In the opening chapter of acclaimed poet Maxine Kumin’s new memoir, we meet the Winokurs, a Jewish family in 1930s Philadelphia. Pete Winokur ran the city’s largest pawnshop at the time, his name a virtual slogan. “Need money? See Pete” read the cover of matchbooks that came with every pack of cigarettes sold back then. In a family anxious to assimilate, young Maxine learned to say simply that her father was a “broker.” She also understood that Yiddish was unacceptable in their household and gesticulating was verboten. “Don’t talk with your hands!” her mother would scold. “You look like an immigrant.”

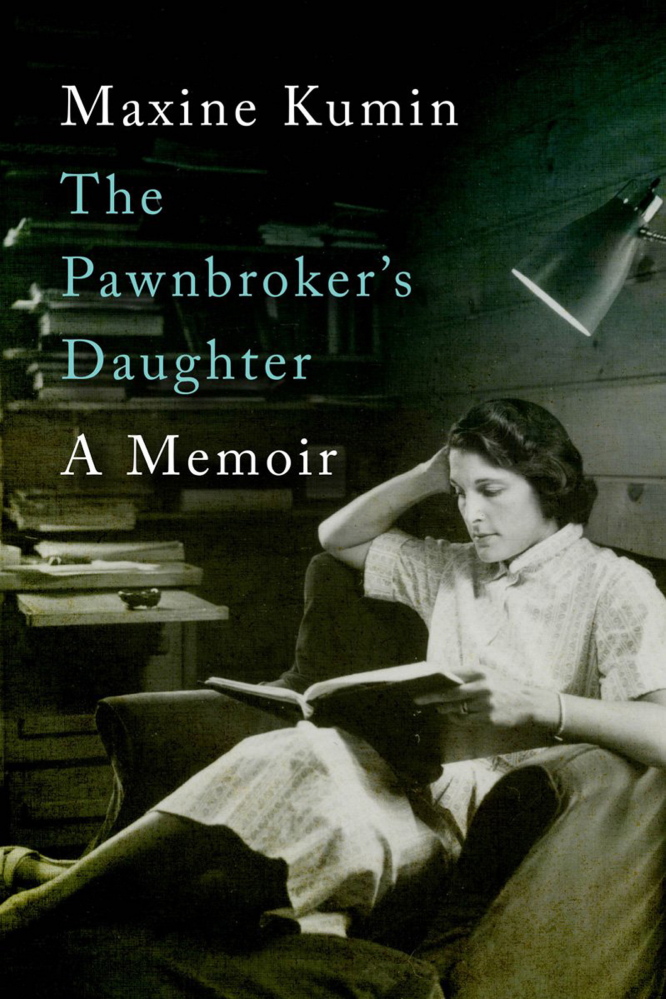

This domestic tableau sets the stage for “The Pawnbroker’s Daughter,” Kumin’s stunning memoir of love and war, poetry, protest and the satisfactions of country life. Kumin is a consummate storyteller. The condensed language of poetry informs her prose, which she layers like well-packed luggage.

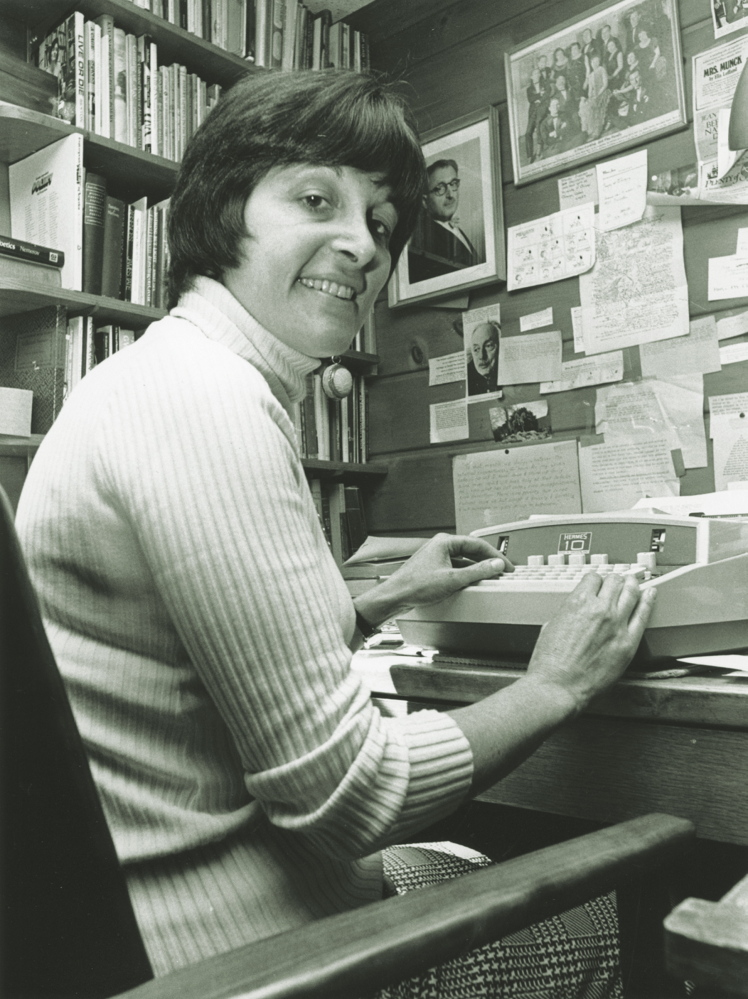

In the course of just five essays, the book serves almost as a time capsule. Kumin, who died last year at the age of 88, lived on the edge of history, both in terms of the indignities she endured and the breadth of her achievements. As a young poet in the 1950s, she wrote light verse that first ran in the Christian Science Monitor, earning five dollars per poem. Later, the Wall Street Journal and Saturday Evening Post came on board, as Kumin gained access to poetry’s largely male domain. Still, as a female of that era, Kumin’s credibility as a poet came into question. Remarkably, her husband had to supply a letter authenticating the origin of her poems.

“In the fifties,” Kumin writes, “women, along with people of color, were still thought to be intellectually inferior, mere appendages in the world of belle lettres.”

Once her poetry gained traction, however, the ironies nearly offset the earlier insult. With the publication of her fourth book of poetry, “Up Country,” in 1973, Kumin won the Pulitzer Prize. Offers of teaching posts, workshops and readings soon followed. Over the years, more poems led to another dozen collections, plus five novels and several books of short stories and essays. Yet in an unlikely turn of events, it was her poetry that helped to support the rural life that Kumin sought.

After years of living in suburban Boston, teaching English composition part time, shuttling her kids to and from lessons and appointments, and frequenting dinner parties, Kumin yearned for a change.

“Even if we had had the income to sustain it, I desperately did not want my mother’s life,” she says. “Nor was I satisfied with my suburban life…. I could have been a case study from Betty Friedan’s ‘The Feminine Mystique.'”

Kumin and her husband, Victor, began hunting for a weekend getaway within a two-hour drive of Boston. When they reached the end of a long dirt road in New Hampshire, with real estate agent in tow, they eyed the ramshackle farmhouse and barn that would become theirs. They bought the former dairy farm where they would later live full time, spending the last four decades of her life raising horses, gardening and adopting rescue dogs.

“After the Pulitzer Prize, I metamorphosed into a recognizable name,” Kumin says. “Suddenly I was in business, the poetry business.” Thus the name “PoBiz Farm” hangs on the barn, symbol of their changed fortunes.

Kumin’s memoir reflects the turbulent times through which she lived, and the subsequent changes in the author’s life and writing. Her poetry grew in scope, tackling both political issues and the bucolic themes for which she became known. Most readers will likely come to this book curious about the life and legacy of a pioneering modern poet. Yet even newcomers to Kumin’s work will find here a great story, a major chunk of mid-20th century American history and the woman herself, who lived an extraordinary life.

Joan Silverman writes op-eds, essays and book reviews. Her work has appeared in The Christian Science Monitor, Chicago Tribune and Dallas Morning News.

Send questions/comments to the editors.