When Apple introduced its new streaming music service at its annual developers conference last month in San Francisco, the tech company made sure to have the rapper Drake on hand to lend the announcement a bit of sizzle. But Drake wasn’t the star of Apple’s presentation, which focused on Jimmy Iovine and Eddy Cue, two of the many executives who have stepped into the spotlight as the record industry struggles to remake itself for the digital age.

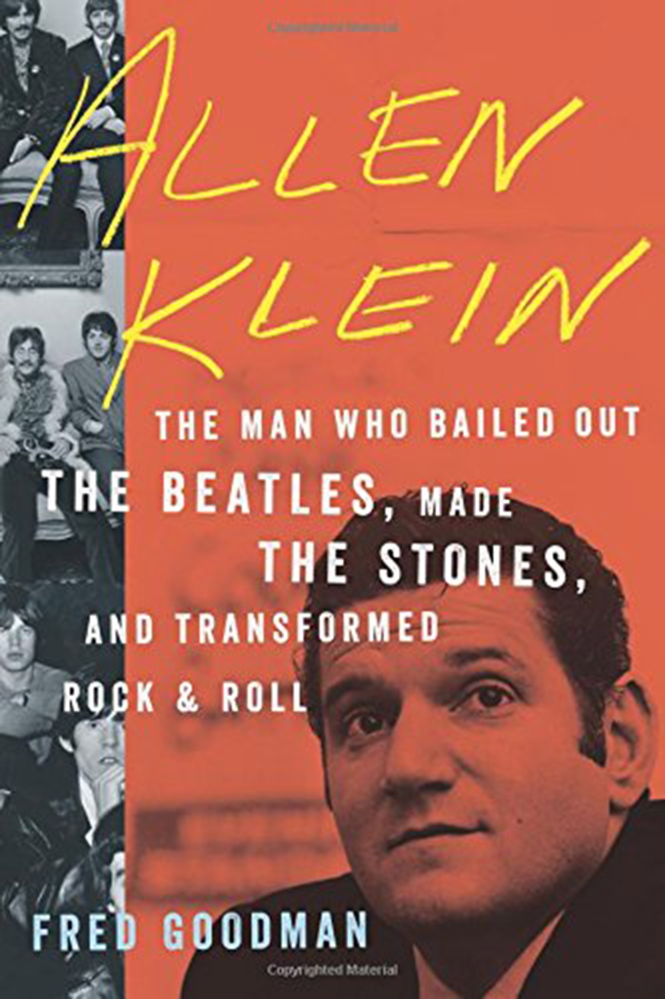

Today such visible string-pullers – think also of Justin Bieber’s manager, Scooter Braun, or Spotify chief executive Daniel Ek – wheel and deal before a public that’s been trained (in large part by the spread of consumer-media box-office reporting) to regard itself as a kind of amateur pundit class. Yet it wasn’t always thus, as the veteran music journalist Fred Goodman reminds us in “Allen Klein: The Man Who Bailed Out the Beatles, Made the Stones, and Transformed Rock & Roll.”

A rough-edged but charismatic player who at one point managed both the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, Klein worked in shadows that are hard to imagine now, when Taylor Swift’s feud with Ek over what Spotify pays artists makes it to the cover of Time magazine. Fifty years ago, what happened behind the scenes generally stayed behind the scenes, and that lack of transparency, Goodman argues, might have enabled the creative accounting that in some cases left Klein making more money than his clients.

This isn’t to say that Klein, who died in 2009, lacked an appetite for recognition – or that Goodman lacks sympathy for his subject. The author, a former Rolling Stone editor whose previous books include “Fortune’s Fool: Edgar Bronfman Jr., Warner Music, and an Industry in Crisis” and “The Mansion on the Hill: Dylan, Young, Geffen, Springsteen and the Head-On Collision of Rock and Commerce,” roots his story in Klein’s grim upbringing in Depression-era New Jersey. (His mother died when he was less than a year old, and his father sent him to live in an orphanage at age 4.) For Klein, Goodman writes, success “came down to having the things he’d missed as a child: companionship, a sense of worth, and power over his own life.”

That power derived from an aha moment in which Klein, working as an accountant in the late 1950s for a firm representing music publishers, realized that performers were likely getting stiffed by record labels as a matter of course. Before long he was promising name-brand artists that by auditing the labels he could find them money they were owed – and he was delivering. Soul singer Sam Cooke was so impressed that he hired Klein to oversee all of his affairs; the manager, known for his combative negotiating style, struck an unusually lucrative deal with Cooke’s label that attracted the interest of even higher-profile acts, including the Stones.

“As far as Allen was concerned, the business had it backward,” Goodman writes, laying out the basis of the transformation to which he refers in his book’s subtitle. “It wasn’t the [record] companies that were irreplaceable; it was the people who made the records.”

Klein’s belief in his clients led to ever bigger paydays, not just for the artists but also for Klein himself. He devised complex corporate structures to conceal how much income he was taking. Though Goodman provides plenty of detail here – more, in fact, than we can probably use, as when he goes into British tax law’s treatment of capital gains – he keeps the story moving briskly, peppering the money talk with colorful backstage anecdotes and sharp analysis of the rock ‘n’ roll image factory then revving into full gear. The bad boy Stones, he sniffs, were in reality “about as dangerous as Coca-Cola and just as eager to be sold.”

Yet “Allen Klein,” which draws on previously unpublished interviews Klein conducted with the writer and MTV executive Bill Flanagan, slows down considerably when it reaches the manager’s late-1960s recruitment by the soon-to-split Beatles. Perhaps that’s because Klein had so much to say about the band, whose business was the “white whale” he’d been working his entire career to capture. Whatever the reason, Goodman’s blow-by-blow account of the Beatles’ breakup – and the meticulous financial untangling it necessitated – is a long and winding slog.

Fortunately, his writing picks up for the final stretch of his book, which charts the strange turns Klein’s career took in the 1970s, including his collaboration with the surrealist filmmaker Alejandro Jodorowsky and the two months he spent in jail after being convicted of tax evasion. And Goodman also channels Klein’s glee over the emergence of the compact disc and the incentive it offered fans to repurchase old music he controlled.

Reading about that, it’s easy to wonder what Klein might have made of the now-ascendant streaming model, in which artists are paid even less for their work than they were in the bad old days.

You can bet Eddy Cue is happy not to know.

Send questions/comments to the editors.