For some families, serving in the police or military seems nearly genetic. When generations have served before them, sons and daughters often follow suit. So it should have come as no surprise when acclaimed author Kate Braestrup’s son, Zach, wanted to join the Marines. His dad, after all, had been a state trooper. And therein lies the rub: Braestrup’s life changed forever when her husband, Drew, was killed in the line of duty. In an instant, at the age of 34, Braestrup became a single mother of four pre-teens. So the notion that her first-born son might enlist in the military, at a time of war, carried added weight.

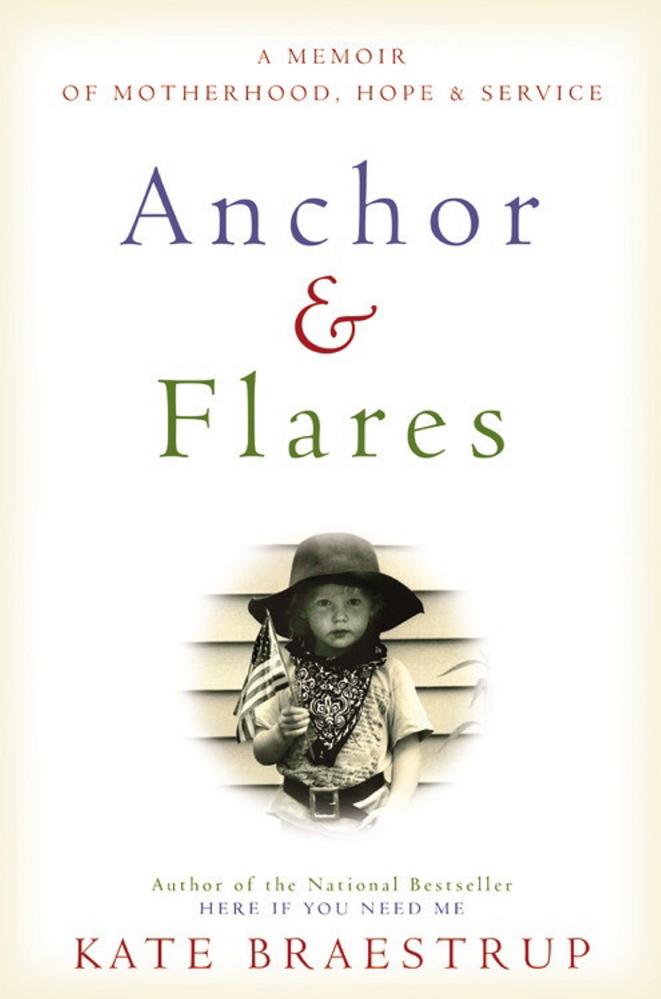

A mother’s inevitable mixed feelings, a collision of fear and pride, form the basis for Braestrup’s new book, “Anchor & Flares: A Memoir of Motherhood, Hope, and Service.” At bottom, it’s a coming-of-age story for both mother and son.

Best-selling author of the memoir, “Here If You Need Me,” Braestrup serves as chaplain for the Maine (Game) Warden Service. She spoke recently from her midcoast home about violence, writing and the meaning of adulthood. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: What was the impetus for your new book?

A: Well, it was a couple of things. Frankly, it was my editor saying, “So, when are you going to write another book?” Then I realized that the biggest change in my life was all the kids getting up and going. That transition was just so startling and more complex than I expected. Everybody knows that teenagers are a pain in the neck. But I hadn’t really heard that having your children become adults was quite so tricky.

Q: Or that adolescence extends well through the twenties.

A: Unless your son joins the Marines!

Zach was our first kid to graduate from high school and leave. If your kid goes to college, there’s this long prodromal period where he’s still kind of half at home, he comes home for holidays and you’re still supporting him. When your kid joins the Marines, the recruiter comes and picks him up, you say goodbye and he’s gone. Not only do you not hear from him for weeks, but he’s earning his own money, he has his own health insurance. He has assumed a lot of the features of adult life.

Q: Enlisting was Zach’s idea. This wasn’t a parent pushing her kid into the military.

A: Certainly not! With great satisfaction, thinking I had made a major breakthrough, I said, “You realize you’re joining the Marines to find your dad, who wore a uniform.” He looked at me and said, “Yeah.” He knew. He was so thoughtful and considered. There was this combination of bewilderment and anxiety – Zach’s going to go to Iraq and get blown up – and a tremendous pride in his taking on adult responsibilities.

As I was writing the book, I realized that I was working toward what it actually means to be an adult. What I arrived at, in the end, is that an adult is the one who serves – the one who becomes the protector, the supporter – and is no longer the one who must be served.

Q: There’s a sense of anxiety that runs through the book. Isn’t worrying the universal job description of mothers, regardless of your kid’s career choice?

A: Right. And it goes on forever as far as I can tell. And love makes you worry. I often find myself in a professional capacity (on a search and rescue mission) talking to people who wonder, “Should I tell my mother that her granddaughter is missing? I don’t want her to worry; she’ll fret.” And I’ll say, “Well, it’s the privilege of love to fret.”

Q: In the book, you talk about the concept of dangerous unselfishness, which originated with Martin Luther King.

A: Basically, it means that to accept your child as an adult is to accept that he’s going to risk himself. That’s very difficult. I go back to Zach being in the Marines or my daughter, Woolie, doing police work. The danger is significant. And it isn’t just the danger of getting hurt. There’s the danger of moral injury – of having to shoot someone. Woolie is putting herself in harm’s way and so was Zach.

Q: You talk about wanting a life of kindness and courage and dangerous unselfishness for your kids. Is there a distinction between dangerous unselfishness and plain old selflessness?

A: There really isn’t. By definition, selflessness is dangerous on some level. It’s pretty hard to think of a job, or role, or action that’s really selfless, that doesn’t involve sacrifice. The more significant the work, the greater the sacrifice.

Q: In your mind, is it any more heroic, for instance, to be a soldier than a nurse?

A: It depends. Zach, as it turned out, was never deployed to a war zone. In fact, the guys that I work with are not fighting people, they’re rescuing people. They also arrest people when they need to, but they aren’t in a war. In our culture, we have trained ourselves to underestimate the way we rely on male violence to protect us.

Q: How so?

A: Most of us get to live our lives not having to even think about using violence because we have 911. And that’s also what we expect of husbands. I mean, if there’s a weird noise downstairs, he’s the one who goes. We take it for granted. We say things about men and male violence without accepting that it’s our violence by proxy.

Q: Part of what you’re describing is violence that is protective, not abusive.

A: Well, yes. But it’s also the idea that it somehow doesn’t belong to us. I remember somebody saying very officiously that the war in Iraq was just about oil. It’s never just about anything. Then I said, “How did you get to church this morning? We all drove. So, if it’s all about oil, it’s all about us. It’s about our ability to do the things we want to do.”

Q: You’ve said that writing is secondary to your work as a chaplain.

A: I love writing. It’s really fun, and it’s very educational. But the chaplain work, and the work with the guys, the wardens, is really crucial. I also think it’s important for me to keep rubbing up against reality in a more direct way. It’s just so easy to get wound into your ideas without ever having to test them.

Q: When you’re called to an accident scene, what is the chaplain’s role?

A: You show up, and you let God figure out what to do with you.

Q: Let’s say you show up, and the person in need is an atheist or agnostic.

A: Oh, that happens all the time. I had a young woman look at me when I showed up. She said, “I’m an atheist and I hate God.” And I just reached up, took off my clerical collar, put it in my pocket and said, okay. So then we go from there. Essentially, so much of what I do has no religious content whatsoever. I’m really just a stop-gap. It’s like being an emergency room doctor – you stabilize and refer. I often tell the wardens that what we’re working with is both the moment and the memory of the moment. The ideal for me is that a family will look back at that moment, which they will remember, and say, “The wardens were great, there was this nice lady and we were powerful. We did a good job.” That they remember their own power, not everybody else’s power – that’s perfect.

Q: What is the most challenging or difficult part of your work as a chaplain?

A: The work itself is very compelling, but there are not enough ladies’ rooms in the Maine woods! I may have to talk to the governor about this.

Joan Silverman writes op-eds, essays and book reviews. Her work has appeared in The Christian Science Monitor, Chicago Tribune and Dallas Morning News.

Send questions/comments to the editors.