Fifty years ago, they came to an off-the-beaten-path mill town called Lewiston looking to settle a score during unsettled times, two unpopular boxers staging a fight that other cities were afraid to host.

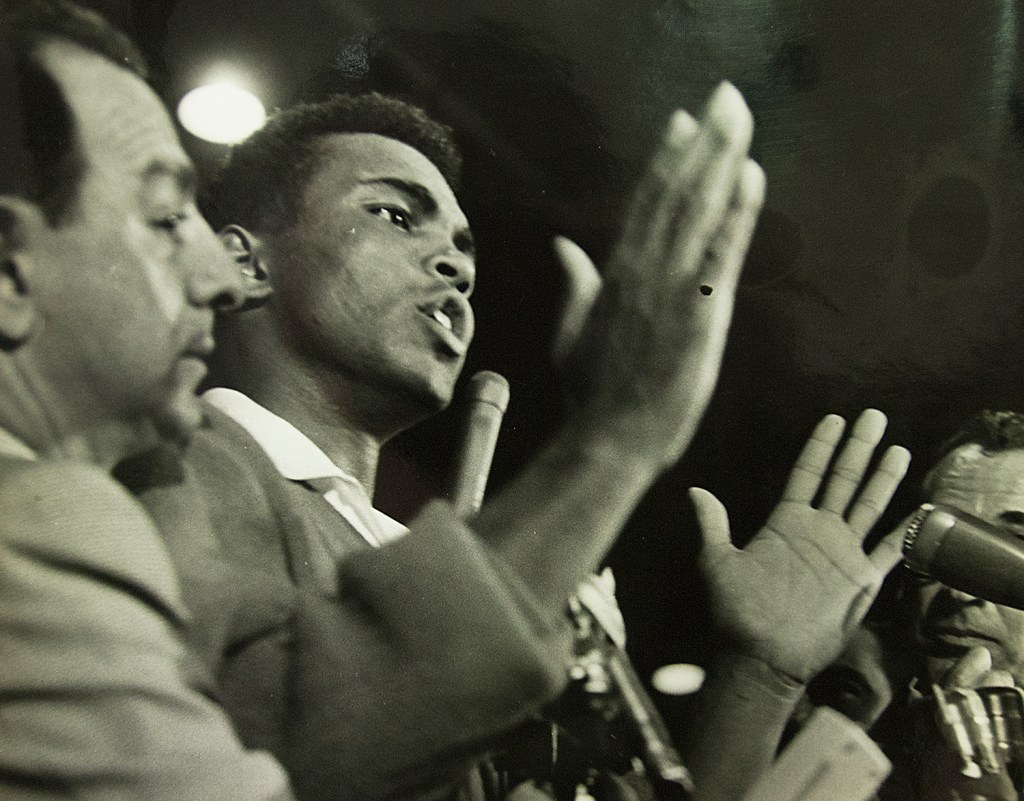

Muhammad Ali was the new heavyweight champion with the new name that mainstream America wasn’t ready to acknowledge, a mouthy 23-year-old many wanted to see humbled.

Sonny Liston was the illiterate ex-con of unknown age, a brawler viewed as brooding and brutish and a relic of a bygone era in boxing when the mob was in control.

Ali, then Cassius Clay, had taken Liston’s title in February 1964 when the champion, complaining of a sore shoulder, refused to get up from his stool for the seventh round.

When the long-delayed rematch finally arrived, only 2,434 people paid their way into a hockey rink on Birch Street that somehow had become the center of the sporting world. What they witnessed is still in dispute. Less than two minutes into the fight, Liston was on the canvas and Ali was strutting in victory after a right-handed blow that almost no one saw land.

Pristine punch? Poorly disguised dive? The debate continues.

It is a single photo that has brought clarity to the events of May 25, 1965. If you look closely, it reveals everything that was to come.

Ali roars triumphantly as if to announce himself to a world he would eventually conquer. Liston, flat on his back, stares at a life about to devolve into ridicule and an undignified death.

“Ali-Liston is an interesting fight because there’s no good guy, there’s no protagonist. Liston never understood why people hated him so much. Ali is seen as box-office kryptonite after he declares himself a member of the Nation of Islam,” said Michael Ezra, a professor of American multicultural studies at Sonoma State University in California and author of “Muhammad Ali: The Making of an Icon.”

“Ali also defied the conventions of masculinity at the time. He had a high voice, called himself pretty, had no body hair, danced around the ring, didn’t seem willing to put it on the line. There were whispers that Ali was gay, at the very least unmanly.

“That started to change. There would be no Ali without those Liston fights. He never would have gotten another title fight if he hadn’t won in Lewiston.”

• • • • •

The rematch was scheduled for Nov. 16, 1964, at Boston Garden. But it was clouded from the beginning. The World Boxing Association, upset that the fighters had agreed to a second bout before the first even occurred, balked at recognizing Ali as its champion. The sanctioning body was also upset when Ali joined the “Black Muslims” shortly after his win in Miami and changed his name, first to Cassius X, then to Ali.

“Clay has proven himself by his personal action as a detriment to the boxing world and had set a poor example for the youth of the world,” WBA President Ed Lassman complained.

While that simmered, Ali had to pull out of the fight after contracting a hernia, and it was postponed by six months, still intended to be held in Boston.

By the time spring rolled around, local District Attorney Garrett Byrne was seeking to block the fight because the promoter, Inter-Continental, didn’t have a license to operate in Massachusetts. Many felt the real reason was fears over violence aimed at Ali in the wake of the assassination of Malcolm X in February. It didn’t help that Liston had been arrested, for the 20th time, for speeding and carrying a concealed weapon shortly after the first fight with Ali.

Word got out that the Boston match was in peril, and promoter Sam Silverman was looking for a city willing to incur the wrath of the WBA, which ruled the sport in 47 states, including Maine. The boxing association was claiming that Ernie Terrell should be declared the real heavyweight champion. Cleveland declined; Pittsburgh bowed out; Houston was briefly in the running, but the Astros didn’t want to give up a home baseball game against the Reds that night.

The May 25 date had to be preserved because of the windfall anticipated from closed-circuit television rights. Projections were that 630,000 seats would be sold at 400 outlets in 21 countries, at $6 apiece, for earnings of $3.78 million. That was the big money. How many people showed up in person, if any, would be a small bonus.

Sam Michael, then Lewiston’s economic development director and a local boxing promoter, sensed an opening, and suggested to Silverman that he bring the fight a few hours north. On May 7, that’s exactly what happened, a sudden and shocking announcement that left the people in Lewiston amazed and giddy. The heavyweight championship, an event akin to the Super Bowl in those days, was coming to their town.

The site was to be the Central Maine Youth Center, commonly known as St. Dominic’s Arena and now called the Colisee. The shed-like structure had been built in 1958 to host local hockey games. But it was big enough in a pinch. The Dominican Fathers normally rented it for $250 a day; they quickly accepted $2,500 to let the boxers have it for an evening.

“(Boston) politicians were giving (the fight) flak. For all I know Silverman wouldn’t give them a bribe,” joked Michael’s son, John, now 64. “He called to see if there was a place to house the 400 media members. My dad said, ‘Sure, the Poland Spring House.’ That was the answer they needed. They had to preserve the (TV) tickets already sold. It had already been delayed once. They figured, if we had to cancel this thing again, we were toast.”

The fight became the talk of the state. Michael spoke confidently of a sellout at the arena, whose listed capacity kept mysteriously increasing in newspaper accounts – from 5,200 to 5,500 and finally 5,900. Tickets were priced at $25, $50 and a garish $100 for ringside seats ($752.60 in today’s dollars). The “cheap” seats sold out quickly; not so the rest. The eventual crowd was the smallest to witness a heavyweight title fight in modern times.

Ali kept training in Chicopee, Massachusetts, meaning it was up to a reluctant Liston to decamp to the Poland Spring House, where he soon settled into a genteel routine of horseback rides, salmon fishing and sparring sessions attended by hundreds of gaping locals.

Things were less tranquil at the Ali camp, where the champ had to squelch rumors that armed Nation of Islam assassins were en route from New York. He couldn’t convince the overwhelmingly white press to use his new name. Newspapers still referred to him as Clay. Occasionally, they would add “Muhammad Ali” in parentheses, but even then could never agree how to spell it. Mohammed, Muhammid, Muhammud were among the variations.

Ali didn’t transition to Maine until May 23, the Sunday before the fight. With him came some of the same hysteria that had descended on Massachusetts. His life was insured for $1 million, and that was just that he would make it through the next few days. His mother, Odessa, famously declared that she was more afraid of what the Black Muslims were doing to her son than any threat Liston posed. Security guards for the fight numbered 200, bolstering a Lewiston police force that only mustered 72 at the time. Fans entering the arena were searched, long before that became the norm at big sporting events.

“I think that everybody feared the Muslims. Because Ali coming in, that was his new religion,” recalled Joe Gamache Sr., then a 27-year-old avid fight fan and resident of Lewiston. “Come to find out all it was was nothing but a religion. But you thought everybody had guns and all that.”

Fight time, scheduled for 10:30 p.m., arrived without incident. Liston, who had been a 7-to-1 favorite to beat Ali in their first meeting, entered the ring still as the odds-makers’ choice, but at only 13-to-10.

It was a reflection of how well-regarded Liston was at the time, and how many skeptics remained about this kid calling himself Ali. Liston had 15½-inch fists, the largest of any heavyweight champion (Ali’s measured 13 inches). He had a remarkable 84-inch reach despite being only 6-foot-1 (Ali, at 6-2½, had a 79-inch reach). Liston had dismantled Floyd Patterson twice with first-round knockouts en route to the title. He was still seen as the more formidable boxer.

“The guy was a well-rounded fighter, and he was so technically sound that all his shots were like thunderbolts,” said Michael Bentt, a former heavyweight champion who became an actor and portrayed Liston in the 2001 biopic “Ali” starring Will Smith. “He was probably in the top two of all-time boxing greats, behind Jack Johnson. In their prime, Sonny Liston knocks out Joe Louis.

“But Ali had the skills of a featherweight at 200 pounds. He had the gift of awkward craft, where Sonny had conventional craft. To me, Muhammad Ali redefined boxing. That fight (in Lewiston) cemented his stature in the world of icons.”

• • • • •

It took time for the adulation to come to Ali. In the immediate aftermath of the murky circumstances surrounding his knockout of Liston, there were cries of a fixed fight. It is still known as the “Phantom Punch” and pundits at the time complained of “the pain in Maine.”

A mere 90 seconds into the fight, Liston, who was having trouble catching up with the faster Ali, threw one in a series of ineffectual left jabs. Ali countered with a quick right hand that sent Liston down on his back. Ali, appearing surprised, then angry, bellowed at Liston to get up and fight, before skipping around the ring in triumph while referee Jersey Joe Walcott tried in vain to coax him into a neutral corner.

Walcott then left the still-supine Liston to consult with the ringside timekeeper, Francis McDonough, never officially starting a count that could have declared the fight over. Liston got back up and the fight briefly resumed, with Ali chasing Liston into the ropes. Nat Fleishcher, editor of The Ring magazine, waved to Walcott saying the count had reached 12 seconds and that the match should have ended. Walcott then broke up the fighters and declared Ali the winner as the crowd sat in stunned silence before howling in disbelief. Elapsed time was 2 minutes, 12 seconds.

Ali, always insisting that the knockout blow was perfectly timed and placed, then mowed through the heavyweight ranks, taking down Patterson in November 1965 and vanquishing a remarkable five contenders the following year. In 1967, Terrell finally got his shot and lost a unanimous decision at the Houston Astrodome. After Ali knocked out Zora Folley on March 22, 1967, his reign abruptly ended over his continued refusal to serve in the Vietnam War. Ali cited religious reasons and his quote – “I ain’t got no quarrel with those Vietcong” – became legendary.

For 3½ years, as his case was appealed, Ali’s stance cost him untold millions but won him a legion of admirers, particularly among young people.

Ali became a symbol of both the civil rights and anti-war movements, uniquely bridging the two dominant themes of that turbulent time in American history. He started speaking on college campuses, learning to hone his message to please mostly white crowds.

“The first speeches he did, he was all Nation of Islam, he was puritanical, he would chastise people for smoking marijuana, he thought hippies were the unwashed,” Ezra said. “He does have a strong black nationalist streak. Ali did warm up to his white college idolaters. He realized that was an important part of his base. And they always loved him.”

People coming of age in the 1960s gravitated to him, like Bobby Russo of Portland, who attended the Lewiston fight at age 9. His father, he said, was no fan of Ali, a common generational split.

“There was a groundswell of opposition to him. And then he became the icon of that era, the real trend-setter,” said Russo, president of the Portland Boxing Club. “He had a lot of guts because he could have done the easy route, go around and shake hands with people. That’s what they wanted him to do, basically. He said, ‘I’m not doing that. I don’t care what you do.’ ”

When Ali finally returned to the ring, in October 1970, he put together a decade of pugilistic dominance and international acclaim that the world had never seen before or has ever seen since. He toured Africa and Asia, drawing big crowds. He brought two of the most memorable fights in history to those continents, an unprecedented action. He beat Jerry Quarry in his initial fight, but lost for the first time the next year, in a 15-round classic to Joe Frazier. In 1973, he came up short in a split decision against Ken Norton, but turned the tables on him six months later. He gained revenge on Frazier the following year, handed Liston protege George Foreman his first defeat in the fabled “Rumble in the Jungle” in the Congo late in 1974, then outwilled Frazier one more time in 1975’s grueling “Thrilla in Manila.”

The introduction of closed-circuit TV – the fight in Lewiston was the first major U.S. sporting event to be seen live in Europe – spurred his rise in popularity. It was the forerunner of pay-per-view, and meant that Ali’s fights could be beamed around the world, even behind the Iron Curtain.

“That’s something that really made Ali bigger than life,” said Al Valenti of Portland, whose family has been involved in staging boxing matches for three generations. “Because if only domestic television sets had it, who are you?”

By the time his boxing career ended in 1981, with losses in three of his final four fights to finish 56-5, Ali had done the unthinkable – earned unanimous acclaim from boxing’s hard-to-impress observers as the greatest heavyweight ever.

“Ali changed boxing,” said Thomas Hauser, author of the award-winning 1991 biography “Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times.” “If Ali had been a boxer cut from the mold of Joe Louis, people would have said, ‘OK, we have a new champion.’ Ali pushed boxing off of the sports pages and onto the front pages.

“I don’t think there’s ever been a figure like Ali. He’s one of a kind.”

• • • • •

For Liston, there was only torment after he left Lewiston in disgrace, insisting he never took a dive and that he could have fought on if Walcott hadn’t stopped the fight.

Fleeing to Sweden, he won four fights in 1966 and ’67, none lasting more than seven rounds. He returned to the U.S. and blasted a series of forgettable opponents. He got one more shot at a quasi-title in 1969, taking on Leotis Martin for the vacant North American Boxing Federation crown. Liston was flattened in the ninth round by a vicious right, but not before landing a fourth-round blow that detached Martin’s retina and prevented him from ever fighting again.

Liston’s final fight was in Jersey City, New Jersey, on June 29, 1970, a nine-round win over Chuck Wepner. Six months later, living in Las Vegas and reportedly in debt, running with a crowd of gamblers and drug dealers, he died at home. His wife, Geraldine, discovered his already-decomposing body six days later when she returned from a holiday trip, in bed and with a syringe nearby. The coroner found evidence of heroin in his system and said the cause was drug-related heart failure. Geraldine believed he was murdered and in 1989 the sordid episode was featured on the TV show “Unsolved Mysteries.”

Author Paul Gallender is among those who think Liston never got his due.

Liston was one of 25 children of an Arkansas sharecropper who beat him. He had no birth certificate and no education but learned to box while in a Missouri prison after being arrested following a series of robberies and muggings. His arrest record found its way into almost every news story about him.

“There was a persona that had been largely created I believe by both the police who ran him out of every town and the press that he was a mobbed-up fighter, as were all fighters back then,” said Gallender, who wrote “Sonny Liston: The Real Story Behind the Ali-Liston Fights” in 2012. “The press never really gave him a chance. And Sonny really was a man of few words. He could tell they didn’t like him and they were being disrespectful to him. And they decided this guy was beyond redemption and was just a bad guy.”

Gallender’s research leads him to believe that Liston was probably in his mid-40s by the time he fought Ali. His age was listed at 30, 31 or 33 before the Lewiston fight, depending on which day’s paper you picked up.

Gallender is among many who think Liston took Ali lightly in their first meeting, believing that the upstart wouldn’t be able to last more than two rounds. For the anticipated rematch in November 1964, a bitter Liston trimmed down from 218 pounds to 212 and was primed to reclaim his title. The postponement, Gallender said, “was the saddest day of Sonny’s life.”

With six more months on his hands, Liston resumed his heavy drinking. He weighed in at 215¼ on the afternoon of May 25, 1965.

“He had a mean streak. He had a dark side,” Gallender acknowledged. “But anybody who knew him loved him. Everybody said he was basically a gentle man. What’s patently unfair about the whole thing is that Sonny Liston’s legacy and career and what people think about him as a fighter is based almost entirely on those two fights with Ali. Why isn’t Ali’s career defined solely on his dismal performance against Leon Spinks (a 1978 loss)?”

Bentt, the 50-year-old who won the World Boxing Organization heavyweight title when he knocked out Tommy Morrison in the first round in 1993, studied Liston extensively before portraying him in Michael Mann’s “Ali.” Bentt’s father also was illiterate, and that informed how he viewed Liston.

“He’s a man who is virile and imposing, but he’s lost. He can’t really articulate what he’s feeling,” Bentt said. “When I was younger, I would see the same look in my father’s eyes.

“It’s all protection, isn’t it? If I’m a black man in 1950s, ’60s America and I can’t read or write, all I’ve seen is violence, I don’t believe in myself. So I have to use the tools that are available to me, and that’s my fists.”

For Bentt, the story of how Liston found his mother says it all. At age 13, Liston either took a bus (or walked, in some accounts) from Pine Bluff, Arkansas, to St. Louis to reunite with Helen Baskin, who had left his father and taken some of his siblings along.

“That showed me how much he was in search of this thing that we call love,” Bentt said. “Sonny was fierce and brutal, but it was all exterior nonsense. He was abused by his dad and did time in the joint. How does that form you?”

Gallender’s book, and a 2008 movie called “Phantom Punch” starring Ving Rhames as Liston, are among recent attempts to resurrect and correct his story, not as a career criminal who happened to be a good boxer, but as an embodiment of the American spirit and a self-made man.

Ezra points out that former heavyweight champion Mike Tyson is a convicted rapist and that current boxing star Floyd Mayweather has been accused of violence against five different women, both far beyond anything Liston did.

“I think boxing is kind of like the receptacle for everything tainted about society, where people’s darkest fears get celebrated,” Ezra said. “Nowadays, Liston would be seen as a rehabilitated character who proves the American society works. The racism was too strong back then.

“Liston never assaulted women. Liston got in fights with other bad men. He would be seen as someone who represented the working-class values. I think you’re going to see several books coming out about Sonny Liston over the next few years. I think as the generation that saw Liston when he was great reach their twilight, they’re going to want to speak on that subject.”

• • • • •

With the benefit of 50 years of hindsight, it’s easy to see the outcome of the Lewiston fight as preordained. That Ali would become an international icon such as we’ve never seen, while Liston would die alone under sordid circumstances.

The reason the fight is still remembered at all is because of who ended up winning.

“We probably wouldn’t even be sitting here talking about this if Ali didn’t become who he was,” said Valenti, who was a 14-year-old the night of the fight hawking programs for his uncle to the closed-circuit crowd at the Lowell Auditorium in Massachusetts. “The legacy really is that picture of him standing over Liston looking down at him. It became the picture that defined that era. None of the stuff with Liston matters, who he was involved with and how his demise came to be. It’s more about Ali and what he represented, who he became and what he meant to a lot of people.”

This is the popular view, forged by the memories of legions of Ali admirers. No athlete has ever cast a larger shadow.

Liston, the wearer of the black trunks that night, played the part of the unwitting foil.

But was there another possible outcome?

Not to some.

“The bottom line here is that Liston loses to Ali 100 times out of 100,” asserted Russo, who has staged 100 boxing events in Portland alone.

Hauser, one of Ali’s numerous biographers, is equally blunt: “No one up (in Maine) wants to hear this, but if you took away the second Ali-Liston fight, if it simply had been canceled, I don’t think the Ali legend would have evolved rather differently.”

Still, the day before the fight, Ali seemed to express some doubt, in a rare downbeat media session.

“Whatever happens, I have plans about what I’m going to do. Something I like better than boxing. To me, boxing is a strangers’ game. An easy way to make money, sure. But I have another mission in life,” said the man already calling himself “The Greatest.”

“If I lose, I may as well retire, because I’d never get another shot at the title. I know the majority of people – the press and the fans – want to see me get beat. I can feel it when I talk to them. They want to see how I’ll look on the canvas.”

As for Liston, he knew he could never match Ali’s charisma, nor his bravado.

But he tried, casually offering a prediction that seems perversely prescient now.

“Don’t blink,” he warned Maine boxing fans. “If you do, you may miss the knockout.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.