in Cambridge in the mid-1970s in a caper that drew national attention.

Isaacs has never been fond of Pollock’s work and grows quickly bored by a museum show of Pollock’s paintings. But one thing he remembers about Pollock and that he’s learned from reading about him was his obsessive nature related to his painting. Pollock was absolutely committed to the process of painting. That’s a trait that Donna Isaacs has noticed more in her husband this summer. “Days after the accident, he told me, ‘I’m not ready to die. I have all these paintings to do.'”

He’s been at it since. Barely a day passes when Isaacs isn’t in his studio or painting on site.

Marty Gleason, co-owner of Gleason Fine Art, is curious about whether and how Isaacs’ paintings will change with more time in Portland. Much of his new work involves city scenes, but they are mostly views of the water or distant horizon lines. In subject and composition, they’re not much different from the paintings he makes on Little Cranberry or in Vermont.

“I don’t see Henry as an urban painter at this point of his life. I don’t think you’ll see paintings of the Old Port,” she said. “But I do think he will do more paintings with structures in them.”

Isaacs sells a lot of work because his paintings are happy, Gleason said. Above all, Isaacs is a colorist who fills his paintings with rich, textured bursts of pink, green, yellow and blue. He applies his paint thickly, creating textured surfaces that almost resemble collages.

He infrequently employs the colors of the city, which are darker.

“I think his paintings suggest the feeling of happiness and satisfaction and a joy of living,” she said.

Now more than ever.

Send questions/comments to the editors.