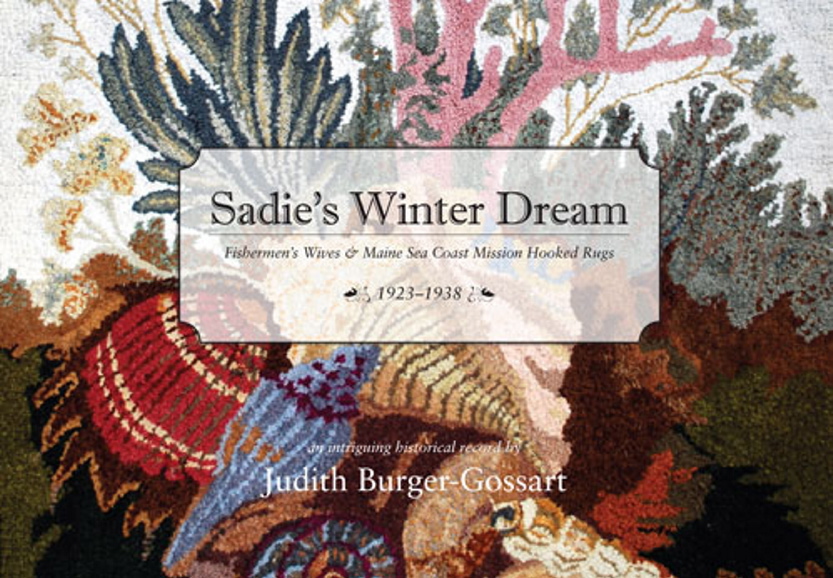

This new book by nationally known magazine writer, rug maker and designer Judith Burger-Gossart of Salisbury Cove on Mount Desert Island should not be overlooked. “Sadie’s Winter Dream: Fishermen’s Wives & Maine Sea Coast Mission Hooked Rugs” is a handsome book containing good insight into state social history and the development of crafts.

This is not the first volume to discuss the subject. Mildred Cole Peladeau did a first-rate job in her excellent book, “Rug Hooking In Maine, 1838-1940,” published in 2008. Both Peladeau and Burger-Gossart point out that non-woven rugs have been included in Maine art catalogs from the beginning.

In 1838, the Maine Charitable Mechanic Exhibition offered the first showing of the hooked rug as a craft in America and took place in the flourishing greater Portland area, where men and women had security and time on their hands.

Burger-Gossart takes the reader nearly a century forward to the struggling Maine outposts of South Gouldsboro, Frenchboro, McKinley (Bernard), Little Deer Isle and Matinicus, setting the tone starkly.

“While in cities like New York, the Jazz Age was in full swing with prosperity on the rise; it was a far different story in Downeast Maine. Life was harsh, poverty endemic; there was little jazz and no safety net,” she wrote. “Fishermen lived on islands or coastal communities that were isolated unto themselves. A Grange, a church, or a small sewing circle was the center of the community. Hard work the norm. Life was raw, never rest the motto.”

In a sense, this was as much an outsider’s view, as anything.

The Maine Sea Coast Mission was founded in 1905 by two missionary brothers from Prince Edward Island who viewed the coast of Maine as a sort of wasteland of Zion, ill health and semi-civilization. Sometimes the locals were willing to receive assistance. Other times they saw missionaries as “snoops.”

In the early 1920s, public school teacher Alice Moore of Rockland married Captain Jerome Peasley, keeper of the Hancock Point lighthouse, with whom she raised two children. Alice separated from Peasley about the time she headed up the mission’s new hooked rug department.

Alice Peasley emerges as a standout figure in the development of Maine crafts. The idea of having women make rugs had its roots in the world Arts and Crafts movement and came directly from the Grenfell Mission in Newfoundland and the Maritimes. The Grenfell rugs used professional designers and were made by locals and sold at a good mainland price.

The Maine Sea Coast Mission could not afford uniform templates. Thus, the rugs it produced were the personal and sometimes unique visions of local women and a few men.

The book’s title and cover celebrate rug hooker Sadie Lunt (1877-1962) of Frenchboro, whose “Still Life Tropical Marine” is termed “an extraordinary example of how the crafters’ skills and sophistication grew over the years.” One can argue against artistic insight, since it was based on a chromolithograph, but the author notes, “Sadie has taken a dark, rather sinister print and transformed the image into a lovely warm delight. During a cold Maine winter she was clearly thinking tropical.”

Indeed, some of the craftswomen wrote about seeing nature in transforming ways, and they certainly produced arresting works. This was one of the mission’s goals, of course, but there is a persistent thee and thou attitude, with Peasley stating, “Our people are conservative New England folk. They do not take kindly to changes. They are not schooled in self-expression. They distrust their own mental process.”

Money was a major incentive for “our people,” with income from the rugs often paying off mortgages or providing food for the table.

As one of the women stated, “I never thought I’d live to see the day when I could do something somebody else would want and value.”

William David Barry is a local historian who has authored or co-authored seven books, including “Maine: The Wilder Side of New England” and “Deering: A Social and Architectural History.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.