Maine’s highest court has denied convicted killer Dennis Dechaine’s appeal for a new trial, a decision that could shut the door on a 26-year legal saga.

The Maine Supreme Judicial Court released its 42-page decision Tuesday, concluding that any new evidence would not produce a different verdict if a new trial were held.

A Knox County Superior Court judge reached the same conclusion last year, but Dechaine’s attorney, Steven Peterson, appealed to the Supreme Judicial Court, arguing that DNA evidence not presented at the original trial pointed to someone other than Dechaine.

It was the fourth time the state’s highest court has ruled against Dechaine, who may be running out of legal options.

Assistant Attorney General Donald Macomber said Tuesday afternoon that he was “thrilled” with the decision.

“We especially appreciate that the court went out of its way to point out the mountain of evidence against Mr. Dechaine,” he said.

Peterson said he and his client were prepared for the decision and now will decide whether to appeal the case further.

“The court has not been favorable to us, but I think if you tried this case today with all the evidence we have, there would clearly be reasonable doubt,” Peterson said.

Macomber said as far as he’s concerned, Dechaine has no more legal options in Maine. He said Dechaine could appeal to either the 1st Circuit Court of Appeals in Boston or the U.S. Supreme Court.

“If he wants to take this further, we’ll be ready,” Macomber said.

MANY EFFORTS TO FORCE NEW TRIAL

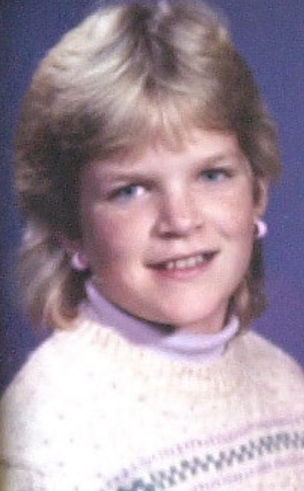

Dechaine, who is serving a life sentence at the Maine State Prison in Warren, was convicted in 1989 of kidnapping, sexually assaulting and murdering 12-year-old Sarah Cherry of Bowdoin in July 1988.

Her body was found in the woods two days after she disappeared while baby-sitting. She had been sexually assaulted with sticks, stabbed multiple times and strangled with a scarf. Her murder remains one of the state’s most notorious homicides.

Dechaine, then a 30-year-old farmer from Bowdoinham, became the sole suspect after significant circumstantial evidence pointed to him.

He stumbled out of the same woods where Cherry’s body was found. His truck was parked nearby. Rope from his truck had been used to bind the girl’s hands. A notebook and a truck repair bill with his name were found in the driveway of the home from which Cherry disappeared.

Dechaine also had a weak alibi. He told police that he spent the day doing drugs and wandering in the woods.

Still, no physical evidence linking the two was found on either Cherry or Dechaine.

Since his original conviction, Dechaine has amassed an army of supporters in Maine and beyond. A group called Trial and Error has raised money for his appeals and DNA testing. A national group called the Innocence Project, which has helped secure many new trials and exonerations for wrongfully convicted prisoners, also backed Dechaine for many years, although the group no longer has his case listed on its docket.

FIRST TEST OF NEW DNA EVIDENCE LAW

Dechaine’s case is noteworthy because it’s the first to go before a judge since the state enacted a law in 2001 that allows prisoners to seek new trials based on DNA evidence.

During oral arguments on the appeal before the Supreme Judicial Court in May, Peterson told justices that DNA found under Cherry’s fingernails belonged to someone other than Dechaine. That alone should be enough for a new trial, Peterson said.

Macomber argued that the DNA evidence was not conclusive and could have been contaminated. He also said all other evidence points to Dechaine, including the fact that he confessed three times and told his original lawyer where the victim’s body was located before it was found.

HARM IN RE-TRIAL? A MOTHER’S PAIN

Hundreds of people have been prosecuted for murder since Dechaine, but none has generated as much interest and scrutiny. Macomber believes that’s because the soft-spoken Dechaine doesn’t fit the typical profile of a murderer and his supporters have been ardent in their belief that he is innocent.

At one point during oral arguments, Justice Andrew Mead asked Macomber what the harm would be in re-trying the case.

Macomber pointed behind him to Cherry’s mother, Debra Crosman, who was seated in the courtroom.

After that hearing, Crosman told reporters, “I hope I die knowing he’s still in prison and will never get out.”

Crosman could not be reached Tuesday for comment. Her daughter would have turned 39 this year.

Send questions/comments to the editors.