WISCASSET — This week marks the beginning of sleepaway camp season as lucky children “from away” arrive by bus, car, planes and trains to be immersed in Maine life on and in lakes, rivers, mountains and the coast; it’s been an American tradition for well over a century. While many Maine summer camps came and went between the late 19th century and the 1940s, others – like Winona in Bridgton and Wyonegonic in Denmark – stayed open through both World Wars, the tumult of the 1970s and more than one recession. Camp Arcadia in Casco is celebrating its 100th year this summer. Their endurance may be a testament to the principle of Maine as Vacationland, as well as the willingess of camp owners to weather tough times and parents to pay steep fees for seven weeks in the Maine sun (and rain).

But one Maine summer camp, Chewonki, also celebrating its 100th anniversary, has endured by evolving into a model of sustainability, and not just in the summer months; this environmental education foundation runs year-round.

Its many programs include a junior semester for high school students from all over the world, nature education for students from other Maine schools, and wilderness adventures in the wilds of Maine, whether the Allagash or the sturdy flanks of Mount Katahdin.

To understand how Wiscasset’s Chewonki has become the sustainable champ of camps, drop by in February to see the smorgasbord of Chewonki’s renewable energy systems humming away. An extraordinarily efficient wood-burning furnace heats two of the main buildings. Another building runs on geothermal power. There are solar panels on a cabin named for longtime trustee Gordy Hall, who came to Chewonki as a counselor in the 1940s. Solar energy warms the water for showers and powers the electric car-charging station. A wind turbine contributes to the grid and as backup, a hydrogen system can provide electricity.

Don’t neglect the students chopping wood in the forest. It’s way below freezing, and the snow is deep enough to make a long-legged, hairy Belgian draft horse more than a little grouchy. Sal the horse has spent her morning up to her belly in snow “twitching” felled logs (pulling them out via chain) from a densely wooded area in Chewonki’s 150-acre forest. She’s snorted her displeasure. She’s also (briefly) dragged farm manager Megan Phillips on her belly across the snow, to a chorus of deepening “whoas.”

The students, who attend Chewonki Semester School, are chopping wood much more enthusiastically than Sal is twitching it. For them, it’s one of the many exercises in self-sufficiency that comprise the Chewonki experience – replenishing the wood supply so that the next semester’s students, and the summer campers as well, can power the stoves in their cabins on damp and chilly days. Sal will pull most of those logs out of the wood.

“You’re seeing all of her tricks,” Phillips said ruefully, after she’d recovered her breath. Chewonki has had a organic farm on the peninsula since 1981, and a horse is crucial to its operations. “Sal doesn’t have a key that you turn on and off,” Phillips continued.

Phillips is tall and striking and bathed in warm farm smells. Call her a Norse goddess or an Amazon; both labels suit. Though the horse belongs to Chewonki, technically, Phillips explains, “She’s nobody’s horse.”

Sal, Phillips said, is emblematic of Chewonki, a place that requires teamwork to sustain itself while honoring individuality, and where ownership is a fluid term, whether applied to a camp bed or a horse.

Last year, Sal accidentally stepped on Phillip’s leg, tearing a ligament. During a month of rest, Phillips read up on horse psychology and did a lot of contemplation around the matter of Sal. As the horse and her not-owner stood on the snowy road, the harness firmly in Phillips’ hands, Phillips recounted how she walked into the barn after that month away and posed a question to Sal: “Can we be on the same team?”

It’s a very Chewonki question. And the answer? Almost always yes.

IN THE BEGINNING

A mile-long tunnel of woods welcomes the visitor onto Chewonki Neck. Every camper, student and counselor comes to their Chewonki experience on this road. And in 1918, this was the approximate route traveled by Clarence Allen, hoofing it down the neck via snowshoe to scout the land. He was a young schoolteacher from The Rivers School in Massachusetts who had started a boys camp in upstate New York three years earlier. But when he saw this pristine peninsula, he made the decision to relocate. The price for the 125-acre parcel he bought was $2,500.

Allen was a passionate advocate for a practical outdoors education, a believer that competition was less important than teamwork and time in nature. Over the years, he brought people into the Chewonki fold who would change it and push it forward, starting with Roger Tory Peterson, the author of the seminal birding guide, “Field Guide to Birds.” Peterson was 22 and already a bird expert when he arrived to be the nature counselor at Chewonki in 1930. He didn’t teach so much as demonstrate, according to Chewonki legend (many such legends incorporated in a new book “Chewonki: 100 Years of Learning Outdoors”) and the children followed him around, chasing and identifying birds alongside him. He returned for three summers and in 1934 published a guide that was the unchallenged Bible of birders for a good 70 years. “The Field Guide” was dedicated to two men, one of them Clarence Allen.

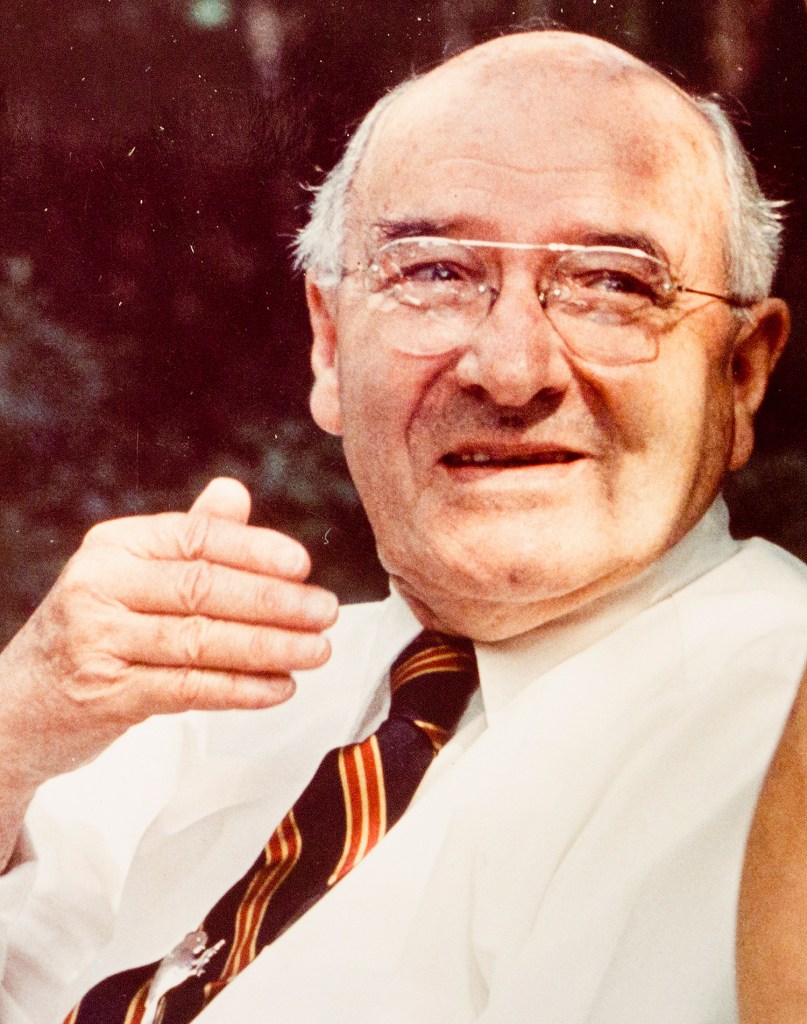

By all accounts, Allen had an eye for the kind of outdoors type who could make a contribution to Chewonki while getting as much as they gave. He recruited a recent graduate from The Rivers School, Gordon (Gordy) Hall in 1949. Hall was an Amherst student who had caught Allen’s attention by canoeing down the Allagash at age 16. “In those days it was akin to going to the North Pole,” Hall said. Allen wanted to start sending his campers farther afield on adventures, and he recruited Hall to lead them.

That first trip included about ten 13-year old boys – one the future Chewonki executive director Tim Ellis – all bouncing around in the open back of a farm truck. They climbed Katahdin, fished in Baxter State Park, and came back happy and content. So did Hall, who would remain a lifelong supporter of the place that had served him so well. “It was a bit of a joke that the Chewonki counselors had a better time than the kids did,” Hall said. He’s 84 and still on the board of advisors.

Those kind of trips are now a regular part of the Chewonki experience. Brunswick native Gemma Laurence’s introduction to Chewonki was on a wilderness trip to the Allagash the summer after ninth grade. Three weeks, no mosquito repellent, a pack of teenagers cooking all their own meals and carrying their canoes between waterways. “After I finished, I felt so much stronger, mentally and physically, knowing that I could carry a canoe on my back with my friends for three miles straight,” Laurence said. In 11th grade she left Waynflete for Chewonki’s Semester School, where she found herself wielding an ax in the woods with Phillips’ woodlot team, “something I’d never done before and never thought I’d do.”

Chewonki instilled in her the desire to become involved in Waynflete’s Environmental Action Group and to include environmental sciences among her classes when she matriculates at Middlebury next February. During her gap semester, she plans to travel to France and New Zealand to do stints on organic farms. She described all this on a phone call from a car headed north on Route 1; her parents were driving her to Chewonki to start her first summer as a counselor.

Laurence represents what Gordy Hall calls Chewonki’s best ambassadors. “Because they are old enough to learn and they are idealistic enough to take it all very seriously and understand what is going on,” he said. They’ll make efforts to improve the world “instead of plunging in the world of material destruction.” He paused. “I sound like a zealot,” he added. “And I am a zealot, but what is happening is true.”

Chewonki alumni include the children of movie stars and rock stars; no one denies that for the first half of its 100-year existence, it was a camp mostly for children of privilege. But many of those children have pursued careers in environmental education or advocacy, including James Balog, whose photographic survey of glaciers was featured in the documentary “Chasing Ice,” and Will Bates, a co-founder (with author Bill McKibben) of 350.org, an organization working to solve climate change.

PRACTICING WHAT THEY PREACH

The renewable energy systems were practical adaptations as the campus began to transition in the 1970s and ’80s from simple summer camp to year-round school. But they also serve as models for all the different, gentler ways humans can live on the land and not just in the season of tents and long warm nights.

It was Tim Ellis who led that transition. His father had, like Allen, been a teacher at the Rivers School and a summer Chewonki stalwart, and the young Tim Ellis never knew a time when he wasn’t spending summers at Chewonki. In the mid-’60s, he was living in Europe and teaching at an international school when he got a call from Allen asking him to take over leadership of the camp. Chewonki had become a nonprofit in 1962, a crucial decision toward its evolving future. For a few years, Ellis divided his time, summers in Maine, academic years abroad. Then he decided summers weren’t enough.

“I had become convinced that we were doing more in the way of character development for young people at Chewonki in the summer than I was doing in a whole school year,” he said. “And that there must be a way that we can extend the good things that we’re doing at Chewonki.” Meanwhile, as he pointed out, “There was a 400-acre peninsula on the coast of Maine sitting idle for nine months of the year.”

They tinkered, adding boat-building programs, semesters for college students (in conjunction with the College of the Atlantic). A program called Maine Reach began in 1973 and focused on Maine as a classroom. It then evolved into the Semester School, which in turn owes much to Vermont’s Mountain School. If a program wasn’t sustainable, they cut it. “There were a lot of good things that came and went,” Ellis said. A spirit of frugality prevailed, and that included incorporating students into building projects, from boats to new classrooms. “Always,” Ellis said. “Everywhere somebody looks at Chewonki, they can find something that was contributed or made by a participant.”

That spirit continues today. Have lunch with the staff in the dining room, where beet cupcakes are embraced by all and the milk and cheese comes straight from Phillips’ farm operation, and you’ll see Ann Carson, the head of the Semester School, push back from the table and head off for dish duty. No one is exempt and no one seems to mind, whether they are processing chickens or castrating spring lambs.

NO CORNERS TO HIDE IN

Although Chewonki has expanded its programs and land holdings (1,200 acres around the state), one thing it hasn’t done is ramp up enrollment to offset costs, including those of supporting a considerable staff. In 1946, a staff of 38 oversaw 67 summer campers. Today, two summer sessions average 150 campers each, with a staff of close to 50 counselors. Logistically, it might work to throw up a few more cabins and bring in a few more students, but don’t raise the question to Chewonki’s leaders, past and present.

“You shouldn’t mention it even,” said trustee Gordon Hall. “Really, it is profanity.”

Ellis said Chewonki “needs to remain small for every student to feel a sense of ownership.”

“There aren’t any corners to hide in,” Ellis continued. “Everybody has to be a doer.”

That’s the way the “magic” works, he said.

When author and college professor Jaed Coffin was admitted to Chewonki’s Semester School as a scholarship student in 1996, his Thai mother, who had raised her children as a single mother in Brunswick, proudly taped his offer letter to the refrigerator, with the relatively small amount she had to come up with circled in red. “She was really proud that I had gotten that kind of scholarship,” Coffin remembered. “And that I was worth it to them.”

He was less certain. “I really had some hangups about going to school with some very wealthy folks,” he said.

They dissipated quickly on Chewonki Neck, where Coffin said his class quickly became a cohesive team. That’s typical, he said, as if “everyone is dating each other in these perfect platonic relationships.”

And it turned out that the children of privilege were entering his world in a leveling way. “It was the kind of place where it was cool to be kind of like a Maine kid,” Coffin said. And Chewonki taught him things he’d never known about his world. Like 70 kinds of birds, songs included. He came into Semester School able to identify only a robin and a chickadee. “They drill you. Every week there is a bird test.” Chewonki continues to enrich his relationship with Maine; this past winter he took his daughter to one of Chewonki’s Traveling Natural History programs, which brings live animals to schools, libraries, campgrounds and resorts. She was captivated by a rehabilitated snowy owl, one of those original 70. “I felt so honored that I knew something about those birds,” he said.

THE NEXT 100

The summer at Chewonki will be a celebratory one, culminating in a reunion and party in August on Chewonki Neck. But as it moves into its next century, Chewonki hopes to evolve still more, into an even more active participant in the lives of Maine public school students. Since 2011, Chewonki has been successfully seeking grants to bring hands-on science learning to schools in Wiscasset and Bath.

And it’s not just visits to classrooms. Regional School Unit (RSU) 1 teacher Lawrence Kovacs helped develop a program to take eighth graders on a weeklong canoe trip in conjunction with Chewonki Outdoor Classroom instructors. The program, FLOW (Fundamental Learning on Water) is funded by the school district, Chewonki and local institutions, including Bath Savings Bank. These were kids for whom the Chewonki experience seemed out of the question financially. The response was overwhelming positive, and the hope is to continue it.

“Lawrence came to us and he shaped something with us,” said Willard Morgan, the current president of Chewonki. “Now we want to keep building that model deeper.”

SUSTAINING MAINE

For most Mainers, going to sleepaway camp was for other kids, kids from away. If you lived here, your Maine experience was special in its own, self-serve way. If you left the state, you were likely to encounter children of privilege who told you how they’d gone to summer camp in your state, and how neat it was. Maybe they even went to Chewonki. Morgan wants to sustain Chewonki by sustaining Maine’s children, bringing the Chewonki curriculum and spirit to K-12.

“We see our future bound up in the future of our local communities,” Morgan said. “We don’t see a healthy Chewonki unless we have healthy schools and healthy communities around us.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.